Click the image for the full series. (Image courtesy of Flickr user Brett Jordan and used here under Creative Commons.)

It’s always so simple in my head. When I signed up to teach Experimental Journalism at West Virginia University’s J-School last year, I had a clear vision of what I wanted to impart, a schedule of rockstar speakers from the industry and an ambitious plan to bring a touch of anarchy to a group of students. The gap between fantasy and non-fiction is very wide, however. What is the line in Spinal Tap? “There’s a fine line between clever and stupid…”

It was, of course, more challenging than I could imagine. Teaching and working full time is killer; doing so at a distance is tricky even when leaning hard on Google Hangouts. And to my surprise, when I visited campus and students were graced with my actual presence, they didn’t suddenly snap to attention. Until I yelled at them.

Last but not least, there was the matter of the boutique hotel decorated like a Persian brothel with faulty windows that let a rainstorm into my room one night at 2 a.m. OK, that has nothing to do with the class directly. But I can complain.

On the upside, I had the full backing of the faculty, which was critical, including John Temple, Dana Coester and Elaine McMillion — my co-teachers. They were crucial in helping me rein in the chaos and overall the class was successful in setting up a framework for WVU’s Innovation Center. That is an excellent outcome.

Lessons Learned

In hindsight what lessons did I walk away with? Here are three:

Lesson 1: Being a student does not equal being open to experimentation.

In theory, I thought because I was working with students, not cranky professionals with ingrained work habits, the kids would be open to experimentation. Our project was pitched as a “data-driven device-centric story-form agnostic multimedia project.” We were building a non-traditional story — working around data, audio, video, photos and then words. In my head, everyone would want to get their hands dirty with something new.

In practice, regardless of age, most of us like the feeling of competency that comes along with doing something we know we’re good at. So being a college student doesn’t translate into wanting to pick up a video camera when you’re not comfortable shooting moving images or working with data when you have an aversion to numbers. Some students were open to stretching, some had to be pushed to try, and most defaulted to building on what they already knew.

Lesson 2: Not everyone is going to love working with data.

The project was data-driven and I very much wanted the data to be something the class could relate to. My hope was to turn them on to data journalism. To that end, we created our own survey (on drug use and ADHD drugs on campus), distributed it, collected the data and used the results to drive our reporting. When the data came in, however, the usual resistance to the abstraction of numbers arose. We had multiple questions, multiple answers and a massive spreadsheet. Two of my students who already had an interest in data visualization took ownership of grooming the results and finding meaning.

Again, back to human nature. There is only a small percentage of us in any room at any given time who have grey matter predisposed to wrangling data. Just because we can now track our daily runs or obsess over the number of Twitters followers doesn’t mean everyone is attracted to the care and feeding of data, or capable of wrestling it to the ground.

Lesson 3: Turn your liabilities into assets.

A project on illicit drug use on campus isn’t, by nature, particularly visual. From the start we were worried about how to visually represent our story. We did the expected: We shot the campus doctor, we shot the campus and found some students who were willing to be on camera but that was because they were talking about how they didn’t use the drugs. The international students found even the concept of ADHD foreign. So we didn’t have stunning visuals.

What we did have was some amazing audio of kids talking about how they used the drugs. We edited those into a collection of the best stories, created a set of icons and packaged them together. The audio section became some of the most compelling material in the piece.

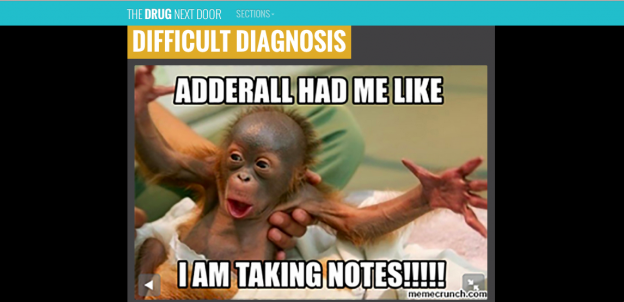

The other thing we had was imagery from the culture around study aid drugs, including memes on the Internet. We used those to open each chapter. Interestingly enough, at first the class was resistant to using the memes, the thought being we were denigrating the material. But the images captured the blasé spirit of the users and pushed our project from representative into immersive. Meaning: I talked them into it.

By the end of the semester in May, our final product — The Drug Next Door — was a success. Great on mobile, where most of our users viewed it, though weaker on desktop. In hindsight, though, I still wonder if we set out to do too much: from the poll, to the data, to the interviews, to the design, to the social push, to the guerrilla marketing. Should we have gone deeper on fewer things instead of wide on so many? That is a lesson I’m still sorting out.

Sarah Slobin — www.sarahslobin.com — is a visual journalist at the Wall Street Journal making data and multimedia stories on the interactive graphics desk. She spent 15 years learning data, reporting and infographics at the New York Times and then three years as graphics director at Fortune & Fortune.com learning to make shiny magazines. She thinks the future of news may well involve dogs.