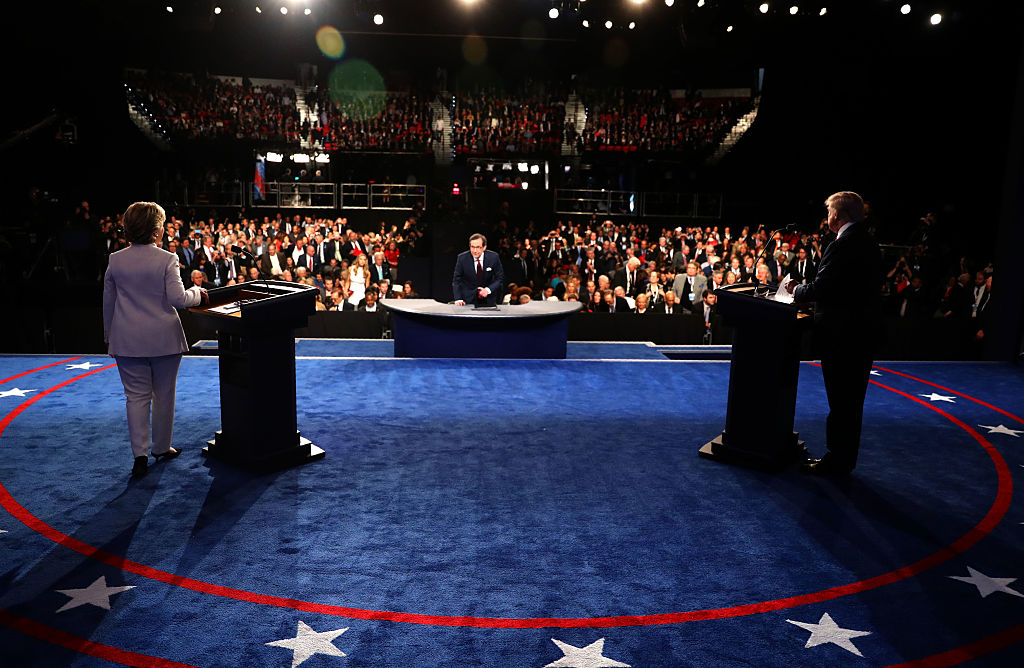

Born of a desire to insert actual facts into the heated debates surrounding the 2016 U.S. presidential election, EconoFact was launched in January 2017.

A project from the Edward R. Murrow Center for a Digital World at the Fletcher School at Tufts University, EconoFact seeks to lay out complex domestic policy issues in an easy-to-read memo-style format. Since its launch, the site has published more than 100 pieces of policy analysis that are designed to be evergreen.

The topics that are covered most often include hot button issues like immigration and trade. But the site covers a variety of issues, including college funding and endowments, explained Edward Schumacher-Matos, the site’s publisher and co-executive editor and a visiting professor at the Fletcher School.

We spoke to Schumacher-Matos to learn more about the site and the difficulties of advocating for facts in an anti-truth era.

Q&A

Tell us about EconoFact and how the project got started.

Edward Schumacher-Matos: I was working on a project called Iceberg, a global online publication that features pieces of analysis by experts in different parts of the world. Michael [Klein, professor at the Fletcher School] came in to see me. He was quite disturbed about the election and the tone that had transpired. In talking with colleagues, they were upset that so many basic facts that they know about economic and social policies were not being discussed or used by either candidate. It was a frustrating experience. Trump in particular had little command or even respect for policy. The Hillary campaign misused facts, but Trump was the bigger violator. So we tried to figure out what to do.

With social media you can have your own voice – it’s just a matter of how you organize it and go about trying to promote it. We thought, great, we can do something by launching a site that explains domestic policy. But is this just another site for opinion of which there’s so much? How can we distinguish this and make it different?

