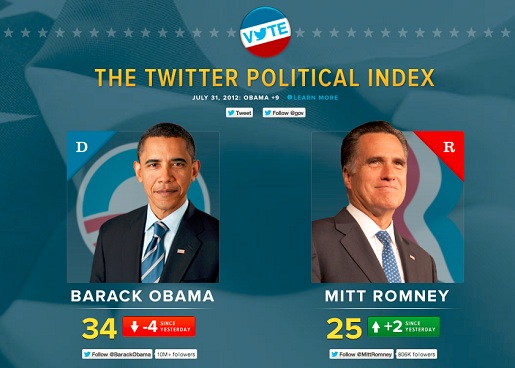

In the heat of this year’s U.S. presidential race, Twitter published a blog post announcing a new sentiment index meant to track and plot the tone of Twitter conversations about Mitt Romney and Barack Obama.

Under the headline “A new barometer for the election,” the post led off with some perspective: “One glance at the numbers, and it’s easy to see why pundits are already calling 2012 ‘the Twitter election.’ More tweets are sent every two days today than had ever been sent prior to Election Day 2008 — and Election Day 2008’s tweet volume represents only about six minutes of tweets today.”

The post then explained how the growth in tweet volume allowed Twitter to collect a massive amount of data, and how that data would be used, in conjunction with a few partners, to chart the feelings of Twitter users toward the candidates.

The index provided some useful insight in the mornings after convention speeches and debates, but its creation was meaningful in another way: It gave Twitter a vehicle to announce the important role it was playing in the election. Not only did the post not shy away from the term “Twitter election,” it was filled with facts — such as the one comparing Twitter’s 2008 and 2012 volume — meant to convey the magnitude of political activity taking place on the platform. Implicit was the message: Twitter was not a niche tool anymore. This was for real.

While there’s no denying the important role played by Twitter in the 2012 cycle, to call the 2012 election the “Twitter election,” is a bit of a reach. As a platform, Twitter is likely still just at the cusp of reaching its political potential.

Twitter’s Role in the 2012 Election

Twitter was a campaign messaging force during the 2012 election. Both campaigns built significant followings on the platform and deeply integrated their Twitter strategy with their core campaign strategy. When Obama coined the term “Romnesia” at a rally in October, for example, his campaign went to work getting the #Romnesia hashtag to trend on Twitter and including a link to a YouTube video of the speech in their tweet. By the time Election Day arrived, the speech had been viewed more than 500,000 times, and the hashtag became a standard inclusion in tweets favoring Obama.

Political operatives and reporters also glued themselves to Twitter. It was a place those covering the campaign could not afford to ignore and, as a result,“winning the Twitter battle” became a obsession among the campaigns’ communications teams. Win there, the thinking went, and your perspective would win out on TV, in print and the rest of the web. Perhaps because of these high stakes, it was not uncommon to see communications folks from both sides battle via @reply.

<a href="https://twitter.com/timodc">timodc</a>samsteinhp Your anemic follower count belies your claims of being a twitter “celebrity”.— Lis Smith (@Lis_Smith) November 6, 2012

Individuals also used Twitter to influence the political conversation from the outside. Twitter’s flat and democratic nature — replies all aggregate in the same place -- allowed political outsiders to insert their thoughts into the consciousness of those on the inside. This meant an account like Sean Hannity's Hair ("shannityshair”:https://twitter.com/SHannitysHair), a biting, ferocious political feed run by an anonymous Romney supporter, was able to solicit frequent responses from media personalities (including Sean Hannity) and even got a follow from Obama’s director of rapid response, Lis Smith. Without Twitter, there’s a good chance “Hair,” would have been a small-time blogger and local bar ranter. Instead, he sort of had a seat at the table.

The fact that Twitter brought these conversations — that may once have occurred via email, or at a coffee shop, kitchen table, or bar — into the open, is a major part why Twitter’s head of Government, News and Social Innovation, Adam Sharp, describes Twitter as the “new town square.” According to Sharp, Twitter has become a central place for communities to get closer to each other, the candidates they support, and the issues they care about.

Room to Grow

While there’s no denying Twitter’s impact on the 2012 election, there is still a good amount of potential the platform has yet to reach. To begin with, if Twitter is the new town square, then notably absent from it over the course of the election were the campaign accounts themselves. In the 2012 election, @BarackObama and @MittRomney functioned primarily as one-way communication tools instead of two-way conversation participants. Scroll through the accounts’ pre-November 6 tweets, and you will see a lot of quotes, photos and links back to campaign websites, but a dearth of @replies, meaning that the campaigns decided largely not to use one of Twitter’s most important features.

