Last July, a high-speed train crashed in the Wenzhou suburbs of China’s Zhejiang Province, killing 38 people and injuring 192. The Chinese government’s media apparatus quickly swung into gear, working overtime to quell growing rumors of an engineering flaw that may have caused the crash. But despite the Chinese Communist Party’s attempt at full control over China’s media outlets — ordering that newspapers avoid mentioning the crash at all, except to spotlight “positive news or information released by the authorities” — the anguish and grief of the Chinese people would not be silenced, as they took to social media outlets to demand answers from the authorities.

Some two months later, two of the boldest and most popular newspapers — the Beijing News and Beijing Times — were taken over by Beijing’s propaganda department in yet another round of the Chinese government’s ongoing game of “media whack-a-mole” to suppress voices of dissent. And again, social media provided an outlet for the people, creating a completely different narrative for the news.

These are just two of many examples, from the Arab Spring to Japan’s tsunami and nuclear aftermath, that highlight the juxtaposition of global news in the digital age, both raising and answering questions about how to cover news about regions that may be largely characterized by airtight official control. The news is the news, but how can the new new journalism cover the subthemes of grassroots dissent and provide an unfiltered examination of events around the world? Are they separate stories, or does the tension between the two create the overriding central story?

Today, the boundaries between legacy TV broadcasting and digital native news are increasingly blurred as the convergence age continues to develop new tools for storytelling, curation and advancing different perspectives. It’s possible for media startups and scrappy independents to tell multi-layered stories with digital tools — but navigating the new territory is complex, challenging work, despite the number of tools that are available. Here’s a backstage look deep into the anatomy of one hybrid/digital native program that’s attempting to build and learn from a new model, adapting along the way.

A Transmedia Global News Model

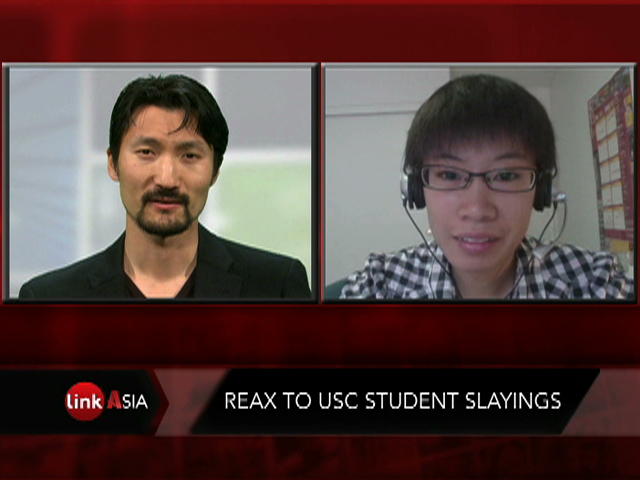

For the past year, Link TV, the non-profit independent satellite broadcaster and digital media organization, has taken on these questions of blurred boundaries with LinkAsia, a weekly news and culture digital/broadcast hybrid program about life, culture and technology in Asia (for which I’m part of the producing team located in Washington, D.C.). Hosted by Yul Kwon (winner of “Survivor” and host of PBS’ “America Revealed”), the show’s formula is founded on old-school broadcast journalism but dressed up and brought to transmedia life through a mashup of some of the most promising bells and whistles of the digital journalism revolution. We curate. We mine social media perspectives. We host citizen journalist contributors around the world and in the U.S. And we translate social media chatter from voices on the ground in China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam.

Global Voices Online + Storify + Skype + Exclusive Content = Digital News Mashup

In a hybrid model on multiple levels, the show’s producers — led by George Lewinski, former senior editor at PRI’s “The World” and foreign editor at NPR’s Marketplace — curate the news of the week through the eyes and ears of citizen journalists on the ground in Asia, combined with exclusive syndicated packages of official news from Asian nations’ commercial and state-run TV networks, a list that notably includes CCTV (China), NHK (Japan), MBC (Korea), NDTV (India), and VTV4 (Vietnam).

