A renowned media critic sounded the alarm in 1960 about corporate takeovers of newspapers and layoffs of hundreds of journalists. He worried that the power of the press was being concentrated in too few hands.

It was in his column in the New Yorker, The Wayward Press, that A.J. Liebling tossed off one of his most memorable lines in a parenthetical aside:

“Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one” (New Yorker, May 14, 1960, p. 109, paywall).

What is still true today is that corporate owners of newspapers are focused on maintaining their profit margins and are laying off journalists to do so. The newspaper and magazine industries have lost 54,000 journalism jobs since 2003.

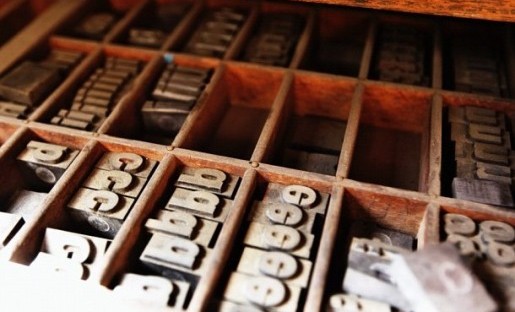

But it is no longer true that newspapers monopolize production and distribution of news. The Internet has given everyone with a computer and Internet access their own printing press. You do not have to be a mogul to publish your opinions. The big question is: Can you get anyone to listen?

Control of public opinion

Liebling’s demons have been defeated; they no longer dominate public discourse the way they did. What is less well known is that there is a new group of monopolizers. Public discourse is now becoming concentrated in the hands of a different handful of corporate entities, and they are not newspapers or media companies.

Today it is Google, Facebook, Yahoo, Twitter, and other platforms whose algorithms shape the news feeds their users rely on to inform themselves about the world. For some, these platforms are their main source of news.

Liebling did not foresee these Internet platforms, but he did worry about how corporations can manipulate public opinion. In the 1950s, corporate profiteers were buying up and shutting down dozens of newspapers with the aim of making an extremely profitable business even more profitable. Hundreds of journalists were being laid off. Newspapers with dissident voices were being silenced.

(On a personal note, my brother lost his job as a newspaper boy when the Cleveland News shut down in 1959. I was an editor at the Columbus Dispatch in 1986 when it became the sole daily in town with the closing of the Citizen-Journal, itself the product of a 1959 merger. My hometown Cleveland Plain Dealer became the only daily with the closing of the Press in 1982, and the negative consequences for press freedom were recently highlightedby Jay Rosen.)

Few choices for journalists

With all the mergers, Liebling saw a trend toward ownership with a more uniform conservative point of view:

“What you have in a one-paper town is a privately owned public utility that is Constitutionally exempt from public regulation, which would be a violation of freedom of the press. As to the freedom of the individual journalist in such a town, it corresponds exactly with what the publisher will allow him. He can’t go over to the opposition, because there isn’t any.”

Liebling responded bitterly to all the cheery speeches he was hearing that month at the American Newspaper Publishers Association annual meeting. The lords of the press were predicting greater profits and efficiency, as well as better journalism, as a result of all the mergers.

Illustration of A. J. Liebling by Jburlinson and used here with Creative Commons license.

Liebling would have none of it. His critical counterpoint appeared under the headline, “Do You Belong in Journalism?”, which was the same as the title of a book he proceeded to savage. The book was written by newspaper editors and publishers who were urging young people to pursue a career in the romantic field of journalism.

He singled out with irony this quote from a publisher: “The income of newspapers is generally quite even, and the danger of losing one’s job to sudden and perhaps temporary slumps is remote.” Of course, snorted Liebling; what would you expect from the owner of a paper with no competition? (He was referring to the Longview, Wash., Daily News, which eventually was sold to a chain and is now owned by Lee Enterprises, which owns 50 newspapers.)

Given the merger trend, Liebling wrote,

“If a journalist is working in a town where there are two ownerships, he is even money to become unemployed any minute, and if there are three, he has two chances out of three of being in the public relations business before his children get through school.”

Despite Liebling’s dire predictions, employment for journalists grew along with industry profits for the next 47 years until the global financial crisis and the impact of the Internet hit at the same time.

Google and Facebook rule

Today anyone can write and publish anything they want on the Internet, but whether it gets noticed and distributed depends on whether others see and distribute it through web pages, blogs, and social media accounts.

Social media like Facebook and Twitter, and search engines like Google and Yahoo, are critical for creating the audience for a news organization. Facebook drives about 20 percent of the traffic to news sites, and news editors consult with the 26-year-old whose team designs the news algorithm to figure out how to make that increase. Google provides about a third of the traffic to news sites.

Nothing proves the importance of these platforms to the future of news more than the industry that has sprung up around search engine optimization and marketing in social networks.

The invisible hand

All the algorithms that calculate what is relevant to a user are based on subjective human judgment, not news value or public interest, as Jay Rosen recently pointed out. Those human beings could consciously or unconsciously manipulate public opinion.

How will the financial goals of these companies affect how they tweak their algorithms? Google has more than 30 percent of the world’s $140 billion in digital advertising, according to eMarketer. Google and Facebook together have more than 70 percent of the world’s mobile ad revenue. Twitter is moving in the direction of a filtered feed to boost business results, according to Gigaom’s Mathew Ingram.

Of course, the Internet is big enough that no one has to use Facebook or Google to get their news. They can get it anywhere, so why should we be worried? The argument was similar in Liebling’s day, and he did not buy it.

In theory, Liebling wrote, you could always buy an out-of-town newspaper if you did not like the voice of your hometown paper. In practice, though, it was not so easy, he said. “In any American city that I know of, to pick up a paper published elsewhere means that you have to go to an out-of-town newsstand,” which he argued were hard to find and had only expensive papers that were out of date. And in small towns, out-of-town newsstands didn’t exist.

Forced and self-censorship

The truth is that most Internet users — who are by some definitions, lazy, selfish, and ruthless — do not go beyond the most prominently recommended links. So what Facebook and Google recommend will have significant impact on news consumption.

And who do Google and Facebook respond to? Since they are publicly traded companies, their first responsibility is to their shareholders. Just as with the shareholders of newspaper companies, public service and freedom of expression are not necessarily their priorities.

One only has to scan the Wikipedia entry for Censorship by Google to find dozens of articles about how the company has either willingly or by force of law censored its results. In other words, heavy-handed governments can filter the information you get.

In 2008, for example, Google gave in to demands from the Pentagon to remove from Street View any images of U.S. military bases in the interest of national security.

National security is invoked frequently in the name of not publishing information, and sometimes news organizations comply. So if a whistle-blower wants a story to get out, they can shop the story to many news organizations and one of them might publish it.

But if Google and Facebook comply with censorship requests, those kinds of stories are less likely to rise to the viral level of public attention. The organizations best equipped to make a story turn viral are vaccinating the news. Viral free could mean news free. Liebling would not have approved.

This post originally appeared on James Breiner’s blog: newsentrepreneurs.com.

James Breiner is a bilingual consultant on digital journalism with three decades of experience on the editorial and business sides of newspapers. His specialty is entrepreneurial journalism. He has done work for the Poynter Institute, International Center for Journalists and the Fundacion Nuevo Periodismo Iberoamericano (Garcia Marquez Foundation). He is currently visiting professor of communication at Tecnologico de Monterrey in Mexico.