Linking to content is the essence of the online experience — it’s the “Web” in the World Wide Web. But there’s a lot of legal gray area around linking, and surprisingly few court rulings providing guidance as to the circumstances when linking could result in liability.

A court in Canada has now weighed in on the question of liability under Canadian law for linking to an article that contains statements alleged to be defamatory. On the facts of the case, the court ruled that linking to an article containing defamatory statements does not, by itself, constitute defamation. As in the case mentioned in my last post, the litigation arose out of an election-related controversy.

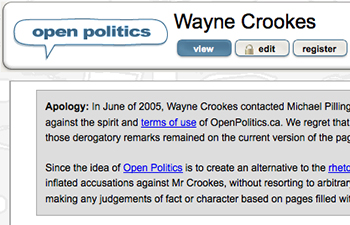

Crookes Versus the World

The individual plaintiff in Crookes v. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. (B.C. Sup. Ct. Aug. 29, 2008) is Wayne Crookes, a Vancouver businessman who was involved with the Green Party of Canada in 2004. Crookes’s involvement in and supposed “takeover” of the party was the subject of three articles on the Canadian-based Open Politics website and another on the (apparently now defunct) usgovernetics website. Claiming that the articles were defamatory, Crookes filed a lawsuit against Michael Pilling, the Canadian editor of the Open Politics site.

Some time later, Jon Newton, founder of digital news website p2pnet.com, wrote about the litigation on his website, including hyperlinks to the allegedly defamatory articles on the Open Politics and “usgovernetics” websites. Crookes responded by suing Newton as well. As will be discussed further below, Crookes also sued not only the Wikimedia Foundation but also Yahoo, Google and Domains by Proxy Inc., a domain name registrar, and numerous other parties for various actions (hosting, providing search results, etc.) relating to alleged defamatory articles and postings about Crookes.

Another Crookes target was widely respected Internet law authority Prof. Michael Geist. Crookes sued Prof. Geist for including a link to Newton’s p2pnet site on his own website.

No Publication, No Liability

Crookes’s underlying lawsuit against Pilling is awaiting trial, as are the cases against most of the other defendants mentioned above. However, in the case against Newton for linking to Pilling’s articles, the court conducted a “summary trial” (a proceeding without a jury,) and ruled in favor of Newton, finding that creating a hyperlink to a defamatory statement does not, by itself, constitute a “publication” of the defamation.

“Publication,” the communication of a defamatory statement to a third party, is a necessary element that must be shown to maintain a claim of defamation under Canadian law. (This is also the case under U.S. law.) In considering whether Newton’s links to the articles constituted a “publication,” the court drew an analogy to a footnote in a print publication, stating: “Where a footnote leads a reader to further material, that does not make the author who provided the footnote a publisher of what the reader finds when the footnote is followed.” The fact that a reader can access the source more easily via a hyperlink than via a footnote in a print publication makes no difference, the court concluded:

Although a hyperlink provides immediate access to material published on another website, this does not amount to republication of the content on the originating site. This is especially so as a reader may or may not follow the hyperlinks provided.

The court also considered the entire context of Newton’s links, noting that Newton had not published any defamatory content about Crookes on his p2pnet site nor did he reproduce any of the content from the articles Crookes claimed to be defamatory. Newton also made no comment on the nature of the articles to which he was linking. Consequently, merely providing links to defamatory content, the court concluded, did not make Newton liable for any defamation in the articles to which he linked.

Be Careful How You Link

Note well that the court did not say that there can never be any liability for linking to defamatory content:

I do not wish to be misunderstood. It is not my decision that hyperlinking can never make a person liable for the contents of the remote site. For example, if Mr. Newton had written ‘the truth about Wayne Crookes is found here’ and ‘here‘ is hyperlinked to the specific defamatory words, this might lead to a different conclusion.

So the ruling is fact-specific. Had Newton endorsed the statements in the linked articles, or added his own “color commentary” to them, the result might have been different.

By the way, the issue of whether the original statements in the articles to which Newton linked were, in fact, defamatory has not yet been decided; the trial in Crookes’s lawsuit against Pillings of Open Politics, originally scheduled for October, has been adjourned.

What Result Under U.S. Law?

If Crooke’s lawsuit had been brought in the U.S. under U.S. law, it might have been resolved in Newton’s favor under the provisions of the Communications Decency Act of 1996. Section 230 of the Act says that providers and users of an “interactive service” cannot be held liable “as a publisher or speaker” for “information provided by another information content provider.” Although there does not appear to be any opinion in the U.S. presenting precisely the same facts as those in Crookes v. Wikimedia Foundation, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act has been interpreted very broadly to protect both providers and users of interactive services from liability for defamation and other torts for “information” provided by third parties.

