A recent U.S. court decision clarified that media organizations cannot assume that photos shared via Twitter are rights-free, to be used as though they were in the public domain.

In the case of Agence France-Presse (AFP) v. Morel, U.S. District Judge Alison Nathan ruled in favor of freelance photographer Daniel Morel. Her judgment: Both AFP and the Washington Post had infringed on Morel’s copyright.

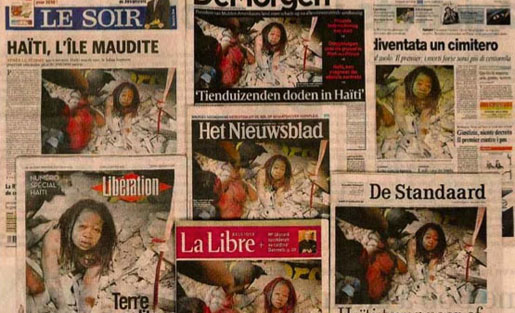

Not unlike last week, when some British news organizations published front-page photos of a helicopter crash sourced from Twitter, in January 2010 AFP lifted Morel’s photos of the Haitian earthquake from Twitter/Twitpic and distributed them on its wire service.

These cases raise big questions, including where does copyright law and Twitter’s terms of use intersect? How can media organizations best serve their audience, particularly in a breaking news scenario? What can photographers — professional and amateur — learn from Morel’s experience?

Morel, a former AP photographer, was in his native Haiti at the time of the earthquake, January 12, 2010. He created a new Twitter account and uploaded 13 photos to Twitpic.

As Photo District News reported, after Morel realized AFP and Getty had appropriated his photos, his agent, Corbis, sent take-down notices to Getty and AFP, but it took AFP two days to issue a kill notice. Moreover, the photos had also been falsely attributed to Lisandro Suero; some of these photos can still be found on news sites.

AFP’s argument — that the Twitter terms of service allowed it to not only distribute his photos without permission but also distribute them through Getty Images — was untenable. Judge Nathan wrote:

“[T]he Twitter TOS (terms of service) provides that users retain their rights to the content they post — with the exception of the license granted to Twitter and its partners — rebutting AFP’s claim that Twitter intended to confer a license on it to sell Morel’s photographs.”

Clearly, the photos were powerful. Morel won the 2011 World Press Photo contest for spot news. Also in 2011, Morel settled with ABC, CNN and CBS.

Was the act — AFP’s copyright infringement — willful? The judge left the answer to that question to a jury.

What tripped up AFP?

In the lawsuit, AFP claimed that because “Morel posted several photographs on Twitter in full resolution“ that there was “no limitation on their use.”

Morel argued that the Twitter terms of service did not grant AFP the right to use his photos without permission. His images were publicized on Twitter but hosted on Twitpic. At that time, the Twitpic TOS made content ownership clear:

“By uploading your photos to Twitpic you give Twitpic permission to use or distribute your photos on Twitpic.com or affiliated sites

All images uploaded are copyright © their respective owners”

So did the Twitter TOS (emphasis added):

“You retain your rights to any Content you submit, post or display on or through the Services…

You agree that this license includes the right for Twitter to make such Content available to other companies, organizations or individuals who partner with Twitter …”

AFP was not an affiliate of Twitpic nor a partner of Twitter. Moreover, Twitter provided detailed guidelines for republishing tweets and images that had been shared on the service, guidelines not followed by AFP. The judge continued:

“[T]he Guidelines further underscore that the Twitter TOS were not intended to confer a benefit on the world-at-large to remove content from Twitter and commercially distribute it: the Guidelines are replete with suggestions that content should not be disassociated from the Tweets in which they occur.

[…]

“AFP and the Post raise no other defenses to liability for direct copyright infringement and, in fact, concede that if their license defense fails — as the Court has determined that it does — they are liable for direct copyright infringement.”

