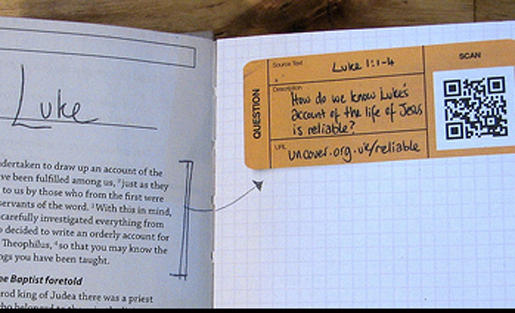

A few weeks ago, I received a fascinating package in the mail. It was a copy of the gospel of Luke interleaved with graph paper and QR codes.

Uncover, designed and printed by UCCF: The Christian Unions, is a digital campaign within a well-established tradition of gospel distribution that goes back to the 19th century. U.K. Christian Unions hold annual “missions,” week-long campaigns involving extensive PR and talks from notable Christian speakers. Students also coordinate semi-formal gatherings ranging from Q&A pub nights to dinner invitations with friends. The distribution of gospels always supports a broader initiative to highlight Christianity, answer questions, and encourage students to join the faith. UCCF currently supports several hundred Christian Unions throughout the U.K.

The QR codes in Uncover link to videos like this one by Cambridge theologian Peter Williams. Many of the videos are short arguments by notable Christian academics. Others are direct appeals to respond personally to the claims of Christianity. The text is also interleaved with lined note paper that sometimes features rhetorical questions printed in a handwriting font. “It’s time for forgiveness to be offered to the world. Will we receive it?” the notes ask.

Fascinated by the design, I called up Pod Bhogal, head of communications for UCCF, to ask what they hope to achieve with Uncover.

Here are some key insights from our conversation:

- Students aren’t used to reading long texts, Bhogal tells me. The Uncover digital campaign was designed to drive engagement to the printed text and to conversation with friends over time. These goals are derived from UCCF’s view that people become Christians primarily through an encounter with Jesus via the text of the gospels. Bhogal sees the activity around a mission as helpful context and support for this encounter.

- Bhogal offers what he hopes will be a common encounter with Uncover. He wants people to open the front cover, read the first page, watch the first video, and then choose to read further.

- The hardcover design was a radical departure. UCCF typically prints 400,000 gospels every few years. Uncover, which has been printed in much smaller numbers, is “a gift with higher perceived value.” Its physical design more clearly expresses the degree to which Christians value their foundational texts — and the friends they give them to.

- Undergraduate Christians are still exploring their own faith and may feel unprepared to speak with people who don’t share their beliefs. To facilitate semi-formal peer conversations about the gospel of Luke, UCCF has published a companion workbook by Rebecca Manley Pippert.

- In a recent video, Pippert asks what success means for this campaign.

Reviewing Uncover

I made the infographic below to show the information architecture of Uncover. Light brown hexagons are the chapters of Luke’s gospel. Orange speech bubbles represent annotations. Diamonds represent online QR code content. Green diamonds are special full-page video links:

The supplementary material to Uncover answers common questions about Christianity and poses questions of its own, encouraging readers to consider their own lives in response to the text. For example, a note attached to Luke’s account of the Temptation of Christ asks, “Will he trust his Father or will he be like Adam and do his own thing?” Two pages at the end offer a concise summary of Christian teaching and invite the reader to pray to become a follower of Jesus.

There are two different kinds of video links. Curiously, the sections labeled “Evidence” (green diamonds) are a six-part sermon in three-minute segments, connecting the text with a personal appeal to consider Christianity. “Jesus didn’t die without effect. He died so that through him we could come back into to a relationship with God. Do you know his love?” the college-age speaker asks at the end.

A parallel track of more self-contained videos (black diamonds) features prominent men and women Christian academics answering common questions about Christianity as they arise in Luke: the provenance of the text, the plausibility of miracles, the problem of suffering, the claim that Jesus is the only way to God, faith and reason, morality and salvation, and the resurrection.