Also, to be a town square, you first need be in a town. Pew’s latest study on Twitter usage found that only about 15 percent of Americans use Twitter and daily users are at about half of that, or 8 percent. That is not meant to belittle Twitter’s impact — in fact, it probably makes what took place on the platform more impressive — but rather to show that there’s room to grow.

Finally, advertising opportunities during the 2012 election remained rather basic. Campaigns could pay for promoted trends and tweets, and did so regularly. But, Twitter is still figuring out its monetization strategy, so what we saw in 2012 is most likely the tip of the iceberg in regard to the type of exposure campaigns may soon be able to pay for on the platform.

What the Future May Hold

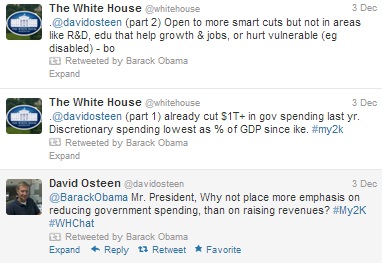

For its part, political activity on Twitter seems to be moving in the right direction. Calling in from Tokyo for a phone interview this past Thursday night, Twitter’s Sharp spoke enthusiastically about what happens when politicians engage with their constituents and potential voters on the platform. Sharp referenced President Obama’s fiscal cliff Twitter chat last week in which, over the course of 44 minutes, the president took eight questions, retweeting them first and then @replying with an answer.

“Imagine someone on the other end,” Sharp said. “Maybe they’re waiting for the bus or going through the supermarket and they ask a question, then they get an answer and see video of the president on a laptop considering and typing. That I think is a very profound image.”

The chat was not the first time Obama took questions on Twitter, but Sharp said he expects future campaigns to feature more of this type of engagement as politicians grow more familiar with it. “In the scale of political discourse, Twitter is still a relatively new tool for candidates and elected officials,” he said. “But the momentum is certainly pointing in the direction of greater engagement now that they have seen the benefits to both candidates and voters over the cycle.”

In future campaigns, Twitter’s ad experience will likely be very different as well. As noted by BuzzFeed’s Matt Buchanan, Twitter is moving towards a more visual experience, one that may eventually include tweets with pre-expanded photos and videos appearing in users’ timelines. This sort of experience is already starting to appear in Twitter’s Search and Discover sections, so it wouldn’t be surprising to see future campaigns’ YouTube ads sitting above a set of search results, or at the top of users’ timelines, already expanded and set to play. The ad unit could be a powerful one for campaigns seeking more visible ways to engage with Twitter’s audience.

Twitter is likely hoping these changes will bring more users into the platform. Sharp explained that the changes made so far are meant to help people discover the magic of Twitter, and that the experimentation will continue. Whether it’s through these tweaks, or simple organic growth occurring over time, Twitter looks poised to push past the 15 percent adoption number and fully develop into the bustling town square described by Sharp.

Building on Data

As Twitter’s user base grows, it will also be able to do increasingly complex things with its data, which could get especially interesting when it comes to politics. Jason Stein, founder of New York-based social media agency Laundry Service explained in a phone interview that he thinks the next iteration of Twitter’s sentiment index could be a state-by-state map, with predictions for which candidate is in the lead. “I think that Twitter can be predictive of the outcome of the election if there were a lot more people on it,” Stein said. “I think that Twitter will be able to mine that data to tell you where things are going with the election based on what people are saying about candidates.”

While not going this far, Sharp did say that during the 2012 election, when a candidate would mention coal, Twitter would see bursts of engagement in places like West Virginia, Western Pennsylvania and Montana. Indeed, as more users sign up, Twitter will have plenty of options regarding how to use the politics-related data including, potentially, selling it to the campaigns.

It’s easy to understand why some people watching the 2012 election unfold on Twitter would jump to call it the “Twitter election.” Twitter provided an exciting, new participatory way to experience presidential politics on its scale that had not been seen before. Still, for the time being, let’s put the term on ice. If the momentum continues, and there’s reason to think it will, we’ll need it fresh for a time perhaps not too far in the future.

Alex Kantrowitz covers the digital marketing side of politics for Forbes.com and PBS MediaShift. His writing has previously appeared in Fortune and the New York Times’ Local Blog. Follow Alex on Twitter at @Kantrowitz.