I teach opinion writing. When you are trying to argue a point of view, you should be explanatory and put the facts first. There’s this idea of structured journalism that we’ve been playing around with. Could you build a common body of stories that includes all the facts, and each new fact is just a short update? And then you’d link it back to the base. You can break the story into facts and do that as long as we all agree on that common base of knowledge. None of us has been able to make that work. The New York Times, the BBC and Reuters have played around with this. Academic institutions have also tried to do it, but it hasn’t worked. But this is what inspired us, because it forces the facts to be first and the information is delivered in a memo style.

How do you choose the topics you cover?

Schumacher-Matos: We have a weekly editorial meeting. We have an editor, Miriam Wasserman, who works out of Ann Arbor, Michigan. She’s a Fletcher grad. She worked at the Boston Federal Reserve Bank as an editor of their magazine and has held other jobs in journalism. Michael is the executive editor. He’s the real inspiration and editorial leader. I’m more like the publisher. Michael put together the network of economists. On Monday mornings we talk and look at what’s in the news and what we think is going to be in the news.

Edward Schumacher-Matos

Do you go back and update older memos?

Schumacher-Matos: We haven’t had to. But yes, we will, if f it requires updating. In the future we’ll probably have to do more of that.

Who is your target audience?

Schumacher-Matos: Influencers, journalists and policymakers. If we had the money, we would try to break out and try to have a social media engagement strategy. But in the meantime we keep growing organically.

We want to get to what we describe as “an NPR audience” – an informed public audience. NPR’s audience is half Democrats and half Republicans. We do not want to be pigeonholed with just one political tribe – we really want to appeal to all sides and bring down the tone of the debate and talk about the facts. When you’re looking at a problem, what are some of the logical, rational ways of solving it? There may be more than one way, but let’s at least agree on the facts first.

What are some of the challenges in running the project?

Schumacher-Matos: Our biggest challenge is to keep trying to grow the audience. We’re convinced the editorial formula is excellent, and we see the response we get from people when they come into contact with us. Everybody gets it. Everybody’s tired of all the extreme opinions and the shouting. We don’t really have to explain what we’re trying to do.

How do you vet the economists that you work with?

Schumacher-Matos: Michael’s the guy who does that. We want the economists to feel some attachment, some loyalty to the project. I think we’ve done that. Clearly, we can’t pay them. I wish we could. If we had the money we could. We’re trying to raise money.

A graphic from a recent EconoFact story about high school students having trouble attending colleges that are further away.

What kind of impact do you hope to have, and how do you measure that?

Schumacher-Matos: We’re getting picked up more and more by the news media. We’re getting quoted more. That’s growing. You begin seeing who’s seeing it. We’re quoted on the radio a lot too. It’s hard to measure how you are affecting policy. That’s a longer-term measure. We just have to keep at it. We think we are having an impact. We see people in Congress reaching out to us and following up if they want more information. They talk to the economists. We want to reach out more to state governments and regionalmedia as a way to provide information at that level. There’s a lot of information available in New York and Washington, but what about the rest of the country? We also try to make the memos as accessible and readable as possible, so you don’t have to be an expert to understand them.

How do you deal with the issue of trust in a time when so many people are so anti-fact? There are people who think that if something is coming from a news organization or a university, it can’t be trusted. How do you address that?

Schumacher-Matos: We deal with it through our tone and how we write. We allow zero demonizing or criticising of other groups and other points of view. We try to have a very sober, clear and open tone that we hope strikes an empathetic chord that reaches everyone, no matter what your point of view might be. And we do not telegraph that we’re part of one tribe trying to do battle with another tribe. We try to stay away from that. That’s part of the structured memo format and the “facts first” thing. You’ll see no critical adjectives about somebody else or about political leaders. We focus on the facts, not on political fighting or trying to score points.

What are your future plans?

Schumacher-Matos: In addition to looking at publishing and distribution partnerships, finding ways to grow our audience. We need funding to allow us to do that. So far we’ve done very well organically. And we’re looking again at the original Iceberg project. EconoFact focuses on domestic issues, but maybe we can take some of those pieces and repurpose them internationally. Some of them won’t be appropriate but some of them well.

Bianca Fortis is the associate editor at MediaShift, a founding member of the Transborder Media storytelling collective and a social media consultant. Follow her on Twitter @biancafortis.