According to Barbara Hoffman, attorney for Morel, a February 1, 2013 court appearance has been adjourned. She anticipates a jury trial in April or May, depending upon the court calendar.

And then there’s BuzzFeed

In the wake of this decision, BuzzFeed appears to be walking a risky path, according to this analysis from Poynter. The company is presenting sponsored posts — in other words, embedded ads — that rely on web-sourced content.

In a sponsored post from 2010, BuzzFeed appropriated a copyrighted photo published first on The Daily Mail. The photo on BuzzFeed was cropped to remove the photographer’s ID and copyright line. And someone slightly modified the color of the sky.

Last year, Alexis Madrigal delved into BuzzFeed’s practice of lifting photos from the web. BuzzFeed founder Jonah Peretti argued “fair use“:

“Peretti told me that he considers a BuzzFeed list — its sequencing, framing, etc. — to be a transformative use of photos. That is to say, including that unattributed photo of the otter in that list was OK because its inclusion as an ‘extremely disappointed’ animal transformed the nature of the photo.”

That argument seems almost as quaint as AFP arguing that links to photos shared via Twitter made the photos fair game for media organizations to appropriate and sell.

The behavior at BuzzFeed continues, apparently unabated. For example, in a January 2013 sponsored post for the Nevada Tourism Commission, BuzzFeed embedded four photos from Flickr that are Creative Commons Licensed images, but the licenses prohibit commercial use. There is nothing on the post acknowledging that BuzzFeed has obtained the right to use the images commercially. Because one of the photographers is licensing his Flickr photos for commercial use via Getty Images, a logical addition to his credit line would be “used under license” or “Flickr/Getty Images.”

Last year, Madrigal wrote:

“[I]t’s very strange that Pinterest and Tumblr users don’t have to play by the same rules that media editors do…”

But they do, when it’s other people’s work. In other words, Tumblr and Pinterest users cannot legally appropriate someone else’s photos and publish them as their own.

First, Tumblr. When someone uploads an image to Tumblr, she is asserting that she owns the rights to that image. To do otherwise is a violation of the TOS and makes the account holder liable for any copyright claim that might be directed at Tumblr.

The TOS at Tumblr expressly allows sharing (reblogging) content on Tumblr.com. That’s the price being paid, so to speak, to use the service. So that’s why it’s legal to share an image within the Tumblr sandbox.

Second, Pinterest. When someone “pins” an image on Pinterest that is hosted on another website, the account holder is supposed to link back to the original source. When someone uploads an image to Pinterest, just as on Tumblr, she is asserting she has the right to do so.

And the TOS at Pinterest also expressly allows sharing (repinning) content on Pinterest.com.

Neither behavior reflects what BuzzFeed is doing with its sponsored posts, posts that may contain a dozen or more images harvested from around the web and published in one advertisement on a for-profit media outlet.

Advice for media organizations

It seems like common sense, but understand the terms of service on websites that host images before you appropriate a photo. And recognize that some services like Flickr host photos with a range of licenses, from generous (commercial use allowed) Creative Commons ones to locked-down, must-be-licensed-to-use copyright.

Failure to do so can be costly, as Jeremy Nicholl outlines on the Russian Photos Blog:

“Morel uploaded 13 images, of which 8 were infringed, and the maximum allowed per image is $150,000. There’s also the matter of AFP’s falsification of Morel’s copyright information, which allows for up to a further $25,000 in damages per image. So the maximum the jury can award against AFP is $1,400,000. For their part AFP previously asked in a court memorandum that if found guilty they should pay only $240,000. Whether that memorandum will even apply when the matter comes before the jury is unclear; what is now clear is that AFP’s final bill will be somewhere between a quarter of a million and one and a half million dollars, plus substantial legal costs.”

Just because staff can find a photo using PicFog, ThudIt, Twicsy or Twitcaps doesn’t mean the organization has the right to use it. Use it without permission, and the penalty could be substantial.

