I don’t care.

It’s a harsh statement that always takes people by surprise when they first hear me say it. It’s one of the first external complaints teams must address, and it lands without warning.

Let me be clear, I do care about my teams and their projects. I care deeply about each individual, their goals and their concerns. I care about what students are learning and how to make that experience better and more effective. The students also know I care about them, which is why I can get away with it.

But when a student says “I think” or “I hope” or “I believe” when they are talking about their product or service, my response is always the same. I don’t care.

Thinking v. Knowing

I don’t care what students think, believe or hope about their product. I only care about what they know. If they only hope that something will happen, it probably won’t. If they only think a customer will like and purchase the product, they probably won’t. If they only believe their idea solves a problem, it probably doesn’t.

They need to know. That’s precisely why we do the research. It’s why we build and test prototypes with potential customers. It’s why create revenue models to see if the math works in our favor. It’s why we continuously say, “Go talk to more people.”

It’s not a one-time statement, either. I say it whenever I hear think, hope or believe (or any other similar phrase). Samantha Harrington, the Lab’s summer assistant, made me a flag that reads “I don’t care” to use. I happily wave it when needed because it gets the point across.

Time for Proof

Removing those phrases from the students’ dialogue creates better products. Yes, it’s that simple. Not a single student likes to hear “I don’t care.” It becomes something to avoid, and the only way to avoid it is to prove what they are saying with data and facts. They learn not to say anything that can’t be proven. On the flip side, if they truly believe something, they know they must go out and prove it.

Before long, students begin catching themselves saying those meaningless phrases. When they do, one of three things happens:

- They pause and rephrase the statement to remove the offending words.

- They stop, realize they have no proof and say, “but we still need to prove it.”

- They keep talking and prove the statement by saying something like “we believe this because we heard from 15 customers that.”

It’s important to note this happens all the time. It’s not reserved for formal pitches and practices. We watch for it during team meetings, discussions and impromptu presentations for random lab visitors.

The Power of Know

Removal of these words also boosts confidence. It’s subtle, but when presenting any idea, it’s much more powerful to say “we know” than to say “we hope.” That boost in confidence makes for better pitches, too. Obviously, the more students know about their products, the more confident they will be. Because they have real data to back up their statements, they don’t feel the need to hide anything. It’s empowering.

As counterintuitive as it may seem on the surface, I say “I don’t care” because I actually do.

John Clark (@johnclark) has directed the Reese News Lab since July 2011 and leads courses in entrepreneurship for the School of Journalism and Mass Communication as well as UNC’s minor in entrepreneurship program. Clark has extensive experience as a leader, programmer, research and development manager and startup founder. He is the former general manager of WRAL.com, led the early development of the nation’s first local television news application on mobile phones and co-founded News Over Wireless, now StepLeader Inc. Clark also spearheaded the development of an experimental datacasting service to deliver news and information through digital television subchannels. In 2001, he co-founded appcomm, inc. a local Internet services company. Clark has served on the North Carolina State University Student Media Advisory Board and was an adjunct lecturer of communication at Campbell University for eight years before returning to school for an M.B.A.

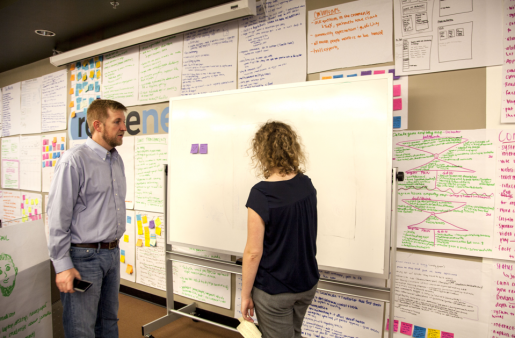

![]() This post originally appeared on Reese News Lab. Reese News Lab is an experimental news and research project based at the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The lab was established in 2010 with a gift from the estate of journalism school alum Reese Felts. The Lab develops and tests new ideas for the media industry in the form of a “pre-startup.” Teams of students research ideas for media products by answering three questions: Can it be done? Does anyone actually need this? Could it sustain itself financially? To answer these questions, students create prototypes, interview and survey potential customers, and develop business strategies for their products. Students document their recommendations on whether they believe a product will work and then present their ideas to the public.

This post originally appeared on Reese News Lab. Reese News Lab is an experimental news and research project based at the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The lab was established in 2010 with a gift from the estate of journalism school alum Reese Felts. The Lab develops and tests new ideas for the media industry in the form of a “pre-startup.” Teams of students research ideas for media products by answering three questions: Can it be done? Does anyone actually need this? Could it sustain itself financially? To answer these questions, students create prototypes, interview and survey potential customers, and develop business strategies for their products. Students document their recommendations on whether they believe a product will work and then present their ideas to the public.