Richard Nixon resigned nearly a decade before I was born. But the impact of investigative journalism that helped take down a president still reverberated when I was in high school.

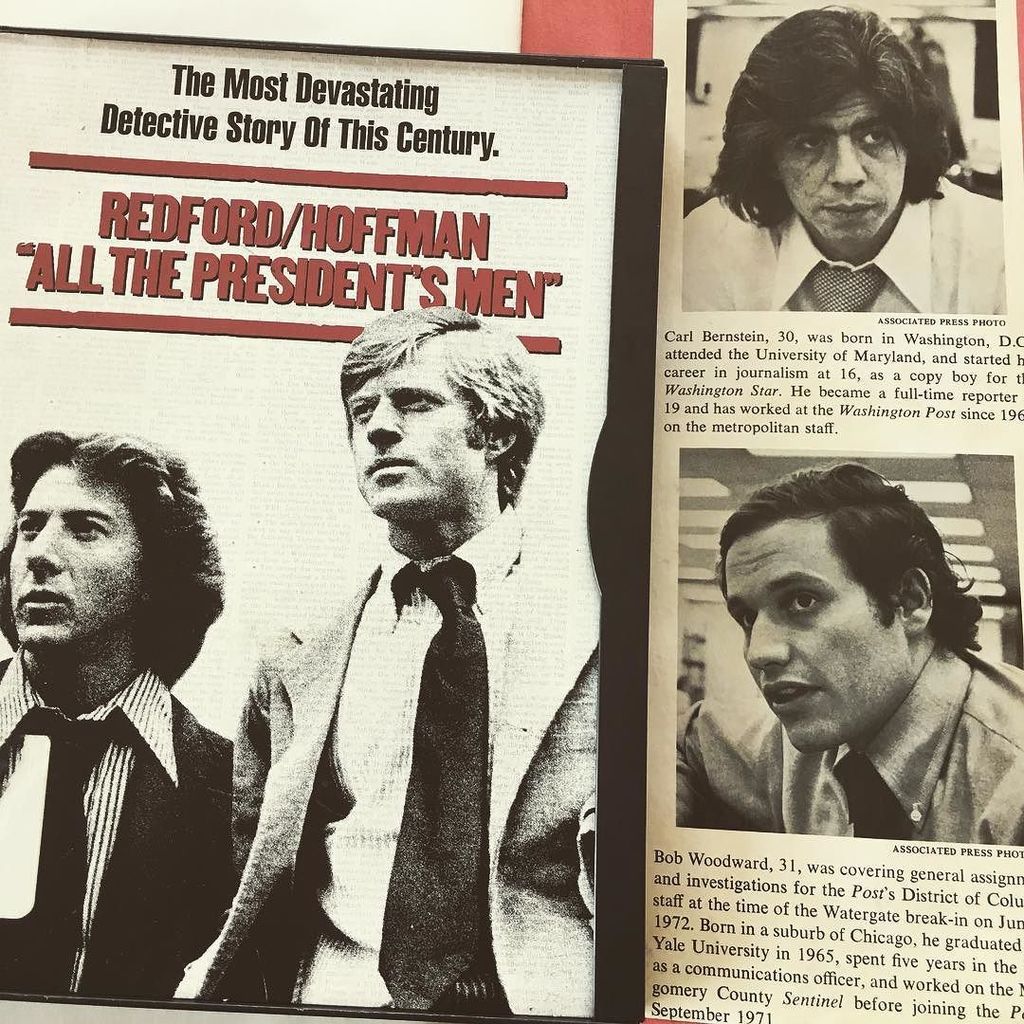

After learning about “All the President’s Men” in history class, I checked the movie out from the library and watched it over the weekend on top of doing my homework. The Hollywood-ready script of crusading Washington Post reporters is partially what inspired me to study journalism in college. Writing and reporting, I felt, was one way I could make a difference.

I certainly wasn’t the first journalism major to feel this way.

Writing in the Washington Post in 2012, Leonard Downie Jr. explained how Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein inspired generations of young journalists to become investigative reporters.

For journalism, their Watergate stories and “All the President’s Men” (the book and the movie) have had an enduring impact,” Downie said.

There’s the key word: Impact.

It’s impossible to deny the impact of Woodward and Berstein’s investigative reporting, which helped lead to the only resignation of a U.S. president. Impact as a media metric is something we write a lot about at MediaShift. To name a few recent examples:

- Futures Lab #187: Community Impact Newspaper (March 27)

- Dealing a Deck to Explore Media Impact and Engagement (March 14)

- MetricShift Survey: Audience Engagement, Impact Measurement Are Top Priorities (Feb 6)

Our MetricShift Facebook group is called Metrics & Impact.

“Scratch a journalist and you’ll usually find an idealist,” Gwen Ifill said in 2010. As writers, reporters and journalists, we all want to make a difference. We all want to see our work matter.

