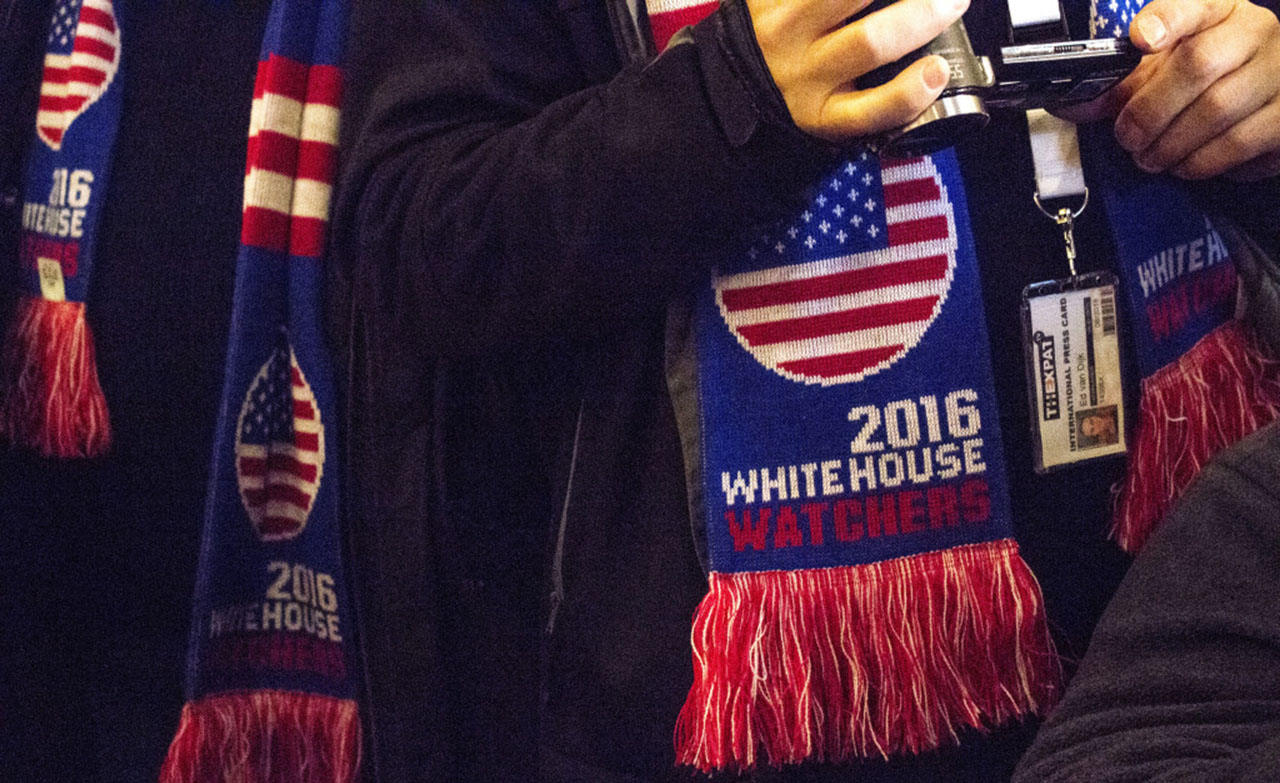

A snowstorm on our first day; the arrival of frontrunner Donald Trump, his family and the Secret Service at our hotel (a Best Western, no less); an Instagram project for The Boston Globe. These are but a few highlights of a trip to expose students to politics and the media during the run-up to the first-in-the-nation primary in New Hampshire last month.

The three-credit class at American University, a semester-long study of the presidential primaries, included this experiential component for the five days before the Feb. 9 New Hampshire primary. Our base camp was Manchester, which gave us easy access to Concord (the capital), Portsmouth on the coast and Nashua to the south, closer to the Massachusetts border.

We are spending the rest of the semester talking about polling, political advertising, campaign strategy, the debates — and media coverage of it all. Our students are working on several analytical papers and also in teams on mini-documentaries based on story ideas they developed in New Hampshire.