A team of producers based in San Francisco monitors and translates social media chatter in Asia, and on-the-ground correspondent reporting comes from a partnership with Global Voices Online. Show wraps from Yul Kwon are produced in Washington, D.C. (at American University’s School of Communication), and Global Voices Online correspondents and other expert contributors unpackage and analyze the news via Skype from China, Japan, India, Pakistan, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam.

The LinkAsia blog includes regular Storify features, with a digital team that curates social media-generated blog posts from both U.S. and Asian social media sites, including Sina Weibo, to publish and continue to follow stories on multiple platforms. And then all of this content — from original reporting on the ground to exclusive content from Asian broadcasters to grassroots voices via “in country” social media — is packaged into both half-hour complete broadcast episodes and viral-sized bits of news hosted and promoted via the LinkAsia digital properties, including the @LinkAsiaNews Twitter feed, Facebook page and website, which streams the show and ongoing coverage.

New Narratives, Not Just New Distribution

Almost a year since the project’s launch, the big discovery is that the digital tools have not only enhanced the journalism, but they have completely changed the content of stories — not just the distribution.

A show that started out as a weekly chronicle of politics and business in Asia, created for a U.S. audience — fed from syndicated news packages from Asian nations — is a full, nuanced ongoing examination of life as it is experienced by people who live there, juxtaposed with the “official portrait” of that life by the region’s official media organizations. It’s the gap between the two that has created and supported the most valuable reporting and analysis — and the digital tools that allow us to continue to follow the long tail of the story after it may have faded from immediacy.

A notable example was the news around the death of North Korea’s Kim Jong-Il, reported by virtually every news outlet in the world. Thanks to Link TV’s syndication deal with South Korea’s MBC, the LinkAsia team was able to track the story as it was being reported in Korea, not filtered by U.S. reports. The team packaged up and translated MBC stories as they happened, scoured and translated Korean social media sites for the perspectives of people on the ground, folded in citizen journalist perspectives in South Korea, and then packaged all of this up into one or two stories per day, following developments as they happened. The digital tools directly enabled the team to offer an unfiltered examination of the news and the voices of the people on the ground. We called these digital news packages LinkAsia Bulletins, and they were able to cover a story in a deeply multi-dimensional way, far beyond the confines of a broadcast half-hour.

Similarly, Storify has become an invaluable part of the approach, particularly since the team translates directly from social media sites in the countries on which we’re reporting. In the case of the ongoing fallout from Japan’s 2011 earthquake and tsunami — and the continuing developments from the Fukishima nuclear plant — the digital team has been able to stay on top of the ongoing scenario there, drawing from social media and reporting around the world.

Spreading the Word

The challenge facing the program, as with other independents and non-profit sources of news, is attracting audiences without a paid advertising budget — getting people to watch, embed and pass along the content. So-called legacy tactics for promotion are still important — getting the word out through sophisticated promotion and advertising — while digital tactics are crucial, like embedding content in blogs, social media outreach, organic discovery of news content, and sharing across digital platforms.

But for non-profit and indie media without lucrative marketing budgets, it’s a challenge that requires extra creative thinking. For our part, we’re reaching out to audiences who might be most directly interested in a unique approach to news from the region, including universities, but also concentrating on partnerships that translate into digital word-of-mouth and an organic discovery of the project.

It’s hardly revelatory to note that regions of the world are more intertwined than ever before — or that digital tools are transforming journalism and shaping the habits of younger news consumers. But in the example of digital-hybrid LinkAsia and many other players in the new journalism ecosystem, it’s the ability to report on the media filter itself — by sharing perspectives that aren’t filtered — that might be the most exciting and promising development of all.

Caty Borum Chattoo is Executive in Residence at American University’s School of Communication in Washington, D.C., and studio producer of “LinkAsia,” produced by non-profit independent broadcaster and digital media company, Link Media, Inc., at the American University School of Communication’s Media Production Center. A documentary producer, media strategist, and Huffington Post contributor, she holds a master’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School of Communication. Follow her on Twitter @CatyBC.