But recently, I’ve become more cautious and conflicted about the idea of impact and the media. It’s because I started reading “All the President’s Men.”

Revisiting an iconic story

I wanted to revisit the story that helped shape me as I teach a new generation of students, so I checked out a copy of “All the President’s Men” from the university library. The pages are yellowed, dog-eared and filled with penciled notes in the margins from decades of students checking this book out for assignments.

I don’t know what I expected to learn 20 years after I watched the movie. But I was surprised at the theme that keeps jumping out at me again and again: Don’t get too caught up in your impact.

The book doesn’t gloss over the missteps that Woodward and Bernstein made along the way in their reporting. There were plenty of mistakes.

Sometimes, their belief in the cause of their reporting led them to do unethical things. At one point, Bernstein retrieves call records from a source at the phone company, a.k.a. spying. To do this, he pushes down his own misgivings:

“It was a problem he never resolved in his mind. Why, as a reporter, was he entitled to have access to personal and financial records when such disclosures would outrage him if he were subjected to a similar inquiry by investigators? Without dwelling on his problem, Bernstein called a telephone company source and asked for a list of (a Watergate burglar’s) calls.”

In addition, Bernstein purposely concealed his identity as a reporter to get a call back, and once (briefly) impersonated someone when trying to uncover information. These instances not only overstepped the Post’s ethical lines, they put the investigation on shaky ground.

Another time, the Post was rushing a story to print after they had been scooped by the Los Angeles Times. The reporters were feeling pressure to regain their edge. They named three men in a front page story who turned out to be innocent of any wrongdoing. The stain of the Watergate association impacted the lives and careers of the men implicated by their story.

“Three men had been wronged,” the book recounts. “They had been unfairly accused on the front page of the Washington Post, the hometown paper of their families, neighbors and friends.”

Their worst mistake was when they printed that a source had testified information under a grand jury — which had never happened (even though they were correct about the basic facts of the case). The White House seized this mistake to attack the Post as “malicious,” “elitist,” “hostile,” “shabby journalism,” anti-Nixon and pro-Democrat. (“The Post’s reputation for objectivity and credibility have sunk so low they have almost disappeared… altogether,” Nixon surrogate Bob Dole said in a 20-minute speech blasting the Post.)

So how did these mistakes happen? Woodward and Bernstein retraced their steps after one major factual error threatened to undermine months of reporting. They came to one conclusion:

“They had heard what they wanted to hear.”

Woodward and Bernstein were getting so close to the prize, they took shortcuts to get there. They were almost giddy with excitement when they thought they had a break in the case against Nixon’s top aide. They assumed too much. In doing so, they almost destroyed their case.

They were consumed by Watergate reporting, working extremely long hours, sleeping in the office and (in Woodward’s case) famously meeting with Deep Throat in a parking garage in the middle of the night.

But when you get too focused on the end goal, it’s easy to lose perspective.

Avoid ends-justify-the-means thinking

If Woodward and Bernstein wanted a cautionary tale of getting too caught up in the mission, they didn’t have to look far.

They learned that Nixon’s campaign viewed the president’s re-election as a “holy war.” They were willing to go to any lengths to accomplish their task.

The young, idealistic defector from the campaign that supplied Woodward and Bernstein important inside information didn’t believe in the methods of his colleagues. Here’s how he was described in the book:

“He and his wife believed in the same things they had before they came to Washington. Many of their friends at the White House did, too, but those people had made a decision that you could still believe in the same things and yet adapt yourself. After all, the goals were unchanged, you were still working for what you believed in, right? People in the White House believed they were entitled to do things differently, to suspend the rules, because they were fulfilling a mission; that was the only important thing, the mission. It was easy to lose perspective, Sloan said. He had seen it happen.”

Taken to the extreme, the ends-justify-the-means mentality of a mission can lead to unethical or even illegal acts, as it did with Watergate.

But even if it’s not so extreme, getting consumed by the impact of your project can distract attention away from mundane but crucial details like triple-checking your facts and questioning your assumptions.

Fortunately for Woodward and Bernstein and history, they recovered from their mistake. A sharp rebuke from Deep Throat helped.

Just before I sat down to write this article, I saw this quote posted as a tweet from Matt Pearce, a national reporter at the Los Angeles Times:

anyway, Deep Throat had some timeless advice for investigative reporters: pic.twitter.com/vijaO5Um3l

— Matt Pearce (@mattdpearce) March 30, 2017

The impact is still felt today.

Tim Cigelske (@cigelske) is the Associate Editor of MetricShift. He has reported and written for the Associated Press, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Budget Travel, Adventure Cyclist and more. Today, he is the Director of Social Media at Marquette University as well as an adjunct professor teaching media writing and social media analytics.