Education content on MediaShift is sponsored by Carnegie-Knight News21, an alliance of 12 journalism schools in which top students tell complex stories in inventive ways. See tips for spurring innovation and digital learning at Learn.News21.com.

This fall, more than 70 million students headed back to school in America, of which 50 million are going to public elementary and secondary schools, and a record 19.1 million are enrolled in colleges and universities. These students are wired as never before — in school, at home, and at every stop in between. It is now commonplace to see third-graders with their own cell phones, and even junior high schools expect students to work from a laptop with an Internet connection.

But at the same time digital technology is a hot topic in education, it’s hotly debated in faculty lounges and parent-teacher conferences, and increasingly, in the broader culture. (The September 19 issue of the New York Times Magazine devoted an entire issue to a dizzying array of articles on the subject.)

The educational benefits of the new technology are more than apparent. Today almost any school in America, however poor or remote, can possess the equivalent of the greatest library in the history of the world, simply by virtue of the Internet. Students can go online to pursue advanced study, and join collaborative communities to add to the world’s store of knowledge. Creative platforms allow young artists and performers to publish and exchange their work.

But digital media also present some educational downsides, both in terms of personal behaviors and classroom dynamics. The formal research is still young, but anecdotes abound. Teachers and professors are in a quandary about student use of laptops in a wired classroom. Many students claim that their computers are necessary for note-taking, but they also sneak looks at Facebook updates and instant messages during the lesson. The problem can become even more acute at home, where students increasingly do their homework by computer. Students have the illusion of multi-tasking as they bounce from algebra to digital games to Facebook and back again.

Multi-Tasking Myth?

Gary Small, professor of psychiatry and aging at UCLA Medical School, is among many scientists who argue that digital multi-tasking is a myth, and holds particular dangers for the young. In one online interview, he explained, “Young people who multitask can complete the task more rapidly, but they make more errors, so we’re becoming faster but sloppier when we multi-task.”

In addition, he said, “There is another mental process related to multi-tasking that’s often called partial continuous attention. Here we’re not just doing two or three tasks at the same time, we’re scanning the environment for new information at any point and this is a process that I think is becoming very popular now that we have all these new electronic communication gadgets, cell phones, PDAs, computers, the Internet.”

Small believes that multi-tasking can contribute to a state of heightened mental stress, which may affect learning and recall.

The problem is by no means limited to America. Maria Mendel, an education professor and vice rector of Poland’s University of Gdansk, believes that the misuse of computers may compromise the study of subjects that require prolonged concentration. Poland has a history of producing world-class mathematicians, but Mendel sees the impact particularly in math.

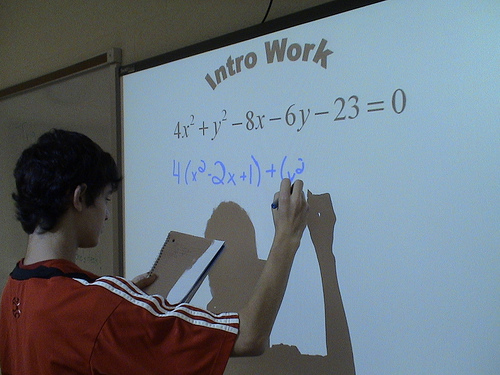

“Many students today have a harder time with complex mathematical formulae, because they’re not used to linear thought patterns,” she said. “They’re used to one-click solutions, and want to intuit answers instead of working through the steps. That just doesn’t work for higher mathematics.”

Computers in the Classroom

The role of computers in the classroom is also under review. Many U.S. schools have invested heavily in technology for smart classrooms in recent years, and the devices are undeniably effective for many functions. But in too many cases, schools have installed the hardware without adequate consultation with the teachers. In some classrooms, the screen may cover the whiteboard, so the teacher can’t project and write at the same time. In others, the orientation towards the screen may limit students’ interaction with the teacher and each other.

Early generations of this technology approached the question from the perspective of “screen as instructor.” But Web 2.0 culture is bending that perspective in the classroom as well, where online tools are promoting an increasingly collaborative environment. Fixed rows of seats facing a “Wizard of Oz” screen just aren’t going to make it — but instructors are going to need a lot more help from the classroom design side to adapt.

Even the most obvious advantage of online media, the retrieval of information, has its issues. It’s no secret that readers of all ages prefer to read shorter material online. With longer texts, the reader tends to take in less of the sentences and paragraphs, with compromised retention, and attention that flags after the initial screen. This generalization is supported by various pockets of research, such as Jakob Nielsen’s eye-tracking studies — though far more research is needed.

