Facebook’s impending stock offering has rekindled laments about the ills of social media. They largely miss the mark.

The toppling of dictators, strengthened familial connections, rebirth of friendships, fanning of imagination, and creation of new methods of sharing — to these I can add some very personal examples of how social media have helped me.

To the whiners, though, the glass is well more than half-empty.

Author Jonathan Franzen’s complaints were resurrected in a recent episode of “On the Media” dedicated to Facebook. Franzen’s famous quote came up in an interview with writer Paul Ford. Friending someone, Franzen has said, “is merely to include the person in our private hall of flattering mirrors.”

The show talked of unwanted sharing of our info, difficult privacy settings, the futility of trying to delete embarrassing content, and ways the service clandestinely tracks web surfing.

Demanding Attention?

The “On The Media” show also cited the essay by New York Times editor Bill Keller that got a lot of vigorous comments — some on the story’s web page — both for getting it “right” and being rather “lacking.” Keller’s piece bemoans social media as “aggressive distractions,” and says Twitter “demands attention and response.”

But Twitter doesn’t “demand” our presence. I am perfectly capable of shutting off TweetDeck while I write this column. I look at my personal Facebook page every few days when the spirit moves me, not when my “wall” tells me to.

Keller griped how “Facebook friendship and Twitter chatter are displacing real rapport and real conversation, just as Gutenberg’s device [the printing press] displaced remembering,” though he did allow that he wouldn’t give up his books.

Perhaps.

But they can also lead to real connections. When I tweeted about a reading I was preparing for a course, one of the book’s authors, based in Thailand, got in touch. We’re now friendly, my students have “met” him via video chat, and he and I have shared phone calls and a meal at a New York deli.

Through Facebook I learned of a junior high school reunion that let me reconnect with dear old friends. We hugged, laughed and shared food and drink, and will probably do so again.

A Facebook page I put up let former colleagues and I in different geographies share memories of our late friend, New York Times reporter Anthony Shadid.

The service also lets me better stay in touch with my sister and stepmother, both of whom live airplane rides away.

And, yes, social media have benefited my business, as well, helping attract many thousands of people to web pages, white papers and events, and bringing in more money at less cost than without them.

A recent Pew Center survey found that few Facebook and Twitter users learn about campaigns or candidates through those media. I’d answer by pointing out the Barack Obama and Mitt Romney campaigns’ intense data mining of social media that could help put either over the top in elections.

Sounds Like The Web, Again

The complainers’ tone, if not their vocabulary, reminds me of colleagues who scoffed that the masses would never find the web truly useful.

When I interviewed Ray Bradbury in 1996, he called the Internet a bunch of commercialized “hooey” and asked me to name “one good thing” it had done that didn’t involve money.

I told America’s lion of futuristic fiction that a search for my name had turned up an article by a satellite technician in Argentina, and that I had emailed him to ask why we shared our unusual last name.

Within months, he and his wife visited my family in New York. I was reconnected with a branch of our family my father had lost track of two decades earlier during Argentina’s troubled times.

I could have told Bradbury how, living in Japan during a Fulbright fellowship in 1992, I was able to connect via a listserv email discussion group with about 130 Japan scholars around the world, including some luminaries it would have been harder to reach through more traditional means, let alone conduct an international time-shifted discussion.

I might have mentioned how my stepfather and I were able to “chat” very inexpensively while I was overseas.

When Keller wrote that Twitter makes smart people “sound stupid,” he seemed to miss the pithy humor of the “Nuh-uh” reply to his “#twittermakesyoustupid discuss” tweet. Twitter was, by the way, my first and only alert that Keller had written his essay.

Social media are modes of communication, with their own grammar. Far from destroying intelligence, they demand a certain deftness and nuance. Learning them can force us to stretch, akin to learning a new language.

Social Media Can Build or Destroy

They are also tools that, like a hammer, can be used to build or to destroy. They amplify our best and our worst.

Social media and the web have changed my life for the better, because I have let them do so, been open to the wonders they can let me experience. When some effluvia waft in, I try to tolerate them and concentrate on the better parts of the stream, while knowing it’s far from perfect.

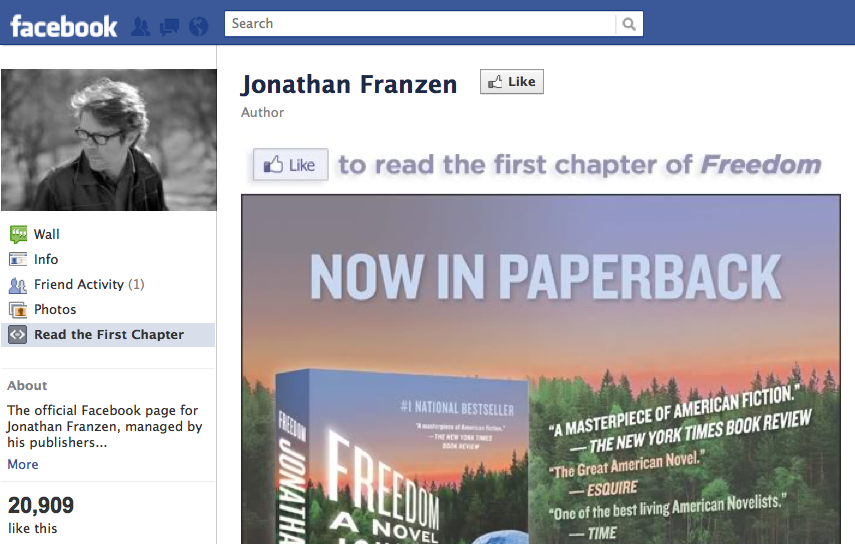

I hate having to “like” Facebook pages I may not actually feel that way about in order to see what’s in them. Ironically, a chapter of Franzen’s book “Freedom“ is among the examples. As Franzen wrote, “If you succeed in manipulating other people into liking you, it will be hard not to feel, at some level, contempt” for them.

I am also irritated by the LIFO framework in which the most recent missive goes atop ones that may be more important, and sick of spam messages on Twitter and everywhere else.

Yet, to rail that social media destroy our social fabric is as silly as claiming that books destroy our memory. Albert Einstein and many others have chosen to not use their memories for things they can easily look up.

“If you don’t have [Facebook], you’re now actively at a disadvantage in large parts of society,” scholar Clay Shirky said in the “On the Media” Facebook episode. “There will never now not be a period where most human beings on the planet are connected to the same grid.”

He’s right. Rather than rebel, we ought to learn to use the tools to our benefit. And were Shirky talking to my face, I’d put my widescreen smartphone down, look in his eyes, and give him my undivided real-time attention.

An award-winning former managing editor at ABCNews.com and an MBA (with honors), Dorian Benkoil handles marketing and sales strategies for MediaShift, and is the business columnist for the site. He is SVP at Teeming Media, a strategic media consultancy focused on attracting, engaging, and activating communities through digital media. He tweets at @dbenk and you can Circle him on Google+.