Add to the advice list: Train your staff so that they understand how to appropriately share and republish social media postings.

Web sites should start with the notion that if they cannot find a photographer’s contact info for a picture, it is unavailable for use.

— Glenn Fleishman (@GlennF) January 11, 2013

The most risk-adverse route for organizations: Use the “embed” code provided by Twitter or Twitpic to easily incorporate tweets in your story. In some cases, such as photos on pic.twitter.com and videos from YouTube, referenced media will automatically be displayed with the embedded tweet.

Twitpic provides embed code only for thumbnails, not full-size images; the code includes a link back to the Twitpic page and user account. There is an undocumented work-around, however, for displaying a larger image.

Alternatively, consider using Storify to curate a story using sources from multiple websites.

Advice for photographers

Same thing: Understand the terms of service on a web host before you upload your images. Almost all of the services make it clear that you have not relinquished your copyright in exchange for hosting.

It’s the license that you are granting the service in exchange for hosting that bears inspection.

When we visited this issue in 2011, Kraig Baker, an intellectual property attorney and adjunct professor at the University of Washington in Seattle, advised photographers to analyze three things when reviewing a license:

- the reach (are the licenses, global, non-exclusive, sublicensable?),

- the scope (how broad are the claimed rights) and

- any restrictions, such as a prohibition on commercial use.

My recommended host remains Flickr due to its variable licensing options (Creative Commons and traditional copyright) and its very clear statement of ownership and use:

“Photos and/or images found on Yahoo! Images or Flickr are the property of the users that posted them. Yahoo! cannot grant permission to use third party content. Please contact the user directly.”

However, Twitpic and MobyPictures — two micro-hosting services — also have restrictive (i.e., protective) licensing provisions. MobyPictures contains no licensing verbiage in its TOS. Instead, it explicitly prohibits commercial use without consent.

The Twitpic license covers content on Twitpic.com and affiliates. Like Twitter, Twitpic provides guidelines for anyone or any organization that wishes to reuse member content (emphasis added):

“All content uploaded to Twitpic is copyright the respective owners. The owners retain full rights to distribute their own work without prior consent from Twitpic. It is not acceptable to copy or save another user’s content from Twitpic and upload to other sites for redistribution and dissemination.”

Since Twitter began hosting images — first at PhotoBucket but now in-house — traffic at Twitpic has plummeted. However, Twitpic photos may still be displayed inline with tweets on Twitter.com.

What about larger photo-hosting services like Imgur, Instagram, Lockerz, PhotoBucket or yFrog?

Facebook bought Instagram in April 2012 and both companies recently updated their terms of service. After the purchase, Instagram’s traffic increased from less than 2 million unique visitors a day to more than 15 million in December, giving it more unique visitors than Flickr or PhotoBucket, according to Compete.

However, in December 2012, users objected to a TOS change implying that Instagram had a “perpetual right to sell users’ photographs without payment or notification.”

The company made a rapid about face, but there was fall-out.

The new Instagram TOS specifically addresses advertising but not how non-partners may use your content.

Expansive licensing is a hallmark of the big boys. For example, the Lockerz TOS contains a very broad license (emphasis added):

“Uses of the Submissions…. all such information you post, collect, or otherwise make available… (2) becomes publicly available such that it can be collected, viewed, redistributed, and used by others, including without limitation, on the Website and, more broadly, through the Internet and other media channels.”

If you want complete control over your images, avoid Photobucket. The license described in the Photobucket TOS explicitly allows for reproductive and derivative use without prior consent (emphasis added):

“If you make your Content public, you grant us a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license (with the right to sublicense) to copy, distribute, publicly perform (e.g., stream it), publicly display (e.g., post it elsewhere), reproduce and create derivative works from it (meaning things based on it), anywhere, whether in print or any kind of electronic version that exists now or later developed, for any purpose, including a commercial purpose. You are also giving other Users the right to copy, distribute, publicly perform, publicly display, reproduce and create derivative works from it via the Site or third party websites or applications (for example, via services allowing Users to order prints of Content or t-shirts and similar items containing Content, and via social media websites)”.