We took 40 students of various majors and six members of the faculty. We tweak the model each election season, but it seems replicable in other states and other primaries, though New Hampshire’s small size makes the travel easier.

What worked

• Multiple faculty is a huge help. We had six faculty members from both the School of Communication and the School of Public Affairs. We all had different contacts, unique access to some venues, reporters and political operatives, and were able to offer students a wide variety of experiences.

Shani Rosenstock teaches Professor Richard Benedetto how to use Snapchat. Photo by Anna Sortino, AU.

• A mix of students, not only cross-divisional but from across the university allowed them to learn from each other. In 2008, 2012 and 2016, we found that the wide variety of majors was inspiring and informative. This time around, we have history and economics majors as well as government, political communication, public communication, strategic communication and journalism, among others. We have multilingual students. We have undergraduates and graduates.

• We arranged for small groups of students to get into the spin room at the weekend debate, to go to many different candidates’ campaign rallies and to be on the set with one of the networks taping a Sunday morning news program. We also talked to reporters and editors at print and online news organizations, many of which are based in downtown Manchester during that week. Students traveled in groups of four to six with faculty driving rented minivans. Students rotated among different professors and among themselves.

• The students’ work while in New Hampshire was posted on a class website, and even those new to journalism wrote short stories, uploaded photos and videos and worked in collaboration with others to do so.

• Our hub was a conference room at the hotel that we reserved 24/7 during our stay. This gave us a physical space to call home and a newsroom where we could file stories. We transformed it into our dining hall for pizza dinners and a lunch meeting to hear an invited speaker.

• We booked numerous guest speakers, many of whom we lined up ahead of time. Some graciously agreed to come to our hotel. Others, both media and party officials, said to call when we got to New Hampshire and they would let us know a good time to come to them.

• A professional partnership puts into practice what students have been observing. This year, we collaborated with The Boston Globe on election day. Students went to various polling precincts in seven different cities (selected by the Globe’s political editor, Felice Belman) to interview voters about what mattered most. Each voter wrote his or her key issue on a whiteboard; students photographed them for the Globe’s Instagram account. Students also filed interviews, photos and video by email for use in the Globe’s live blog and in their reporters’ stories later in the day.

• The use of social media by the campaigns and by our students has changed dramatically since we first created the class. This required adjustments to our expectations — we asked students to use Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat and Instagram as if these tools were part of their jobs as observers during the trip, not as partisan voters.

• Flexibility was important. Each election cycle is different, of course. A large field of candidates, controversial issues and heightened security affected access and time to get into a middle-school cafeteria or a high-school gym, a coffee shop or a sports bar to see a candidate. And the time was not the same as it was four or eight years ago.

The unexpected

Rallies were bigger — both Trump and even Bush had larger-than-expected crowds — and the cold and snow made traveling harder. We had backup plans or regrouped when we couldn’t get in somewhere.

The truly unpredictable about any college course — Will the class itself gel? Will the students work well together? — meant there were many unknowns in how well we would function for five days of togetherness around the clock. Building in time for students to work together before the more difficult assignments is essential. We learned that we could have used even more classroom time before heading out on the campaign trail.

Former President Bill Clinton greets supporters at Milford Middle School in New Hampshire when presidential candidate Hillary Clinton traveled to Flint, Michigan. Photo by Sharon Lee, AU.

Yet serendipity always plays a role. We couldn’t have planned finding Bill Clinton campaigning at a middle-school polling site or running into a former student who talked about what it was like to be an embed for NBC.

Just as we didn’t plan to stay at the hotel where the Republican frontrunner was holding his victory party. It was a night in which several students chatted with the Secret Service, watched members of the media run to catch the Donald Trump entourage and chatted with his supporters who were barred from squeezing into the packed conference center. Trump’s confidence, even in the nondescript lobby of a Best Western near the airport, would be a precursor of the primary season.

Lynne Perri is a journalist-in-residence at American University and managing editor of the Investigative Reporting Workshop, a nonprofit news organization affiliated with AU’s School of Communication.