It’s the year 2028. In your virtual reality (VR) headset, where you can watch the news in an immersive, 360-degree view, the President of the United States is standing in front of you. But are you sure it’s really the president, and not a simulation reciting some troll’s script? Can you trust VR journalists to be honest with audiences and follow journalistic ethics?

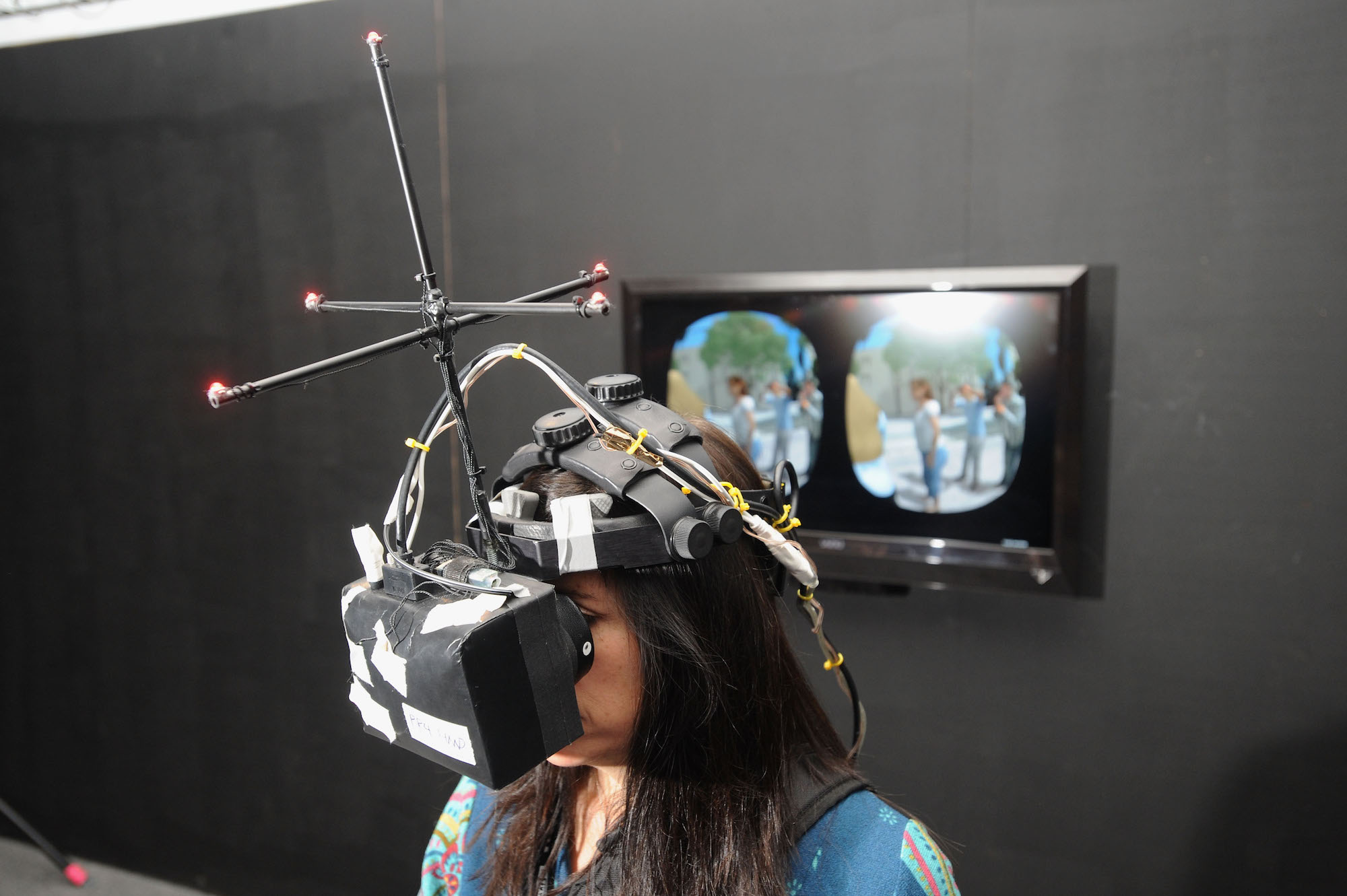

Questions of ethics and transparency are growing among journalists and scholars, as media companies increasingly experiment with the power of VR and augmented reality (AR.) Both technological advances allow users to interact personally with news reports via the creation of virtual scenes viewed through headsets.

Now that misinformation is increasingly a problem for the media industry, the challenge for VR journalism is to prevent dishonest organizations and individuals from producing fake VR work and passing it off as real. Meanwhile, the high cost of creating immersive journalism is cause for concern among some media ethicists.

Is VR a Fad or the Future?

“Immersive journalism,” which brings AR or VR to journalism, was symbolically born on a chilly day in January 2012 at the Sundance Film Festival when documentary journalist Nonny de la Peña presented Hunger in Los Angeles, about the lack of food in some Los Angeles neighborhoods. Reporters described audiences there as “visibly affected.” Simply by putting on a headset, viewers could leave behind a snowy day in Park City and be transported to a warm day at a food bank in downtown L.A.

At that point, the term “VR journalism” was only used by technologists and a small circle of tech journalists pioneering efforts in the field. That August, the small startup Oculus Rift launched a Kickstarter campaign that raised $2.5 million to develop its second prototype VR headset. Two years later, Facebook bought Oculus for $2 billion. By early 2016, immersive reporting was showing up in newsrooms across the United States, including The New York Times, CNN, USA Today, The Guardian, AP.

