Products and technology are human in design and represent the vision of a leadership team. Product features are ideas, approved by teams of people who often do not come from diverse backgrounds. Features are prioritized based on the goals of the project and company.

For a public company like Twitter, that means driving revenue for shareholders. All of these factors create an environment that is ripe for biased products and platforms that ignore the needs of underrepresented groups, such as people of color, women, and LGBTQIA+ people. Products often reflect the diversity (or lack thereof) of the people who create them.

The case of the emoji

In April 2015, Apple released a new set of “racially diverse emoji” intended to more accurately reflect the diversity of its users. In November, I noticed one of the new emoji in Oprah’s tweets. The emoji was intended to appear as a brown fist, but it was displaying as a white fist with a black swatch next to it. Clearly, this is not what the emoji creators had intended. Soon after, 50 Cent posted a tweet that had black praying hands being displayed as white praying hands with a black swatch. This tweet was then embedded in an Adweek post. I then realized that any racially diverse emoji that appeared in news and media stories would display incorrectly and be distributed globally, adding to the insult. This Twitter product feature was marginalizing people of color and reinforcing institutionalized racism.

When it comes to social media technologies and media education, the focus is often on how technologies shape storytelling and journalism, but what about the biases that they potentially create? I took a screenshot of the emoji swatch issue during a Twitter conversation between prominent Black Lives Matter activist DeRay Mckesson and writer Shaun King and incorporated this into a class discussion around emoji and biased product development. Many students reported that they had seen the issue and recognized that it was a technical glitch. Generally, people understand when technology is broken, but what is less understood is that it was someone’s decision at Twitter to leave that error in place, to not issue an apology, to not address it for more than 232 days. This issue wasn’t a priority for the company. This is a problem.

Apple introduced racially diverse emoji in 2015 and expanded offerings in December 2016. Image courtesy of Apple.

A new lesson

The lesson could have stopped there with merely identifying issues. But these students will become journalists and communicators who rely on media companies and their social media platforms. They need the skills to effect change on platforms that they use. I had planned to cover the latest social media technologies, analytics, social media marketing, social listening — to help them learn how to self-teach in order to stay relevant in emerging media. I didn’t realize that I had developed a skill in corporate that would be so valuable — I was primed to identify biased product development. My industry skills lead to a social-justice campaign in my first semester teaching.

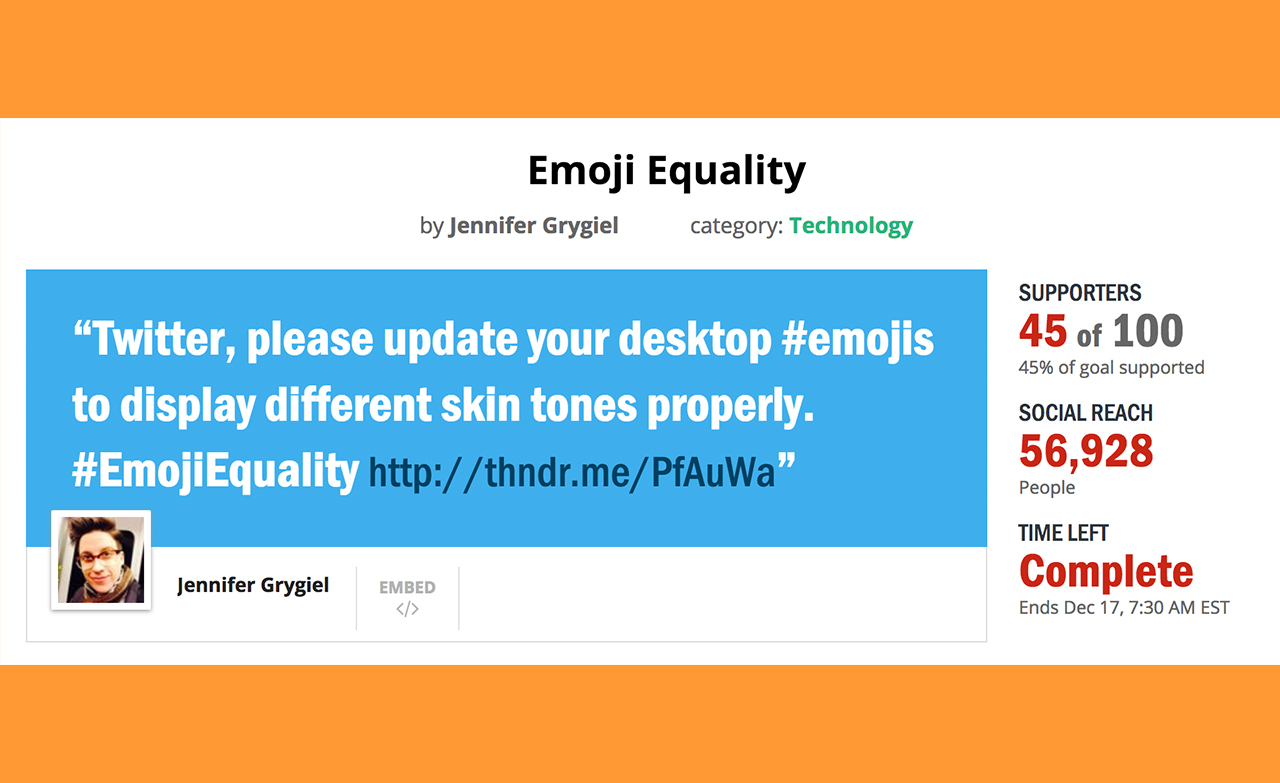

At the end of the class, students were invited to join a Thunderclap campaign — a social media site that can be used for collective action and activism — to ask Twitter to make the product update and to display racially diverse emoji correctly. Before the end of the Thunderclap campaign, the students who participated generated a social reach of more than 56,000 people. Twitter ended up correcting the emoji issue in the middle of our campaign. I can’t prove that we helped prioritize the update, but we might have.

This lesson helped to teach students about social media and product development, as well as the importance of being an engaged digital citizen and professional. As journalists and product developers in training, students need to be aware of how social inequalities are reproduced in products, how this marginalizes communities and individuals, and how ethical issues in business can impact us and reinforce issues such as institutional racism and oppression.

Jennifer Grygiel is an Assistant Professor of Communications (Social Media) at the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. In 2016, Grygiel took first place in the Best Practices in Ethics in an Emerging Media Environment teaching competition, sponsored by the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC) Elected Committee on Teaching.