As more and more journalism programs add courses on media entrepreneurship, just what are students being taught?

As it turns out, many different things. There is not much of a standardized media-entrepreneurship curriculum at journalism schools around the country, according to a recent survey of journalism educators conducted for CUNY’s Tow-Knight Center for Entrepreneurial Journalism. Educators’ definitions of what media entrepreneurship means and what they want their students to learn vary greatly.

The largest cluster of our 85 respondents framed media entrepreneurship around the needs of journalists: Forty-one percent said they wanted to help students go into business for themselves, make money doing journalism, or launch a venture that will bring in enough revenue to be sustainable.

Only a handful of respondents, 20 percent, or 17 out of 85, focused on the audience, aligning media entrepreneurship with Harvard professor Clay Christensen’s definition of disruptive innovation: identifying a job that people need to have done – and then building the solution or being of service to that audience.

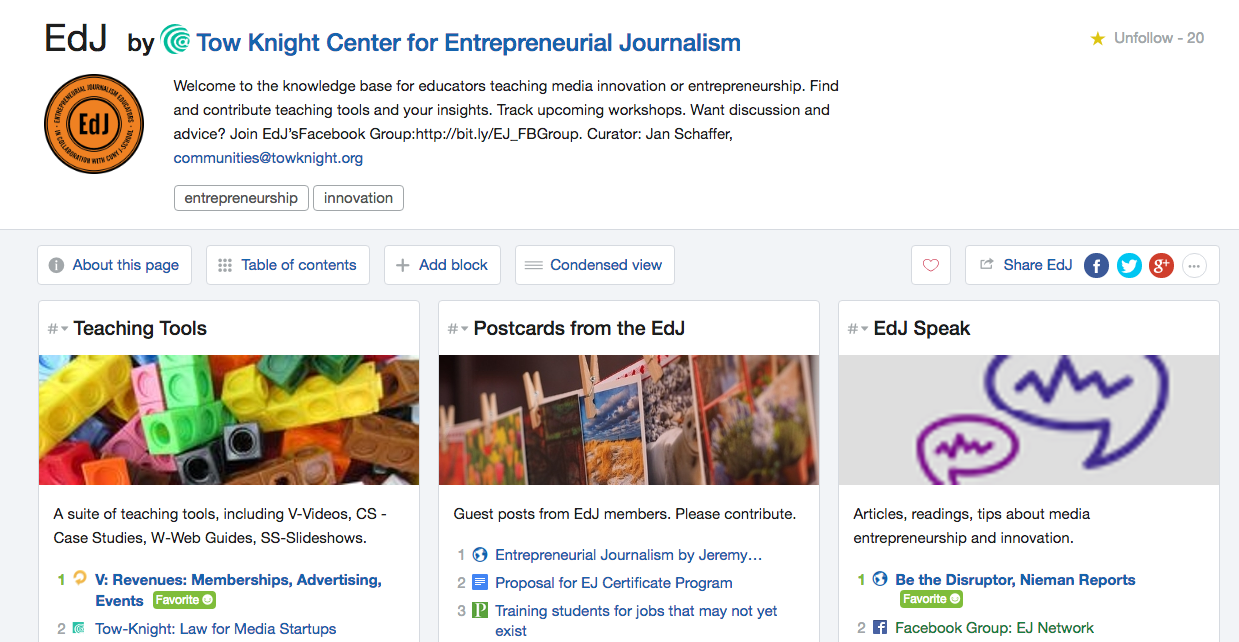

The survey was conducted as part of an initiative to organize EdJ, a community of practice for educators teaching media innovation and entrepreneurship. Some 800 members now belong to the community’s Facebook group. The Tow-Knight Center is spearheading the effort to engage these educators with dialogue, resources, teaching tools and a training summit. The summit is being held July 15 in New York City. This year’s theme is Journalism as Listening – to your audience, of course.

Defining Media Entrepreneurship

When asked to define what “media entrepreneurship” meant to them and what they’d like their students to learn, educator responses ranged from:

• Entrepreneurship means starting an operation that can be monetized.

• Entrepreneurship means going into business for oneself.

• Figuring out how to pay for journalism that matters.

• Any compensated work in the news field that is not tied to a job or salary.

• Using all tools available to tell stories.

• Learning how to think like a businessperson while also thinking as a journalist.

