There are no winners in the mess at the Red & Black. But there are lessons.

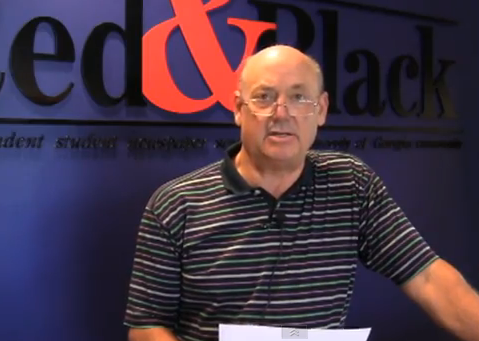

The Red & Black at the University of Georgia has long been regarded as one of America’s finest college news operations. The students’ journalism is consistently first class, and publisher Harry Montevideo has a track record as one of the sharpest business minds in the industry. (Disclosure: Montevideo has been a mentor of mine.)

But last week, a clumsy board memo became public, suggesting students focus more on “good” stories and granted more editorial control to professionals. Student editors resigned in protest. And Montevideo scuffled with a reporter at an open house. Montevideo has since issued a written apology for the scuffle and the board member who wrote the memo has resigned.

How could things go so wrong? And what can the rest of us who work in college newspapers learn from it?

On the face of it, the dispute rests on whether students or professionals “control” the editorial content. Certainly, student control is central to the mission of student media. But the reality of running an independent, self-supporting college newspaper in the digital age is more nuanced than just who controls content.

Boards, editors and publishers must figure out how to evolve from the 1990s model of a journalism lab funded by an advertising monopoly to a 2010s model of a media company fighting in a hyper-competitive market.

“Every paper in the country wrestles with that: How do we deliver what you need to know vs. what you want to know?” said Barry Hollander, a professor at the University of Georgia’s Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication.

“If I knew the answer, I’d be a consultant … I have no idea what the answer is, and I have my doubts about anyone who says they know what the answer is. We’re all trying to feel our way along.”

From lab to business

College newspaper boards and publishers must figure out the business model while still giving students the editorial freedom that they deserve and without compromising traditional journalistic values and ethics. In some ways, it’s a more complicated balance than professional newsrooms where the publisher and owners get the final say on all business and editorial decisions.

In the 1990s model, college newspapers offered students and advertisers the only option for news and a local marketplace. That opened up a river of revenue that subsidized student-led newsrooms and provided nearly limitless journalistic freedom. I was a product of that system at the Oregon Daily Emerald at the University of Oregon in the late 1990s. It was the most fun I’ve had in journalism.

But I will be the first to admit, we occasionally produced some silly, unprofessional and self-absorbed journalism. In that model, it didn’t matter. We practiced the skills we learned in class — writing, sourcing and beats — and didn’t have to bother with advertisers, rates and readership.

But those days ended long before Myspace.

In the 2010s model, college newspapers offer one option among dozens. They compete against Facebook, Google and Twitter for students’ time and advertisers’ money. For many newspapers, readership and revenue are down 25 percent or more from the peak in the 1990s or 2000s.

Boards and publishers stare at those trendlines and seek solutions. But they also know they have no direct control over the most important piece of the operation: the content.

Different models at different schools

Each independent college newspaper confronts that challenge differently.

“It’s the same as it has always been: education, training, persuading, suggesting. Some combination of all of those things,” said Eric Jacobs, general manager for 31 years at The Daily Pennsylvanian.

At the Red & Black, the board believed the newspaper needed more professional oversight, especially online. “You’ve got to have people there to guide these things,” Elliott Brack, the board’s president, told the Student Press Law Center. “Each one of those takes its own professional.”

But the students believed they were being forced into assignments that were more public relations than newsgathering, including “grip and grin” photos during sorority rush week, said Evan Stichler, the Red & Black’s former chief photographer. “I think they were looking at it more from the marketing and advertising standpoint of getting viewers,” he said.

At UCLA’s Daily Bruin, director Arvli Ward is building a digital advertising network completely divorced from the newspaper. So far, his staff has built 60 mobile apps. His goal: to generate enough advertising revenue to subsidize the student newsroom.

“The monopoly that we owned was not on distributing dead tree products around campus, it was the advertising monopoly,” Ward said. “That’s what we have to regain. When we regain that, we can funnel money to our newsroom and let students do what they do. It’s not going to be The New York Times, and sometimes it’s going to be off color, but that’s what makes a college newspaper interesting.”

At the University of Oregon’s Emerald, where I now work again, our student editors went on strike in 2009.

Students walked out after a consultant to the board drafted an organizational chart in which the publisher would oversee the student editor. I advocated for and later chaired an Editorial Independence Committee to protect the newsroom’s editorial independence.

But my perspective evolved when I became publisher of the Emerald and was accountable for the company’s financial performance. I still believe that students must retain editorial control. However, I also see the need to ensure student editors run the newsroom in a way that fits with the company’s long-term business goals. It’s a delicate balance that is now reviewed at least annually by an Editorial Advisory Committee led by a former Emerald editor in chief and editor at The Oregonian.

The sense of urgency is intense for independent college newspapers. Now, more than ever, college newspapers need tighter working relationships among news editors, business leaders and board members.

Or as Stichler, the former Red & Black photographer, put it: “Stick to your principles. Have some standards between board, editor and staff people … You have to make sure everyone is in agreement.”

Update, Tuesday, Sept. 21:

In a statement Monday, the board announced it had re-instated Editor-in-Chief Polina Marinova and Managing Editor Julia Carpenter.

A second board member, Charles Russell of Atlanta, has also resigned and said in a statement: “I cannot in my mind — and will not in my heart — be a party to what you are about to do as a board today.”

Ryan Frank is president of the Emerald Media Group, formerly the Oregon Daily Emerald, the independent nonprofit media company at the University of Oregon. He blogs at thegarage.dailyemerald.com.