Canadian Court Used as Guidance in U.S.

One reason to care about the ruling of a Canadian court is that a U.S. court might look to a Canadian ruling for guidance on an issue where there is no binding rule under U.S. law. Canada is our close neighbor both geographically and legally — both legal systems have their origins in the English common law system — and it is not unusual to find courts in each system citing one another’s rulings in subjects, such as libel and slander, where there is a common legal heritage.

An example of that can be found in the Crookes v. Wikimedia Foundation ruling itself, where the court quotes extensively from another Canadian court ruling that, in turn, references several rulings of U.S. courts on an issue of defamation liability. So, if a court ruled that a similar lawsuit was not governed by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, it might look to the reasoning in Crookes v. Wikimedia Foundation to decide on the issue of linking as publication.

In fact, the result in Crookes v. Wikimedia Foundation is generally consistent with the result a U.S. court might reach applying Section 230: An online service provider or user is liable for its own statements, but not for the statements of others.

Getting Sued in Canada

Another reason to care about a ruling by a Canadian court is that a U.S. website operator or other service provider might well get sued in Canada by a Canadian plaintiff for allegedly defamatory statements made online, and either be forced to respond in a Canadian court or risk an adverse judgment. In fact, that’s what happened here. Not only has Crookes sued the Wikimedia Foundation, it has also sued Google and Yahoo and other service providers on the grounds that they are responsible for various defamatory statements and articles about Crookes.

Canada does not have a law equivalent to Section 230 that provides a safe harbor from liability for these entities. In that respect, the results in the Crookes litigations against service providers may be critical to the development of Internet liability law in Canada.

Does a Canadian court have the power to hear a defamation lawsuit brought against the operator of a U.S.-based web service provider? In other words, does the Canadian court have jurisdiction in such a case? In Crookes v. Yahoo Inc., a Canadian appeals court upheld the dismissal of Crookes’s claims against Yahoo for lack of jurisdiction, finding that Yahoo has no physical presence in Canada and that Crookes failed to show that allegedly defamatory statements about him posted on the GPC-Members newsgroup hosted by Yahoo had been read by anyone in Canada.

But other rulings by Canadian courts, such as the 2005 ruling in Bangoura v. Washington Post involving a defamation lawsuit brought in Canada against the Washington Post, suggest that a Canadian court would be willing to exercise jurisdiction over a U.S. website operator or other service provider under the right circumstances. That has happened in Australia, in Dow Jones v. Gutnick, where the Australian High Court upheld the exercise of jurisdiction over the Dow Jones Corp. for an online article that allegedly defamed an Australian businessman. (It is unclear whether the other U.S.-based defendants sued by Crookes have, like Yahoo, moved to dismiss on jurisdictional grounds, although Google has an office in Canada which might preclude it from making a motion similar to Yahoo’s.)

One Final Note

Let us suppose that Crookes succeeded in obtaining a judgment against a U.S.-based service provider and sought to enforce that judgment in the U.S. Would a judgment rendered by a court in Canada be enforced by a U.S. court? A U.S. court might reject such a judgment on the basis that the First Amendment affords the speech of U.S. citizens greater protection than does the law of many other nations. To the extent that a judgment issued by a foreign court might violate the First Amendment rights of a U.S.-based defendant, a U.S. court might find that it is against public policy to enforce it. That important issue has been touched on in several U.S. cases but has not yet been answered.

Jeffrey D. Neuburger is a partner in the New York office of Proskauer Rose LLP, and co-chair of the Technology, Media and Communications Practice Group. His practice focuses on technology and media-related business transactions and counseling of clients in the utilization of new media. He is an adjunct professor at Fordham University School of Law teaching E-Commerce Law and the co-author of two books, “Doing Business on the Internet” and “Emerging Technologies and the Law.” He also co-writes the New Media & Technology Law Blog.

“In Crookes v. Yahoo Inc., a Canadian appeals court upheld the dismissal of Crookes’s claims against Yahoo for lack of jurisdiction, finding that Yahoo has no physical presence in Canada and that Crookes failed to show that allegedly defamatory statements about him posted on the GPC-Members newsgroup hosted by Yahoo had been read by anyone in Canada. ”

Actually, the judge was only concerned about whether it had been read in BC. These are provincial courts, and libel law in Canada varies from province to province. BC’s libel laws are arguably the worst of the bunch.