“The Republia Times” generated a significant amount of buzz when it was released a few weeks ago, even though it was developed by Lucas Pope simply as a warmup for a 48-hour game competition.

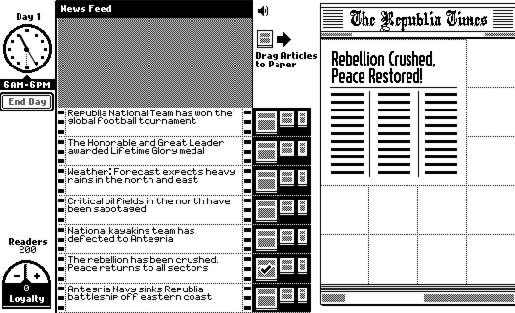

It’s a brilliant little game about tabloid, censorship and propaganda in a war-torn nation. It’s also a tidy reflection on the cyclicality of time and the news machine. Your initial goal as the editor of a state-run newspaper is simple: Raise readership and loyalty for a transitional government by carefully selecting stories from the news wire. Based on your performance, you receive a concise, daily report on the well-being of your captive family.

If you haven’t played it yet, you should do so before reading further; I’ll be getting a little spoiler-y, because the game has been out long enough to comfortably comment on its twists and curiosities.

your job as editor-in-chief

What’s most evocative about this game for me is how little many of the potential articles have to do with politics as we usually think of them. We’re told, as if we already didn’t know, that a good way to grow readership is to include pieces about sports, entertainment and the weather. This is business-as-usual for any newspaper, even a serious and honest endeavor. While the sporting and celebrity news in Republia regularly have political content, like the defection of a sports team to a rival nation, the weather is where the selection of content hit hardest for me.

At one point, I found myself asking whether or not it was a good idea to tell people that it was going to be rainy tomorrow. And on days where the random draw of stories is unlucky, I giggled while printing a page bearing nothing more than the fact that it’s a warm and sunny day. It’s not until the fourth day that the game cleverly tells us that bad weather will not affect the loyalty of citizens, because “the government cannot control the weather yet.” Little touches like this embellish its bare-bones concept (because, really, when was the last time you grinned after reading a tool tip?).

The layout of the page is rather strange, perhaps more reflective of the history of videogame design than it is of print. The hard cap on the size and number of stories that can fit on a page remind me of the 2D “Final Fantasy” games, where the randomized encounter system has to select carefully between enemies based on their strengths and the amount of tile space occupied by their pixel art. This presents something of an anachronistic feel to the game, because it’s hard to imagine a crummy contemporary newspaper without lots of pictures, graphs, and layout tricks; but this simplicity suits the restricted nature of the game’s rapid development.

“Republia Times” uses a “bank” of stories. In a world where there are a multiplicity of news sources, it would be absurd to store days-old news in a bank to be used whenever it was convenient. Yet this makes perfect sense in a single-channel system, and it’s also an efficient way to store the stories programmatically. This banking is what makes the game so easy to play, as most commentators have noted; basically, ignoring the less desirable political stories over the course of the first few days ensures that the player will be able to pump up anti-government sentiment once she has been contacted by the Resistance. It’s a brilliant way of creating the impression of a wide possibility space while constraining the game’s conclusion for a majority of players.

Another thing I like about “Republia Times” is that it contextualizes quitting in a way that most games can’t really pull off expressively. If you think about a traditional goal-based game, turning the game off after a number of failed attempts to reach the next checkpoint just “freezes” your character and its progress right there in the save file. There’s no concept of what’s happening to the character while you’re away. This is even more strange in the case of persistent online worlds, where the only real explanation for your absence is that your avatar is “sleeping” or “traveling outside the realm” (sometimes for months on end).

the ‘rhetoric of failure’

But in the case of political game design, we can return again to Ian Bogost’s idea of the “rhetoric of failure.” This rhetoric is seen in games where the only way to “win” is to not play the game in the first place, like in “September 12th,” where attacking the terrorists only leads to their multiplication. Usually this has only a conceptual significance. However, “Republia Times” presents us with a tidy fictional context for the act of abdicating the controller.

Throughout the game, we see stories of celebrities and sports figures defecting from Republia for greener pastures. The only thing keeping the player in Republia, really, is this idea that one’s family is being held captive. But, after the game’s twist ending, it just makes sense to turn the game off immediately, thus leaving the country.

“Republia Times” stands more as a mental exercise than it does as a dramatic or even contemporary culture commentary piece. There is, for instance, no counter-propaganda machine interfering with your work, and the brief textual reports on your family aren’t as powerful as pictures of them would be.

It’s hard to classify this as any proper type of newsgame, whether that be an editorial game or a literacy-building game. But it’s easy to imagine it as a successful prototype for a more thorough critique of the propaganda model of contemporary news media — or even as the basis of a competitive multiplayer game about the risks and rewards of toeing the party line in a media ecology where there’s more than one news source.

Great article