Like many journalism educators, I spend a significant amount of time in my classes drawing what I hope is an unimpeachable link between journalism at its finest and democracy at its purest.

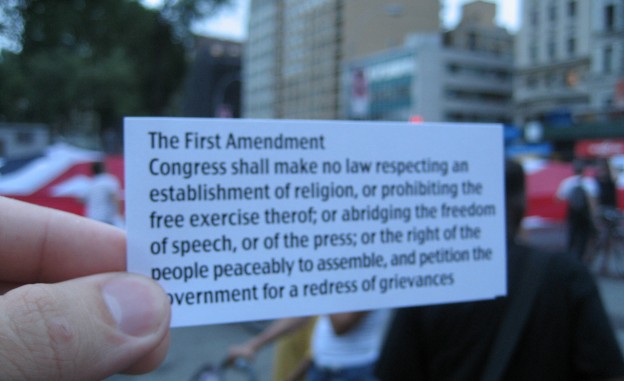

I quote James Madison (in faux Colonial voice, no less), we read Cato’s letters, and my students learn what “watchdog” and the “Fourth Estate” mean. Historical moments such as Watergate and the Pentagon Papers, and more contemporary issues like WikiLeaks and Edward Snowden, are well-worn examples of the intricate relationships between the press, the public and philosophical ideals of democracy and self-government. In short, my students know the drill (bonus points for the ones who can recite the First Amendment from memory).

But also like my colleagues, I’m faced with the reality that education at all levels is shifting. We are trying to compensate for (and also take advantage of) an increasingly digitized and skills-focused classroom experience. In the journalism field specifically, educators must find the time to teach writing, reporting, interviewing, data mining, digital security, and social media, among other 21st century literacies. Who has time to wax poetic about theories of democracy and the information needs of communities when the demands of technology mean our students must reinvent their skill sets every year?

What Will Best Prepare Our Students?

This dilemma plays out even in the assignments I require: I want my students to think deeply, critically and personally about the roles journalism and mass media play in the 21st century. But I also need them to put the commas in the right place and cite sources accurately. If, at the end of the semester, my students can do the former but not the latter, how will they fare after graduation? In a world that will judge our students on their competencies in reading, writing, and technology, how do we justify making time for the most meaningful conversations that can’t be graded on a rubric?

More specifically, as a journalism educator, should I be taking time to meander through some of the greatest theoretical debates in history when the ever-changing demands of digital technology require me to rewrite my syllabi every semester just to keep current?

Most days, I sense that these are not even the right questions but instead reactions to a more pressing, more significant consideration: Given the technological and digital demands on today’s students and tomorrow’s journalists, where is democracy’s place in the modern journalism classroom?

Photo by Paragdgala on Flickr and used here with Creative Commons License.

Before we can begin to understand the answer, let’s be clear about one thing — we’re not talking about a political construction of democracy, but rather a philosophical notion. It’s not just a semantics issue. It’s the difference between the act of voting and the conscientiousness that compels one to do so in the first place.

Bringing democracy into the journalism classroom is not about political parties, donkeys or elephants, red or blue. It’s about exploring the extent to which a society values qualities like equality, opportunity and openness, and if so, what role journalism has in monitoring the mechanisms — both individual and institutional — that support such qualities.

Challenging My Own Beliefs

Earlier this semester, my students read Barbie Zelizer’s “On the shelf life of democracy in journalism scholarship,” an article published in the academic journal Journalism in 2013. Zelizer, a former journalist and now professor at USC’s Annenberg School for Communication, calls for the “retirement of the concept [democracy] as a key term for understanding journalism.”

Zelizer is not the only expert to recently articulate a disenchantment with the centrality of democracy in the case for journalism. Others, like Columbia University professor Michael Schudson in his 2013 article “Reluctant stewards: Journalism in a democratic society,” are concerned more with adopting a journalism/democracy relationship that doesn’t constrain modern journalism, one that “gives play” to and takes advantage of the rather unstable contemporary newsroom.

I chose these articles for my class in part to confront my own deeply held ideologies. A tune-up, if you will. But even after reading, discussing and dissecting their arguments with 30 of my brightest upper-level students, I still remain unconvinced: If journalism is about speaking truth to power, then explorations of democracy cannot be on the periphery in our classrooms.

So, I’m learning to reframe the questions. Instead of asking how journalism supports democracy, or vice versa, we should be asking more pointed questions: Which technologies (and what kind of skilled use of these technologies) are most important for journalism today? What digital competencies bring citizens and journalists together for the common good and highest public service?

Image by Doug Belshaw on Flickr and used here with Creative Commons license.

Little more than a week after a midterm election with the lowest voter turnout in 70 years, perhaps there is no better time for journalism educators to engage students in discussions that might otherwise seem like a luxury. At moments like this in our political process, the most important conversations are undoubtedly about the technologies, the structures, and the philosophies that construct our democracy.

But don’t worry, come January you’ll still find me quoting James Madison to a new cohort of students. Even as journalism education and the industry change, some things will never go out of style.

Megan Fromm, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of communication at Boise State University, where she teaches journalism courses,. She is also the professional support director for the Journalism Education Association and a former journalist and high school journalism teacher. Follow her on Twitter via @megfromm.

Is it really separate though? I love this article and the discussion about what questions we should be asking, but the captions and some of the language here make it seem like teaching digital skills is overtaking space to talk about democracy. I teach skills courses, and feel I would be doing students a disservice if they weren’t also taught to think about how their programs and sites and so on that we create affect communication, who gets to partake and what barriers exist. Not hard to, for example, talk about how a website works and also introduce the idea of the digital divide in the same class session. Sure, you can’t go into depth on one without shorting the other, but it’s about reinforcement. Skills taught as simply skills are, in my opinion, skills taught out of context whether they are technical, writing or otherwise. Connections made from course-to-course and from the skill to the larger societal picture help students be better citizens and critical thinkers.

You’re so right, TheLastUnicorn. And I *hope* it’s never separate. Unfortunately, I do see many instances in which it is. It’s a divide that at some places is more apparent (and real) than at others. I know that at times some of my own colleagues even assume that the skills classes I teach (and love) are not adequately discussing these questions, when indeed I know that they are. I couldn’t have said it better than you did that “skills taught as simply skills are…skills taught out of context.” Amen!