A few days before the election, I got an email from my sister:

“I really feel that if Trump wins this election, the media will be to blame,” it read, in part.

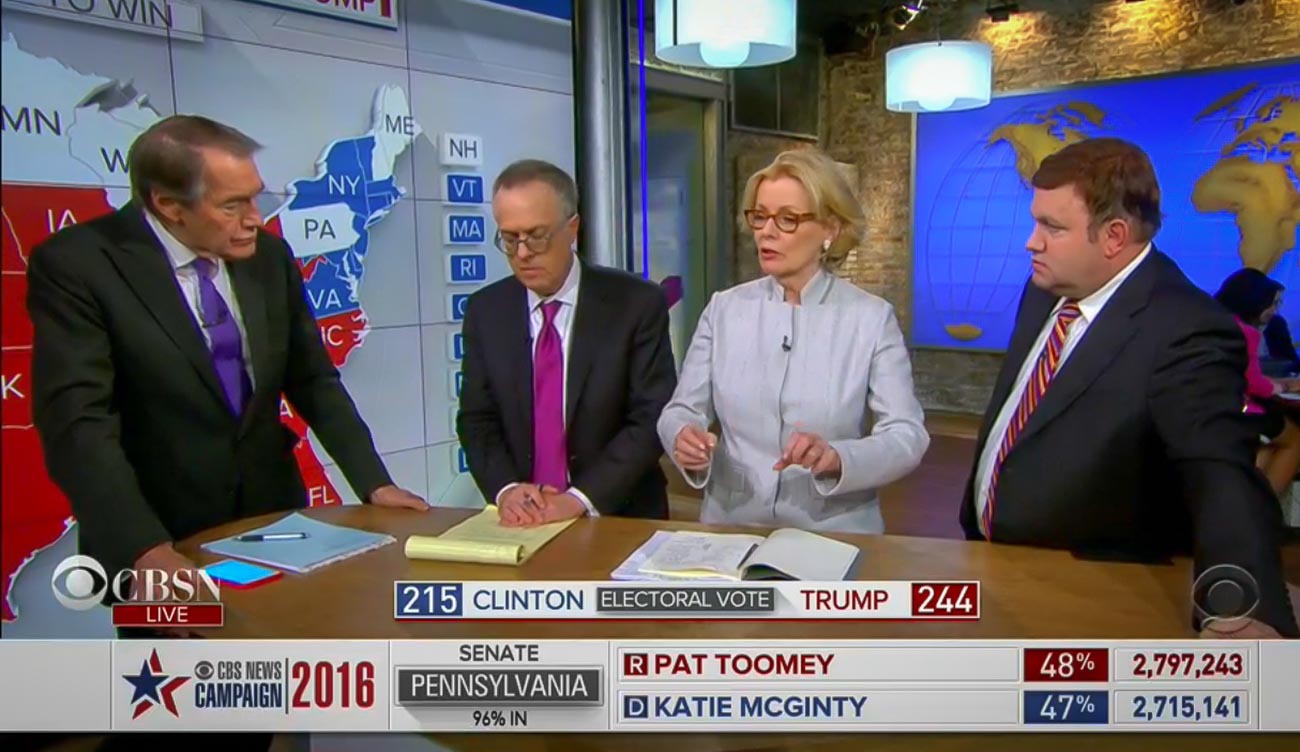

On election night, we watched even the best national anchors and analysts stammering in shock, trying to hide their surprise and horror at the results my sister seemed to spookily predict.

Not only did our nation’s newspapers, broadcast and online outlets severely misjudge what the results would be, the vote seemed to be a direct rebuke to our industry.

Voters defied newspaper endorsements, which leaned more heavily for one candidate than ever before in U.S. election history. And in doing so, they supported a candidate who made vilifying the media a central message of his campaign.

If there’s one thing our country can agree upon, it is disdain and distrust of “the media.” The sentiments of my sister — a highly educated scientist who’s probably never voted Republican in her life — are shared in one way or another by Trump’s lower middle class supporters: “The media is the problem.”

Where did we go wrong? How did a profession made up mostly of thoughtful, responsible, well-intentioned, (add “chronically underpaid” if you like) people alienate so much of the country?

This is a huge question, but we can’t hide from this truth anymore. It’s time to start looking for answers. Here are a few thoughts about how to win our audiences back:

Meet audiences where they are

The immediate narrative coming out of the election was that bicoastal media elite misread the electorate because they didn’t ever really talk to them. That may be true to some extent, but why? Because they’re lazy? No. Because our industry has been gutted.

Those who complain about the media are probably imagining cable news, partisan sites that thrive on social media, or at best the few national newspapers that have been able to survive the contractions of the last decade.

These national outlets are, almost by definition, out of touch with local audiences. But the local newspaper where readers might have known and trusted a columnist or editorial board is long gone.

Advertising and investor funded sites tend to go for the low hanging fruit when it comes to clicks: national stories that are spun to appeal to partisan outrage and fear. There’s simply not much room to connect with an audience or build trust there. The journalists producing the work don’t get a chance to rub shoulders with their audiences, and often don’t reflect their values, not to mention their demographics.

Tell the truth

Don’t get it twisted. By meeting audiences where they are, I’m not saying we should tell them exactly they want to hear. Day-to-day analytics might suggest that readers want factually specious content that confirms their biases. But the big picture tells a different story.

People have an underlying need for good information from sources they can trust. There’s a way to meet audiences where they are, not talk down to them, and still speak to them with a voice they can relate to. Readers might not care for our posturing as objective, omniscient arbiters of truth. But facts, fairness and smart analysis are always going to have an appeal.

Build grassroots publications at the community level

How do we possibly reinvent our industry with this in mind? Start small. Cover your community. Give them a voice. Make them the core of your mission. Build trust. Repeat.

It’s not so far fetched. Seattle’s media landscape is bubbling with such projects. Some have been around for a while; others are brand new. The Seattle Globalist has a training and mentorship model that draws directly from the communities we cover.

Our contributors have the trust and support of those communities, and while they might not always agree on every issue, they’d never be accused of being “out of touch.”

Ask our audiences to pay for good work

Photo by Bogdan Zaharie on Flickr and used here with Creative Commons license.

So how do we fund that? I’ve been in journalism for more than 10 years, and for that entire time we’ve been looking for a magic bullet to solve our funding crisis. It’s time to give audiences a chance to solve the problem for us.

Information is as essential to a functioning democracy as electricity is to a functioning city. If electricity were free, but service was plagued by shorts and blackouts, wouldn’t you be happy to pay a little something for a better provider?

Regardless of how we journalists like to see ourselves, our customer satisfaction is abysmal. We need to rebuild and give our audiences the opportunity to pay for good work — from sources that they can recognize as reflecting themselves and their values.

At the Seattle Globalist, we’ve spent four years of cobbling together dollars from multiple funding sources for non-profit journalism. But now we’re facing an existential budget crunch, so we’re pulling back the curtain and directly appealing to readers to pay the true cost of our work.

Our best shot is to give our community the chance to take “the media” into their own hands and learn to believe in it again.