One of the most prolific organizations taking on “fake news” is the First Draft Coalition, a network of more than 100 news organizations, platforms and technologists that provides “practical and ethical guidance in how to find, verify and publish content sourced from the social web.”

The two-year-old non-profit’s initiatives include CrossCheck, a collaborative online fact-checking effort focusing on the French Election, visual verification guides like NewsCheck, a Chrome extension that can verify the authenticity of an online image or video as well as events such as MisinfoCon, a multidisciplinary summit on misinformation that took place in Boston last month.

I spoke with First Draft’s research director Claire Wardle about major hurdles in the fight against fake news, how peer-to-peer networks can help and why she intends to enlist librarians in the fight against misinformation.

Q&A

MediaShift: How would you describe the current state of the fight against misinformation?

Claire Wardle: Fractured. Technology companies are acknowledging the seriousness of the problem, are taking steps, such as cutting off some of the revenue opportunities for people creating fabricated new sites. Traditional media outlets are grappling with their role in an ecosystem where trust in their work is incredibly low. Technologists want to help but are unsure what is exactly needed by platforms and publishers. Research on the subject is happening in many disciplines, but those are siloed conversations. Ultimately, the challenge is complex; Factors driving these trends have been developing over many years, and if we’re serious about solving the problems we’re facing, we need to acknowledge it is going to take time, and will require all elements of the information ecosystem to take a critical look at their own role in where we find ourselves today.

What are the biggest challenges?

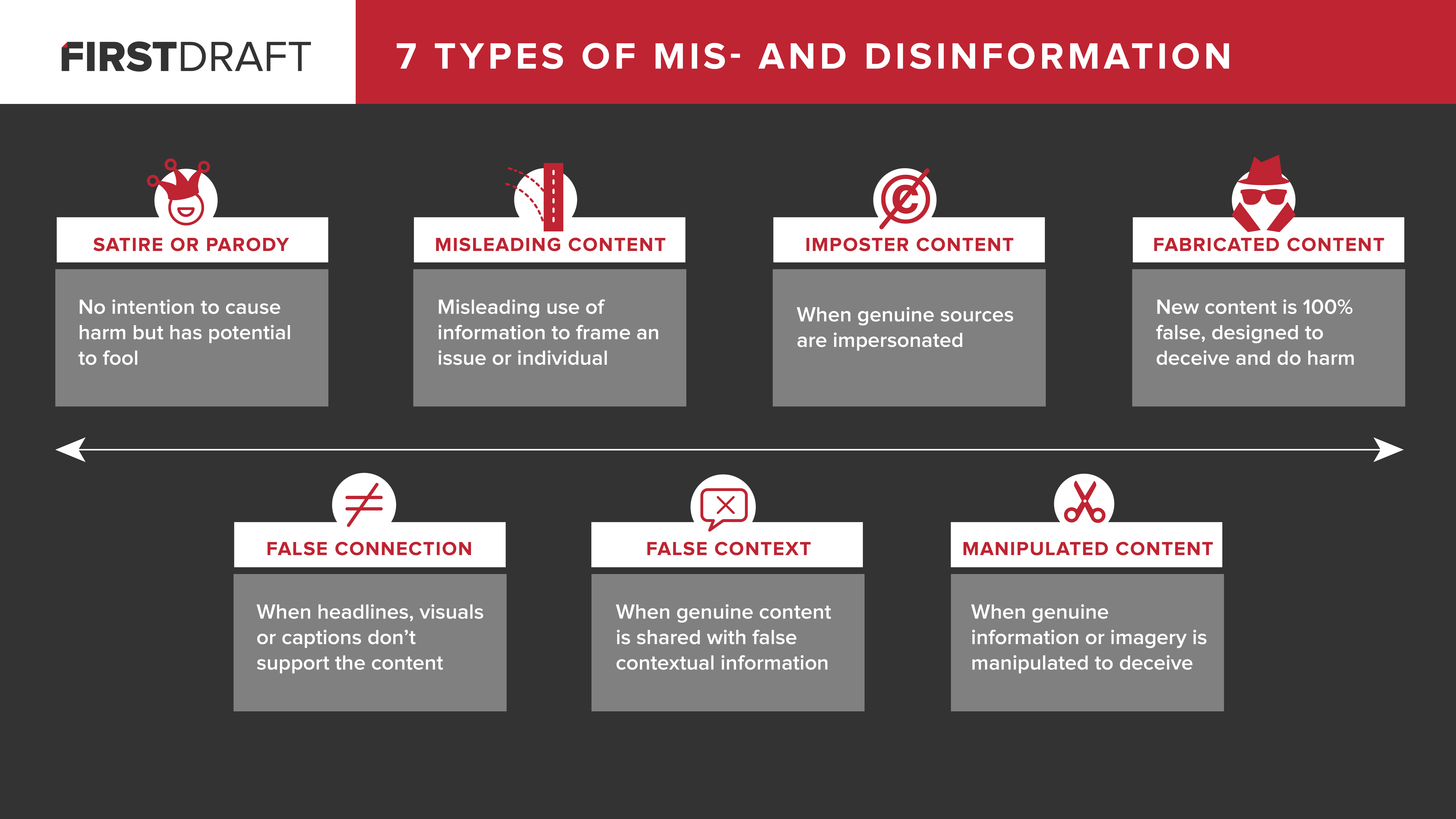

Wardle: The complexity of the issue, and the fact that any solution requires collaboration from organizations that have traditionally been competitive. There are many reasons mis- and disinformation exists – examples are profit, partisanship or propaganda. And there are many types of mis- and disinformation, for example when ‘correct’ but old images recirculate during a breaking news event, or automated bots pumping out memes in an attempt to impact opinions towards a candidate in an election. When I hear people say ‘how do we solve the fake news crisis,’ I want to throw my hands up in frustration.