Does this text meet the goals of its designers? I think so. As a collection of story, argument, teaching, and poetry, the Bible is not something to read in a linear fashion. Uncover is the first transmedia text I’ve seen which presents the multiple layers of voices experienced within Christianity. Uncover also makes a fair call to action at the end, with more room for nuance and disagreement than most digital campaigns. Its annotations are very direct, but there is only one per chapter, and the blank pages give readers ample space to question and disagree, and develop their own conclusions.

I asked Bhogal in our interview why the cover of Uncover offers no indication of what’s inside. Doesn’t that lack integrity? Might people be upset if their friends offer them a free notebook only to discover that it’s religious propaganda? Ambiguous covers are a longtime UCCF practice, and Bhogal responded that many people are put off by religious texts. They may feel uncomfortable carrying one around. “We wanted a gospel that was student friendly,” he said.

Access is another concern. QR codes send a clear visual signal that Uncover offers online interaction with the text. Next to each code is a printed web address, so scanning isn’t necessary. Does anyone use QR Codes? Two-fifths of U.K. adults own a smartphone, according to OFCOM, the U.K.‘s independent regulator. Only 40% of those accounts have data plans, and even fewer have the bandwidth for video. That said, computers are now a basic requirement at universities, and most have good bandwidth. If broader Christian groups want to adopt Uncover, it will need to be much more accessible.

Inviting Conversation

Despite its role in university missions, Uncover’s digital presence doesn’t invite conversation. I would love to see a version which facilitates a digital conversation between the reader and the person who gave the book. Platforms like Reading and Readmill have already made reading social. For religious conversations, it might also be possible to draw lessons from more intimate social apps like Path and Pair, or even encourage conversation over SMS. Social conversation technologies like Branch make it possible to bring in new voices when needed.

Christian Engagement Metrics

Since Uncover is online, UCCF can now access data on which QR codes and web pages are most popular over time. When I asked Bhogal about data collection, he said they didn’t have the capacity to incorporate analytics into their campaign. If they had, UCCF could have developed a dashboard for individual university groups to see how many people in their region are opening the Bibles, scanning the codes, and watching the videos. As university groups plan their mission, they could have chosen topics to match the most common questions.

Update (Nov 29, 11:40am EST): Pod writes, “We have incorporated analytics in that we monitor how data is accessed (QR code or desktop), how much data is accessed (page views), how many people access data (unique visits), etc.”

Religious publishers are already doing fascinating work to track engagement with texts. Crossway has visualized Bible reading plans. Biblegateway has posted a beautiful dataviz of how people share and read the Bible, the 100 most popular verses, and the most searched-for verses. (I would love to compare this by region.)

For the most personalized experience, UCCF could have printed unique codes into every individual gospel, tracking the unique reading experience of every printed copy. This kind of data analysis is standard practice in the e-book industry. As Christianity moves into the space of digital texts, we will need to make informed, ethical decisions about data protection and privacy. U.S. presidential campaigns used big data and behavioral experiments to convince voters and get them to the polls. MoveOn sent voters personalized voting record postcards with data on their voting record and their neighborhood average. Will religions do the same? (For more on e-book surveillance, read this pro and con in the Guardian. See also Zeynep Tufekci’s New York Times article, “Beware the Smart Campaign.”)

Online activity also makes it possible to track religions from the outside. What might religion transparency data look like? After I created a data visualization comparing sermons across cultures, Brian Keegan pointed out research by Miya Woolfalk which analyzes political language in sermon text across 21,000 sermons and 2,100 clergy in the U.S.

While engagement data may someday become as common to religious outreach as political campaigns, the larger goals of Christian outreach might also slip people’s grasp: love, understanding and empathy.

What do you think? Tell us in the comments.

Nathan develops technologies for media analytics, community information, and creative learning at the MIT Center for Civic Media, where he is a Research Assistant. Before MIT, Nathan worked in UK startups, developing technologies used by millions of people worldwide. He also helped start the Ministry of Stories, a creative writing center in East London. Nathan was a Davies-Jackson Scholar at the University of Cambridge from 2006-2008.

A version of this post originally appeared on the MIT Center for Civic Media’s blog.