Serious students who want to read a long online text carefully usually print it out for best comprehension. (This is more than borne out by my own informal experiments with three years of 75 graduate students, who report that they retain far more of long, complex articles on the page than online.) The readers themselves are uncertain why this is so. Is it:

a) Because type displayed on a backlit screen is less crisp than the printed page’s? (This issue could be ameliorated in the next generation of e-readers.)

b) The distraction of hyperlinks and online advertising?

c) The practice of switching between screens and losing one’s place more easily than in the linear experience of a print-out?

d) All of the above?

Some enthusiasts claim that learning will move away from the text and towards the moving image. They point to the iPad’s emphasis on images as indicative of the path ahead. Nonetheless, linear text is bound to be with us far into the future, especially for intellectual and professional pursuits (such as the law) that require its mental discipline.

These questions must be seriously addressed if we want these cognitive abilities to contribute to our culture.

Distance Learning Coming of Age?

Modes of online learning are also under discussion, as explored by a Columbia student research team. There are bright spots on the horizon. One exciting new study from the Center for Global Development explores the ways mobile phone applications are advancing literacy in Niger. Voice recognition software, such as that used by the wildly popular Rosetta Stone language lessons products, has transformed the process of learning a language, and multiplied the number of languages commonly available for study. But education is also littered with computer-based learning programs that are little more than multiple-choice drills. These may be helpful for rote learning tasks such as typing and addition, but don’t offer much in the way of critical thinking.

In recent years, online learning has been joined at the hip to a discussion of distance learning (once the purview of televised lectures and the “correspondence courses”). A number of for-profit institutions have sprung up that have made particular inroads in “teaching to the test.” The courses hold a special attraction for students who need to pass qualifying examinations for licenses for anything from massage therapy to real estate, but they also enroll legions of students in more traditional academic fields.

The Federal government recently launched an investigation of America’s largest online universities, including Kaplan University and the University of Phoenix, which enrolls 500,000 students on its “eCampus.” These for-profit institutions have been accused of deceptive practices, including misleading applicants with inflated claims about their programs, their accreditation, and job placement rates for their graduates.

Brick-and-mortar universities have put new energy into online distance learning as an additional means to weather the recession, but many of the pedagogical techniques are still under experimentation. Some institutions may pause at the memory of a Columbia-led consortium that launched an online experiment called Fathom.com in 2000. It assembled an impressive roster of educators, but closed in 2003 after it failed to identify a workable business model.

On the other hand, Great Britain’s Open University, established in 1969, has achieved a reputation for excellence, while Australia has led the way in primary and secondary-level distance learning in service of its far-flung students — both emphasizing their online components in recent years.

In the U.S., MIT has led the way in presenting free online lectures by star faculty to enhance its brand, while a number of universities are building out campuses on Second Life. Britain’s Open University has pioneered the integration of Second Life and other virtual reality platforms into its curriculum, and has launched special initiatives to serve housebound and disabled populations.

Educators are seeking criteria to discern which applications most benefit which kinds of learning. Tools for evaluation are scarce on the ground, and the literature is scattered. It’s also clear that more research is urgently needed on the effects of digital media on cognition and the personal interactions that lie at the heart of education.

In January 2010, the Kaiser Family Foundation released a study reporting that American children aged 8 to 18 spent an average of seven-and-a-half hours a day on electronic devices — virtually every waking hour outside of sleeping and school. As William Powers points out in his recent book, “Hamlet’s Blackberry,” this digital time comes at the expense of face time with family and friends, physical exercise, and the experience of the natural world.

Our society’s all-encompassing digital wallpaper constitutes an education in itself. We need to know far more about how it shapes the mind and prompts the appetites if we hope to use it wisely.

Photo of students working at computers by vancouverfilmschool via Flickr

Anne Nelson is an educator, consultant and author in the field of international media strategy. She created and teaches New Media and Development Communications at Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) and teaches an international teleconference course at Bard College. She is a senior consultant on media, education and philanthropy for Anthony Knerr & Associates. She is on Twitter as @anelsona, was a 2005 Guggenheim Fellow, and is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations.

Education content on MediaShift is sponsored by Carnegie-Knight News21, an alliance of 12 journalism schools in which top students tell complex stories in inventive ways. See tips for spurring innovation and digital learning at Learn.News21.com.

this didn’t even help me at all