An exception to this trend is the Imgur TOS, which prohibits commercial use of someone else’s photos:

“By downloading a file or other content from the Imgur site, you agree that you will not use such file or other content except for personal, non-commercial purposes, and you may not claim any rights to such file or other content, except to the extent otherwise specifically provided in writing.”

Finally, yFrog. ImageShack operates yFrog and, unartfully, states that the yFrog license is restricted to the ImageShack network. Moreover, the service promises not to “not sell or distribute your content to third parties or affiliates without your permission.”

Photos on other sites

Photos, of course, are also shared on non-dedicated services like Facebook, Google+, Posterous and Tumblr. Are these licenses any more or less favorable to photographers?

Like Lockerz, the Facebook TOS and license is very broad. Facebook allows any public content to be used but does not define what it means by “use” (emphasis added):

“When you publish content or information using the Public setting, you are allowing everyone, including people off of Facebook, to access and use that information …”

Google limits the derivative works provision of its license to “adaptations or other changes we make so that your content works better with our Services.” However, “[t]his license continues even if you stop using our Services (for example, for a business listing you have added to Google Maps).” There is nothing explicit about how others might legally (or illegally) reuse your content.

Both Posterous and Tumblr have protective terms. The Posterous license is limited to the Posterous site. The Tumblr license limits sharing content: reblogging on Tumblr or sharing on approved third-party services.

If you believe your copyright has been violated, the American Society of Media Photographers has published a tutorial titled “What To Do If Your Work Is Infringed.”

TOS summary and site statistics

You can review a detailed comparison of the terms of service for 13 photo sharing sites or check out a summary table. Also, see statistics on unique visitors, as well as Alexa ratings, for the 13 sites discussed here.

The big picture

The web is a relatively young medium (two decades), but arguments about copyright infringement are centuries old. AFP v. Morel is not the only case — nor the first case — involving digital copyright questions. However, most cases have involved a different sort of infringement, one that involves DMCA take-down notices issued by corporations.

With quality cameras in almost every cell phone and easy push-button publishing to the world, the web is awash with digital images. The temptation to use the work of amateur photographers, particularly in breaking news events, will be hard for media organizations to resist.

Citizen journalists: Set up your YouTube account so that you can receive Google AdSense compensation. Set up your Flickr account to license your work via Getty Images for commercial use.

Media: Know the terms of service. Understand the difference between a promotional medium — tweets and Facebook status updates linking to an image — and hosting sites like Flickr, Instagram or Twitpic. When in doubt, use the Twitter embed code or an aggregation tool like Storify.

Finally, take Glenn Fleishman’s advice to heart: If you can’t identify and contact a photographer, don’t download and use the image to illustrate a story.

- The case is Agence France Presse v. Morel, U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, No. 10-02730.

- This is an update of Who Really Owns Your Photos in Social Media?, June 6, 2011

Kathy Gill (@kegill) has been online since the early 1990s, having discovered CompuServe before Marc Andreessen launched Mosaic at the University of Illinois in 1993. In 1995, she built and ran one of the first political candidate websites in Washington state. Gill then rode the dot-com boom as a communication consultant who could speak web, until the crash. In 2001, she began her fourth career as an academic, first teaching techies about communications and now teaching communicators about technology at the University of Washington. For almost five years, she covered politics for About.com; for three years, she covered agriculture.

Hey, great article. Thanks for the detailed references.

Nice!! VERY INFORMATIVE. Thanks!

WHO OWNS PHOTOS? ASK BILL GATES WITH CORBIS. THEY DESTROYED A FRENCH COMPANY CALLED SYGMA IN 2000. I WAS ONE VICTIM, EVEN JAILED, AND I CAN NEVER RETURN TO THE USA.

Jonah Peretti sounds like shard.