In times of crisis, communications professionals have an important — and increasingly complicated — role to play. We used to be the first to offer public responses to catastrophes, able to develop elucidating messages before much of the news media was on the scene. Nowadays, the type of media that will report on a crisis is often as unforeseen as the crisis itself. When Chesley Sullenberger, the captain of US Airways Flight 1549, executed a near-miraculous water landing in the Hudson River last month, initial news reports came from the unlikeliest of sources — and beat the official corporate response by a long shot.

Accidental Journalism

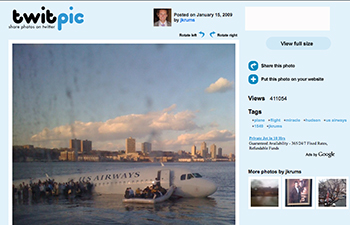

One of the most iconic images of Flight 1549’s bobbing hull came not from a fast-acting photojournalist, but from Janis Krums, a regular guy on a nearby ferry who snapped a picture with his iPhone and uploaded it to his Twitter stream. Before US Airways was able to issue even a preliminary statement confirming the incident, MSNBC had already broadcast the photo and interviewed Krums.

Within 90 minutes of the water landing, an entire Wikipedia page had been created, complete with over 170 edits or additions. Hill & Knowlton’s Brendan Hodgson offers a great chronicle of the page’s evolution. As of this writing, that Wikipedia page trumps the NY Times’ coverage as the first Google result when searching for Flight 1549.

The chain of corporate communications simply can’t keep up with this vast non-linear web of information, so it’s no surprise that media strategists often find themselves in the frustrating position of being alerted to a crisis from precisely the media they’re supposed to be informing about it. Instead of idly waiting for a PR person to develop talking points, the good journalist will abide by her congenital need for speed, and source any information she can unearth among user-generated content…and ask the company official to merely fill in the blanks later.

By the time US Airways was able to issue its initial statement — over an hour after the landing took place — social and traditional media were abuzz with information about the incident. The company seemed to acknowledge the power of the Internet to quickly spread information when its statement read, “US Airways will continue to release information as it becomes available. Please monitor usairways.com for the latest information.” While its intention was good, it was a bit naïve or self-important to suggest that the company website would be the source of “the latest information” when ordinary people using social media have proven able to disseminate news so much faster.

Responding to Responses

When faced with a crisis, we PR professionals no longer have time to strategize about how to break the news to the media and, thus, the public. Instead, we have to strategically repair the news once the public (and, thus, the media) has already broken it. We used to work on explaining events in a way that was prompt, transparent, intelligible and interesting (i.e., “media-genic”). In short, we used to provide information and context in crisis situations. Now, the contextualizing is being wrested from us by a media culture that is responding before we can.

This isn’t just the result of user-generated content. Cable news programs race each other with abandon for new information. By reporting facts stripped of insight or analysis, these shows can sometimes unintentionally and inaccurately frame issues. Some of these frames are benign, but others can be as misinforming as they are misinformed — or under-informed. In this new media climate, Mark Twain’s old adage is especially applicable: “A lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is still putting on its shoes.”

User-generated media is often criticized for not doing original reporting, but instead simply regurgitating, interpreting, and/or bloviating about news originally reported by large conventional news-gathering outlets. To a large extent, the criticism is warranted. I’ll be the first to admit that a large portion of blog content comprises very little original information or opinion. However, in the case of crises, user-generated media is just as likely to inform traditional media as vice versa. This is true of the November terrorist attacks in Mumbai and the May earthquakes in China. In times of crisis, journalists scramble to read blogs and bloggers scramble to read mainstream media accounts.

As previously suggested, this can yield harmful rumors when sources aren’t carefully vetted. However, this cycle can also be symbiotic, where each medium advances the story in its own unique way. More importantly, social media gives communicators the tools to be part of this equation. When his company was criticized last year for a nine-hour tarmac delay, JetBlue CEO David Neeleman offered a candid apology directly to his customers — and outlined corrective steps his company was taking — over YouTube. While the video could have been uploaded sooner, it received media traction, disarmed critics and helped save the company’s reputation.

Tactical responses for crisis communications are changing. Communicators need to be diligent about gathering information and reading all online reports, while still responding expeditiously. As a profession, we’re doing better at the former than the latter. While we’re busy deciding on an appropriate spokesperson, cable news channels and newspapers’ websites are crowdsourcing social media and calling citizen journalists to get their take. The reality is, we’re losing some message control as a result of these new media. If we don’t adapt by making our communications nimbler and more responsive, we’re bound to lose even more. But, if we can be smart about this new medium — the liabilities and opportunities it presents — and rework our strategic approach to crisis communications, we may just stay afloat.

Mark Hannah has spent the past several years conducting sensitive public affairs campaigns for well-known multinational corporations, major industry organizations and influential non-profits. He specializes in issues and reputation management online. Before joining the PR agency world (v-Fluence Interactive and Edelman), Mark worked for the Kerry-Edwards presidential campaign as a member of the national advance staff. He’s more recently conducted advance work for the Obama-Biden campaign. He is a member of the Public Relations Society of America and a fellow at the Society for New Communications Research, and he serves as an awards judge for both organizations. A graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, he’s currently pursuing a master’s in strategic communications at Columbia University. He is an independent communications consultant based in New York City and the public relations correspondent for MediaShift. You can reach him at markphannah[at]gmail[dot]com.

While I understand this point, don’t you realize that there were probably hundreds of family members that deserved to be notified of the accident – and that everyone was okay – before US Airways could pat itself on the back? Their first responsibility is to the passengers and directly contacting all family members. So, seems that the PR team you mentioned did an amazing job in getitng the info to the people who matters – the family – and still them getting out comments for the media in JUST an hour.

How did the lady break her legs in the Hudson river landing?

excellent

User-generated content (UGC), also known as consumer-generated media (CGM) or user-created content (UCC), refers to various kinds of media content, publicly available, that are produced by end-users.