• The ability to plan a digital news/info startup and develop a sustainable business model.

In several cases, educators wanted to help students build businesses as individual freelancers. One described media entrepreneurship as “journalists coming up with stories that are multimedia-oriented and then freelancing them out.” Ten of the 85 respondents said they wanted to help students be their own boss. One of these wanted to help students “shift their perspective from workers for hire to owning equity in what they produce.” In other instances, media entrepreneurship was defined as “any compensated work in the news field that is not tied to a job or salary.”

Some 29 percent of the respondents framed media entrepreneurship as a process of building a new app, product or tool with an accompanying business plan.

“In my case … media entrepreneurship revolves around creating a tech/software product and the consideration of launching a startup, primarily grouped in three areas: Desirability (is this what people want?); Feasibility (can you actually build/deliver it?) and Sustainability (How will you get it launched and keep it going?),” said one respondent.

Many of the educators correlated teaching media entrepreneurship with teaching business skills, often a missing element in journalism programs. Nearly 40 percent, 33 of the 85, saw media entrepreneurship courses or classes as a gateway to help their students learn about business models, revenue ideas and ways to make their media ideas sustainable.

“I define it as understanding the business models that work in journalism and the challenges that face the industry,” said one, adding, “I think it’s most important for students to learn scrappy thinking and resourcefulness and how to evaluate business ideas financially.”

Many said their media entrepreneurship offerings were intended to build their students’ digital and innovations skills so they could be effective players in the emerging media landscape.

“It’s not necessarily about starting a company,” said one. “I prefer to focus on entrepreneurial thinking: How can we do things differently to meet the needs of our audiences, using the tools and platforms that are appropriate?”

Serving Audiences

Of those falling into the camp of entrepreneurship as an act of innovative disruption that serves a need, one respondent said, “It’s the act of identifying a media problem that needs to be solved and coming up with a new solution. It can be a content or delivery solution. I want my students to understand the media disruption absolutely parallels disruptions in other industries and to be able to recognize patterns that allow disruption to happen.”

Said another: “I have a broad definition of media entrepreneurship. I like the phrase ‘informed communities’ and I believe that anyone who is providing valuable information that is serving a community deserves our help developing a business model that can help make the project sustainable.

“My definition for entrepreneurship is identifying problems and executing on meaningful solutions … The thing I most want students to learn is a sense that with a smart strategy, they can put innovations into place that can change communities for the better.”

Some of the educators teach media entrepreneurship as a stand-alone undergraduate or graduate class. Others incorporate the teaching of media entrepreneurship into classes on innovation or multimedia production skills.

“We’ve actually renamed the class ‘journalism innovation,’ because I want [students] to think not just about starting a business but more broadly about reaching audiences with innovative products and services,” one said.

Two of the respondents, however thought journalism professors should not be teaching media entrepreneurship at all because they have no experience in the subject.

“The prime reason why schools are launching ‘media entrepreneurship’ courses is that they and their students want to continue practicing journalism despite the implosion of legacy mass media news organizations,” said one. Yet, he said, the “grave flaw” in these courses is that most educators don’t fully understand why legacy news outlets are imploding.

“You can’t teach sustainability unless you know what killed the predecessors. Moreover, almost all such courses are taught by professors rich with journalism experience but bereft of business experience.”

The solution at his school: Requiring any entrepreneurial course to be taught by media professors from the business side of news organizations who have also had newsroom experience.

Coming soon will be additional classroom resources, such as case studies and videos, sample syllabi, guest columns and more.

Jan Schaffer, @janjlab, executive director of J-Lab, is also the curator of EdJ, helping the Tow-Knight Center grow the knowledge base for entrepreneurial journalism educators. She teaches media entrepreneurship at American University. Email her with questions, topics you’d like discussed, or ideas for a guest column you’d like to write: [email protected].

The survey findings suggest that within the journalism education world, at least, the term “entrepreneurial journalism” is not sufficient to describe the different types of classes and programs that exist. It reminds me of what happened since the early days of teaching online/digital journalism — at Northwestern’s Medill School we called it “new media journalism” at the time. Back then (say, circa 2000), a class in that subject could cover a little bit of everything — now that single domain has fragmented into storytelling, editing/producing, data visualization, social media, online video, metrics/analytics, etc.