Journalism education faces multiple challenges in making sure students are learning basic news gathering and reporting skills but also adept with various digital technologies and platforms. Students entering newsrooms now are expected to know how to write a story, take digital photos, capture audio, make multimedia packages, create infographics, and know code to make apps or websites. Another skill and technology that can be added to the mix is sensor journalism.

What is Sensor Journalism?

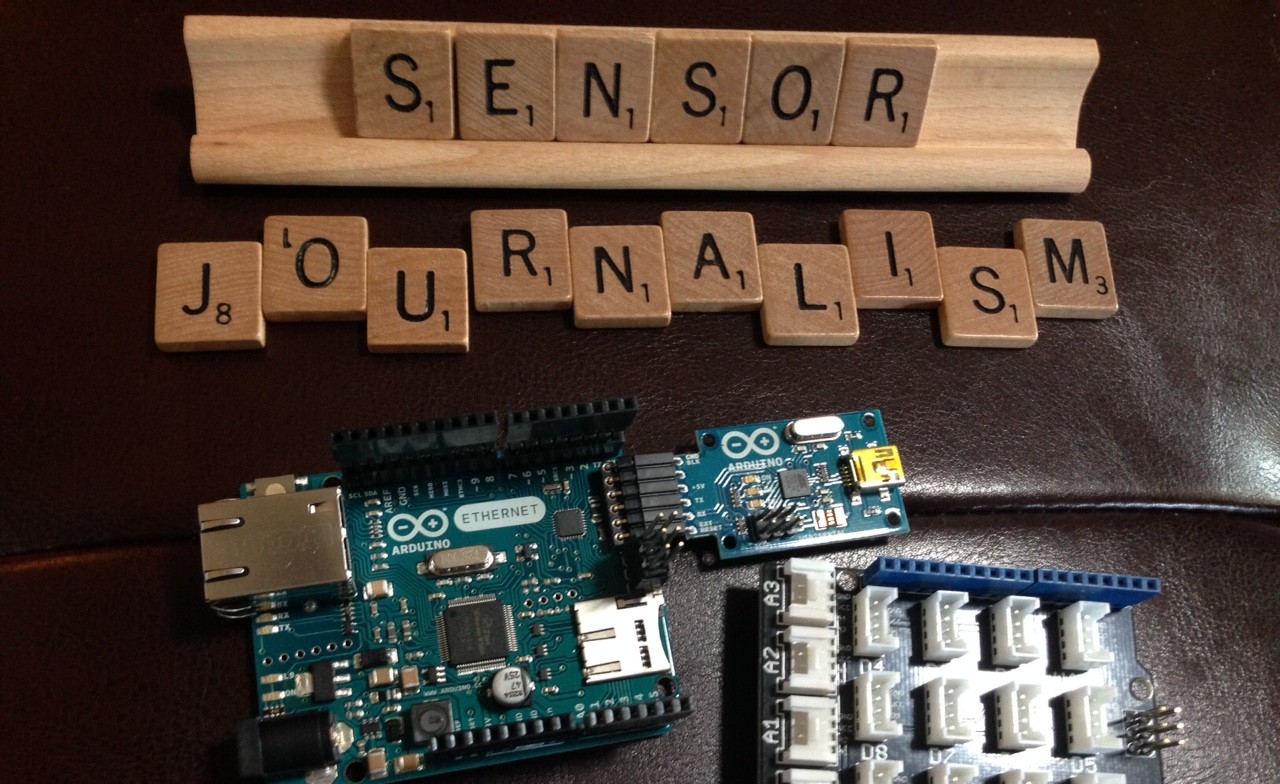

Sensor kit components from air quality project. Photo by Amy Schmitz Weiss.

Sensor journalism can be defined as using sensors as part of the newsgathering and reporting process for a specific kind of story that requires a sensor to gather and report data. Such data can include but is not limited to information about what is in the water, air, temperature, wind and soil.

Sensor journalism is not new — many news organizations have been using sensors for powerful storytelling for years. Some recent cases include The Houston Chronicle’s investigative story “In Harm’s Way,” where they used sensors to examine air quality where people lived near oil refineries and factories. The investigation identified poor air quality in the area despite state and federal regulations showing the factories and refineries were within legal limits. USA Today’s “Ghost Factories” series examined soil contaminants from old metal factories. The reporters used x-ray gun sensors to scan the soil. Their analysis showed several sites were above the EPA’s limits in terms of arsenic and lead.

On a less serious topic, at WNYC in New York, they used sensors to track insects called cicadas. WNYC found out that cicadas could be predicted based on soil temperature, so they created an electronic sensor that citizens could put in their soil to track the prediction of cicada arrival in the northeast. They collected 1,750 temperature readings from 800 different locations from listeners who wanted to be a part of the project.

All of these examples highlight how the power of a story and an environmental issue or concern can be enhanced through the ability to use sensors to collect data about a specific aspect of the environment.

Nowadays, the technology used in sensors has become more affordable and easier to work with as open-source electronic hardware and software like Arduino and Raspberry Pi have entered the market.

Journalism Educators Doing Sensor Journalism

Some journalism educators are exploring this realm of sensor journalism in the classroom. For example, Susan Zake at Kent State University explored water quality with her students last spring using Raspberry Pi to create some effective sensors. Florida State University Professor Robert Gutsche explored rising sea levels in Southern Florida with his students last year in a special water sensor project called “Eyes on the Rise.” And recently, West Virginia University’s Reed College of Media announced they are working with John Keefe and others on a special project to explore water quality in the area with sensor technology.