And some projections suggest that VR could have staying power. According to UK-based consulting company CCS Insight, the global VR market will be worth over $9 billion by 2021. Goldman Sachs projects that the combined global economic impact of VR and augmented reality (AR) will grow to $80 billion by 2025 (up from $2.5 billion in 2016).

The Ethics of VR

James Pallot, VR storytelling pioneer and co-founder of the Emblematic Group with de la Peña, faced an ethical dilemma.

In 2017, Emblematic had worked with PBS’ Frontline to create a climate change story called Greenland Melting, about the Greenland Ice Cap. The report used a hologram of the scientist Eric Rignot (professor of Earth system science at the University of California, Irvine, and a scientist at NASA) to narrate the story.

“To make the hologram, we had to bring [Rignot] to our lab in L.A.,” Pallot said in an email interview. “But we had to debate: should we wear normal clothes for the interview, since he was in L.A.? Or should he dress up in his cold-weather gear, so it would look more ‘realistic’ when you see him standing on the ice?” They ended up dressing Rignot in a light jacket.

“It may sound like a trivial question but it goes to the heart of the matter. VR has an incredible power to make you feel like you are actually ‘present’ in a different place, and you must be careful not to exploit that illusion, to let the viewer know what is real and what isn’t, and what was the process to create this illusion,” Pallot added.

In 2016, philosophy professors Michael Madary and Thomas Metzinger published a paper titled Real Virtuality: A Code of Ethical Conduct. This paper pointed out that VR is a “powerful form of both mental and behavioral manipulation” that could be tricky, “especially when commercial, political, religious, or governmental interests are behind the creation and maintenance of the virtual worlds.”

“We need more research into the psychological effects of immersive experiences, especially for children,” Madary told me. “We should inform consumers that we do not yet understand the effects of long-term immersion,” such as “whether VR can have an influence on their behavior after leaving the virtual world.”

VR can be a journalistic tool that allows consumers to transcend time and space. The Displaced, for example, is a VR documentary from 2015 produced by The New York Times Magazine. It depicts the lives of three young children refugee in Syria, Ukraine and South Sudan and allows viewers to feel like they’re present with the children. Or On the Brink of Famine, a 2016 documentary from PBS Frontline and The Brown Institute for Media Innovation, about a village in South Sudan dealing with a hunger crisis.

Douglas Rushkoff, shown here the 2013 SXSW Festival, believes VR and journalism are incompatible. (Photo by Waytao Shing/Getty Images for SXSW)

But Douglas Rushkoff, media theorist and an outspoken critic of Silicon Valley, argues that those types of VR documentaries do not qualify as journalism at all. “I think immersive media has a really limited purpose, certainly in terms of journalism and informing people. I guess you can make people feel certain ways by immersing them in certain kinds of worlds. But in most of these experiences you are just watching people who can’t see you, so in some ways it exacerbates the sense of power that privileged people can feel over less privileged people.”

VR and Fake News

One of the most troubling threats from the incursion of VR into journalism is the possibility that fake news organizations and trolls might start producing VR fake news.

Increasingly, media theorists such as the interdisciplinary scientist Jaron Lanier and the director of the MIT Center for Civic Media, Ethan Zuckerman, are calling for VR journalists to create a code of ethics.

Tom Kent — president of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, a U.S. government-funded broadcasting organization — was one of the first journalists who talked about the ethical challenges of VR reporting. In a 2015 Medium post, he opened the debate on ethics in VR and journalism, with a focus on fake news, long before the 2016 presidential election.

“In a few years, it may well be that virtual reality will begin to simulate news events using images of newsmakers that will be indistinguishable from the actual people,” Kent told me recently. For example, “a VR recreation of a scene involving Putin or Obama, maybe so accurate you can’t tell whether that’s the real Putin, or the real Obama, or whether they were virtually recreated.”

“People who do VR journalism need to have an ethical code, and they need to publish that code, and they need to explain their ethics,” added Kent. For example, viewers need to know if the action on the VR piece is scripted or not and whether the dialogue was captured from a real setting or scripted.

VR Can’t Support Itself Financially

A 2017 report by the Reuters Institute, VR for News: The New Reality?, delves into the cost of VR journalism. Productions are still expensive, resulting in a lack of quality content, which in turn negatively affects the potential for ad revenue, the report said.

Another study by the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University found that “The cost of highly produced VR work would seem to have implications for viable business models in the short term. If the best cost comparison is with high-end TV or console game production, it is likely that currently producers and commissioners will need to produce high-end journalistic VR without an expectation of direct cost recovery from audiences or advertisers.”

Rushkoff considers VR to be nothing more than advertising, and says it cannot be part of quality journalism. “Once journalism changed from something that people purchase in order to be informed to something that advertisers pay for in order to get people’s attention,” Rushkoff said, “then all the technologies that have been deployed for journalism have way more to do with helping advertisers to spread their message than informing people.”

The real hope for VR journalism is that newsrooms could create experiences based on reality and with the same ethics of photojournalism: photos aren’t manipulated, and photographers only show what they see. In order to do so, VR journalism has to become financially independent. If it must rely solely on sponsorship from big companies to survive, Rushkoff might be proven correct.

Angelo Paura is an Italian journalist based in New York, working with Il Sole 24 Ore Usa. He writes for major Italian magazines. He studied immersive journalism for a Masters in social journalism at CUNY Graduate School of Journalism. He is focused mostly on digital cultures, new media, technology and politics. He loves empty spaces, walks on the slackline, mezcal and drawing monsters. Reach him at [email protected] or @angelopaura.