In an article for GlobalVoices, Ivan Sigal argues that instead of tinkering with the effects of systemic social challenges like fake news, we need to start a serious conversations about them. Do you agree?

Wardle: I completely agree with Ivan. This ‘crisis’ has been a long time coming. And while in the US it feels new, that is certainly not the case, and only by studying this at a global level, does the scale of this issue as well as its complexity become even clearer. What we’re seeing is the result of many different factors, including as Ivan says, a number of systemic social challenges.

How much responsibility do Facebook and Google have in the fight against misinformation, and do you think governments fining them will be helpful?

Wardle: When we think about misinformation, we have to think about three ‘buckets’. 1) What is driving people to create this type of content? 2) What types of content are being created? 3) How is this content being disseminated? Both social platforms have made it clear that they are attempting to tackle the problem, whether that’s stopping creators making money (see point 1) or giving people more information on the platform via the pop-up ‘this link has been disputed’ on Facebook or the ‘fact-check’ tag on Google News (see point 3). There is more both can do, though. While threats of regulation and fines from European governments will likely push them to move faster, I have significant concerns about what these pieces of legislation might do.

Why do you think some people seem to be fact-resistant? Is it possible that they see fact-checking as a(nother) way of imposing an opinion on them?

Wardle: There is a huge literature from social psychology that explains why people are not seeking out facts, including recent work by Brendan Nyhan, Emily Thorsen and Lisa Fazio. I have real concerns that as a news industry, we are ahistorical and atheoretical, and I’m seeing ideas and solutions that have not been tested, and actually go against accepted wisdom about best practices for battling misinformation.

You said tackling the ‘fake news’ problem will take time. Are there any promising solutions that can be implemented quickly?

Wardle: We shouldn’t be implementing anything quickly. Instead, we should be testing potential solutions, both in experimental labs as well as in the field. If we implement new flags on Facebook, what does that do in terms of sharing or in terms of how people make sense of information? Do collaborative journalism projects lead to greater levels of trust from audiences? How does the way we word fact-checks impact audiences? Are we causing more harm? How effective are news literacy programs? We have a lot that needs to be researched, and that is what we should be prioritizing.

Do you see journalism business models fueling the misinformation ecosystem? If so, do you have a suggestion on what can be done to address this deficit?

Wardle: Yes, the news industry is part of the problem, both in terms of disseminating information that is misleading and sometimes downright false. Examples are identifying the wrong suspects after events, sharing old footage during breaking news stories or using clickbait headlines. Newsrooms are struggling, and are being squeezed. There are fewer resources for verification and fact-checking, and newsrooms are operating in a highly competitive space. We already know newsrooms have to think more creatively as an industry and there are serious questions about whether ‘scale’ on the internet is sustainable. With trust levels as low as they are, it suggests newsrooms are going to think and act differently to re-build those trust levels. The sprawling, duplicative industry that we have now cannot continue, both because of financial constraints but also because audiences are not being served in ways that they want.

According to a recent study by the Media Insight Project, “people make little distinction between known and unknown (even made-up) sources when it comes to trusting and sharing news.” What lessons do you draw from the study that could be applied to the fight against misinformation?

Wardle: This study shouldn’t surprise us. Our brains are overwhelmed by information every single day. We’re consuming more information than ever before. We are therefore more reliant than ever on heuristics, i.e. mental shortcuts. The fact that your friend, who you trust, has shared information, is an incredibly powerful shortcut. Our brains are lazy, and when it doesn’t have to kick in critical thinking, it won’t. Peer-to-peer networks are a secret [weapon] in the fight against misinformation. We need to hold each other to account when we share misinformation, and newsrooms need to activate their audiences to share their content, which has been professionally sourced and fact-checked.

How do you see the fight against misinformation play out in 2017 and beyond?

Wardle: There will be no magic bullet to solve misinformation, rather we see it as a collaborative effort that will require every group we’ve connected with via our at First Draft partner network: news organizations, journalists, social platforms, technologists, human rights organizations and researchers. We would also like to add librarians into our cohort as they’ve taught news literacy skills since the web began and have the public trust.

Benjamin Bathke is an entrepreneurial freelance journalist covering media innovation, startups and intractable global issues for Germany’s international broadcaster Deutsche Welle, as well as several other international publications. In 2015-16, Ben was a Global Journalism Fellow at the Munk School of Global Affairs and a multimedia storyteller for Washington University in St. Louis. You can follow the 2017 Reynolds Fellow on Twitter and see more of his work here.