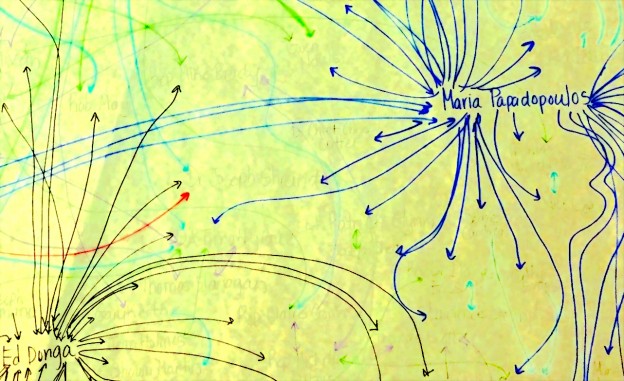

How soon should journalism students be introduced to journalism research? Seniors at FIU used their last semester learning how research can improve news. Image via Ashley Andrews. Click to view project.

Last semester, I wrote about the possibility of incorporating scholarly research related to cultural meanings of news into skills-based journalism classes.

The initial post presented a trial run where journalism students in their final semester explored how selected news outlets reported on specific issues. (See the syllabus and scholarly projects.)

And while the research itself was a good start, we left that experience with key questions about the role of cultural research in a course focused on practice. After another set of students tried their hands at Journalism Studies research, we attempt to answer those questions.

1. How good does research need to be in order to be published?

Across the academy, undergraduates conduct research (see here, here, and here), and there’s evidence that undergraduate research functions as progressive pedagogy with measurable outcomes. Still, journalism and mass communication programs, by and large, tend not to provide rigorous tracks for scholarly research at the undergraduate level.

And like some of the journalism produced in journalism classes, much of the research that can be produced there may not immediately pass the rigor requirements of the profession. So just how polished must that scholarship be to contribute to the field?

A graduating senior from Florida International University’s Digital Media Studies presents an academic poster in 2013 related to his work on media and power. Photo courtesy Robert Gutsche, Jr.

Students’ first answer was to follow standards of peer-review.

Blind peer-review in the academy continues to be debated as a gatekeeper for quality research. (There’s even a whole subset of research watchdogging, particularly in the hard sciences). Still, even at its worst, peer review should provide minor editing, accountability and pressure for excellence.

In the classroom, where many students may have had minimal exposure creating theoretical and empirical research beyond that of the basic “research paper,” there may be few with the experience to critically evaluate that which they themselves are attempting to master. Even the instructor might sometimes be at a loss.

Solution: 1) spend several weeks at the beginning of the semester reading, discussing, analyzing, and comparing forms of writing and interpretation of the academy to that of journalism; 2) expose students to methodologies and applied research.

“In order to be published, research should follow certain normative guidelines, including correct format, the use of peer-reviewed articles to support the arguments, and in-depth personal research into the topic,” said Stephanie Sepulveda, a recent graduate who conducted an analysis of “good” and “bad” news in Brockton, Mass., related to how local media constructed notions of geographic meanings.

Students designed Medium pages for their scholarly analyses as a way to attract wider audiences to academic work. Image courtesy of Stephanie Sepulveda. Click to view project.

“Research, in order to be published, should of course be factual and supported by academic articles and provide a well-developed conceptual framework,” said Maria Bermudez, who examined news coverage of blue zones and socio-spatial dialectics in Albert Lee, Minn.

Marco Briceno, who studied the role of journalistic boosterism, said publishable research should not be opinion-based, but should use academic concepts to support arguments. Excellent answer.

Scholarly research questions guided students as they examined their field of journalism through critical and cultural lenses. Image Courtesy Kathleen Devaney. Click to view project.

We welcome others interested in creating and testing models for conducting rigorous, original research to be in touch to help examine possible standards for encouraging student scholarship that could be shared across the field.

2. What tools should we use to judge student research?

Beyond receiving a clear rubric for evaluation, students need the opportunity to present their work to a panel of respondents.

Interactive maps, such as this one made in StoryMapJS of Albert Lee, Minn., connects academic findings with multimedia storytelling. Courtesy Maria Bermudez. Click to view project.

Many journalism programs do panel assessments quite well already, yet our experiment suggests that these panels are most effective if placed intentionally — and even informally — throughout the course of the semester.

I have often sat on panels to judge student work that are held on the very last day of the course, leaving no time or room for students and instructors to reflect on the assessments and make select improvements.

As another form of assessment, students in my classes are required to share their research projects with reporters and sources who appeared in news coverage that the students had analyzed.

This semester, responses to student requests for feedback and impressions on the analyses were minimal (journalists must be busy bees). Feedback from some reporters, though, proved to be quite telling in terms of holding students to task for their work.

One reporter in particular was critical (rightfully so) of one students’ “reporting” and “research.”

Part of the problem with journalism-related scholarship is often the translation of the intention of scholarly inquiry (problem 1). Additionally, email with this particular journalist also introduced students to a type of professionalized defensiveness that they themselves may (or already might) express in terms of their own work (problem 2).

When responding to the student’s analysis of sourcing — specifically about the degree to which the reporter turned to residents rather than officials — the reporter emailed with a refreshing candor that spoke to institutional pressures of the job.

But it was the reporter’s email response about the student’s inaccuracies — not about the reporter’s work directly, but about the size of the newspaper staff — that spoke volumes to the distance between scholars and practitioners.

This is a small and shrinking newsroom that does not have the resources like the Boston Globe or the New York Times, whose reporters we are compared to. … If you do not take down my name, I will pursue legal action.

The weak threat of legal action aside, the reporter’s comments held students’ feet to the fire in terms of getting not only the facts right, but the interpretations of facts. Students were also exposed, quite personally, to what seemed to be a media producer’s own concerns about having her or his name published online in a forum outsider of her or his direct control.

Lastly, it was a lesson about the fear of threats to the job market, of the freedom of the Internet, and of the simplest of meanings — facts matter and incorrect ones undermine even the most powerful message.

3. How should students and journalists apply research findings?

Several J-School grads who have examined journalism research in my classes return to say that learning about the processes and meanings of research helps them interpret journal articles and scholarly language that they sometimes report on in the newsroom.

Basic journalistic reporting, such as gathering and analyzing demographic data, merged with interpretive analysis to create projects that bridge “thinking” and “doing.” Image Courtesy Maria Serrano. Click to view project.

Students this semester had yet other ideas:

- Students should be aware of accountability in research as in journalistic practice.

- Interpretations, evidence, and claims of causation and correlation can challenge normative explanations of the field.

- Journalism skills curricula can benefit from cultural research.

“Students and journalists should apply research findings by addressing the ideologies that support their work and by having a discussion,” Bermudez said, “the purpose of which is to inform or to bring to light an issue that could better society and media in the future.”

Robert Gutsche, Jr. is an assistant professor in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Florida International University who focuses on geographic place-making and the role of power in news coverage of everyday life. His new book, Media Control, was published in October 2015.