What’s in the Air Sensor Project

Students building the air quality sensor kits in the first few weeks of class. Photo by Amy Schmitz Weiss.

I also had the opportunity this past year to embark on a sensor journalism project called “What’s in the Air” through a grant I received from the Online News Association called the Challenge Fund for Innovation in Journalism Education. Through this grant, I was able to bring together science and journalism students and work along with a nonprofit news organization, inewsource, to investigate air quality in San Diego using open-source electronic sensors. The project led to nine in-depth stories published on the inewsource website about air quality in four different neighborhoods in San Diego and an interactive map showing the sensor data collected by the students during the project.

How to Embark on a Sensor Journalism Project

Based on this experience, I thought I would share some tips in case you may be thinking of venturing into teaching sensor journalism in your program:

- Have an issue to tackle. In our case, we identified an environmental issue that we wanted to explore — air quality. This allowed us to set the learning outcomes for the class and spend the time to investigate a variety of air quality sensors that allowed us to find the appropriate technology for our project. We also identified several datasets that allowed us to explore how air quality data was being collected in the city. This gave us a foundation by which to explore the nuances of that data and go deeper into the community with our own sensor kits.

- Beta-test the sensors. Sensors are becoming cheaper and thus the quality you get with each sensor will differ. You should beta-test as many sensors as possible to see what issues arise, so you can opt for the best version.

- Hit the ground early. I had the students build their sensor kits within the first two weeks of the class, so they could get to know how their sensor worked and hit the ground running with their news gathering and reporting. The students enjoyed the experience of building it themselves and formed an affinity for it, even giving special names to their sensors as they used them throughout the semester. Some of the students kept their sensor kits at the end of the semester as a memento of the project.

- Have a solid technical infrastructure in place. You should identify several months before how you will collect the sensor data and where it will be housed. In our case, we created sensor kits that allowed the user to collect the data via miniSD card or Ethernet connection. We also set up a website to collect data and host it as we progressed from week to week in the course. You should have a long-term strategy for data storage after the project has ended.

- Student vs. community involvement. You should determine before the class launches if you will involve the community or just have students participate. In our case, we posted a Google Form to solicit community interest. This allowed us to know how the community member wanted to get involved (e.g., getting news updates on our project or having one of our sensor kits deployed in their own backyard).

- Community Communication. If you do go the route of bringing the community into the project, make sure you provide a letter in the beginning the explains the overall project, the extent of their involvement in the project, how to use the sensor, what the sensor is collecting, how to read the sensor data and the overall premise of the project. Make sure to keep the community updated on the project as it develops. In our case, I sent updates to the community every month, so they knew where we were with the project. In some cases, some of the community members had news for me in terms of their development of a new version of the sensor kit we had given them, and I was able to inform the students and the community about these updates too.

- Have technical support on hand. It’s important to have a plan for how you will handle issues and troubleshoot if you have problems with the sensors. In our case, we did have some components from the manufacturer that failed to work or failed working at some point in the project and we had to figure out next steps. We also had some community members who needed help getting their sensor kits connected to the website. In some cases, their sensors stopped working, so having a clear plan for technical support will be helpful. I had a great technical guru who assisted with these issues. Don’t make yourself the tech support person, as it can become too much if you are also managing the project and class.

- Create online tutorials for assembling the sensor. We used online tutorials that were step-by-step pictures of how to build the sensor that we used during the build days in the class and also shared these tutorials with the community when they were building their sensor kits. People could revisit these tutorials as needed.

- Collaborate. For our project, we worked with a local nonprofit news organization, science faculty, the Public Health department on campus (they were crucial in helping us to corroborate the data from our sensors and help us with the calibration of our sensors), and we sought out advice from journalism gurus like Sean Bonner, Lise Olsen and John Keefe. Sensor journalism projects are not meant to be implemented in a vacuum but with collaborators. So make sure you have colleagues on and off campus who you can partner with to make it a successful project.

Are you seeking more tips? I have posted other resources on my website that include the class syllabus, details of our sensor kit build and its components, where to purchase sensor equipment, readings for the classroom, the students’ work on the project, and the blog that chronicles our experience from this past spring that you may find helpful: http://sensorjournalism.wordpress.com/

I am happy to share any other tips or advice. Feel free to drop me a line at [email protected].

The What’s in the Air project was administered by the Online News Association with support from Excellence and Ethics in Journalism Foundation, the Robert R. McCormick Foundation, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Democracy Fund, and the Rita Allen Foundation.

Amy Schmitz Weiss is an associate professor in the School of Journalism and Media Studies at San Diego State University. Schmitz Weiss is a 2011 Dart Academic Fellow and has a Ph.D. in journalism from the University of Texas at Austin. She teaches journalism courses in writing and editing, multimedia, web design, data journalism and mobile journalism. Schmitz Weiss is a former journalist who has been involved in new media for more than a decade. She has worked in business development, marketing analysis and account management for several Chicago Internet media firms. Her research interests include online journalism, media sociology, news production, multimedia journalism and international communication. Contact her at [email protected] | @digitalamysw