Education content is sponsored by the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism, which offers an intensive, cutting edge, three semester Master of Arts in Journalism; a unique one semester Advanced Certificate in Entrepreneurial Journalism; and the CUNY J-Camp series of Continuing Professional Development workshops focused on emerging trends and skill sets in the industry.

This piece was co-written by Alexa Capeloto.

As if taking their cues from an entertainment industry increasingly inclined to remake just about anything from the ’80s, today’s college students seem to be jumping into a collective Hot Tub Time Machine.

We watch as our journalism students covet Atari, combat boots, Star Wars and other throwbacks as if they discovered them. (We actually had a turf war with a few of them over Nirvana not too long ago.)

But a pre-computer newsroom? Who in their right mind would produce a student newspaper without writing or editing on a screen? Without email or the web for research? Without digital cameras or software for photo editing and layout?

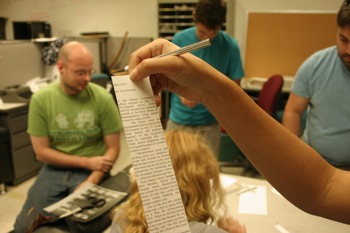

Defying progress and (to the minds of some observers) logic, a group of student journalists at Florida Atlantic University actually decided to give old-school production a try. Led by volunteer adviser Michael Koretzky, they published the final summer issue of their newspaper, the University Press, without technology. You can see the results here.

The project, called All on Paper, incited some controversy among journalism educators in the weeks after, with the main critique being, “What’s the point?” And only three schools have taken Koretzky up on his offer to help replicate the decidedly retro experiment on their campuses.

But the lessons Koretzky’s students learned, and the way their work changed as a result, convinced us that the project is worth defending and repeating.

How it began

Koretzky hatched the idea after having a conversation any veteran journalist knows well. He told students he used to do all the work they do, but without computers.

“Yeah sure Koretzky, no computers.”

“No really! NO computers.”

They marveled at what that must have been like.

He decided to show them.

With a $750 grant from the Society of Professional Journalists, Koretzky prowled Craigslist for manual typewriters, 35mm cameras, Xacto knives, rubber cement, pica poles and those dreaded proportion wheels.

The students spent three weekends patching their paper together. They converted a seldom-used men’s restroom in the Student Union into a darkroom. They typed out their stories, edited the hardcopy and retyped, and pasted photos and text columns onto boards. The only cheat was an iMac used to format the text into paste-able columns, like a typesetting machine.

why bother?

Koretzky described the experience on his blog much better than we can here. He also mentioned it on a national listserv for college journalism advisers. Some winced. Why drag students through a process that is now obsolete? Why spend time and money on yesterday’s media, particularly when we struggle enough to prepare students for today’s? One adviser called it a “dumb idea.” Another said it was indulging a newspaperman’s nostalgia. And it wasn’t just them. An online commenter called it “another reinvention of the wheel.”

However, for Koretzky and his students, the upside was definite and quantifiable.

The loss of technology compelled students to be more collaborative and engaged. When 35mm film gave them a 36-shot limit, they took more care with each frame. When they banged out stories on typewriters, they stopped and considered each sentence before committing it to paper. It was slower, more difficult and much more frustrating, but it taught them to exercise the human muscles behind journalism, and not to rely so much on the automated crutches.

This kind of experience doesn’t make a journalist, but it makes a talented journalist more

nimble and creative. If all the usual technological aids fell away unexpectedly, then it would give them the confidence to say, “I’ve been here before.”

New appreciation for tech

Another benefit is that students are spending more time in the newsroom since their All on Paper experience, and the quality of their work is better — Koretzy estimates a 10 to 15 percent improvement — because they take more time with it. At the very least, they have a new appreciation for their computers and software.

And where some see no point, Koretzky sees the main point: job marketability. “Every interview, this question usually comes up — ‘Tell me a war story. Something that separates you from the all the people who have the same resume that you have.’”

Despite the success, other schools don’t seem eager to try it themselves. Only Flagler College, the University of Florida and the University of Texas at El Paso have signed up so far. It’s understandable, given that it’s hard enough to put out a consistent, quality student publication with technology, let alone without it.

“I certainly don’t see it as a challenge to technology, and I think that’s where some

people mistook this,” said Brian Thompson, faculty adviser for the Flagler College Gargoyle (which is, ironically, an online-only publication). “Some people said ‘Does this send the wrong message? Shouldn’t we be stressing technology as opposed to stressing the past?’ I don’t see that argument. It’s about stressing the core roots of journalism.”

Thompson is right. He’s seizing an opportunity that the rest of us are missing. Koretzky’s equipment should be shipped from school to school, with a few hundred dollars raised here and there for food, film and other supplies.

Students should be reminded that what they’re producing is an artifact. Even as papers move to online-only editions, as Flagler’s Gargoyle did a year ago, this emphasis on a finished product is invaluable. In some regards, the paradox of composing electronically and for the web is that the story, page, or newspaper never feels like it’s done. It feels infinitely revisable, making students’ successes, and their mistakes, seem ephemeral.

An exercise in futility flexibility

We don’t champion this project because we think that student editors will, in fact, one day be faced with a disaster that necessitates their putting together a paper the old-fashioned way. We defend it because we can’t imagine they would be as capable of facing the everyday failures that do arise unless they learn the sort of teamwork, thoughtfulness and engagement that the old-fashioned way both requires and fosters. This, we think, is what All on Paper is trying to instill.

Alexa Capeloto and Devin Harner are assistant professors of English at John Jay College of Criminal Justice/City University of New York, where they direct the journalism program.

In the early ’90s, Devin’s high school paper was transitioning out of hot wax and Xacto knives and into pagination. By his senior year, they had begun to use PageMaker, but the system was still buggy. When they were putting together the first issue in September it got late. Real late. And then PageMaker crashed. They ended up doing paste up, but not before the police and the fire trucks came roaring up to the school. One of the editor’s moms worried that no high school student in their right mind would actually be working on the newspaper that late, even with the new Red Hot Chili Peppers CD for inspiration, and feared the worst.

Just a few years later, Alexa was laying out her high school’s weekly student newspaper, The Warrior, on a 9-inch monochrome Macintosh screen. With only a regular printer at hand, she printed each page in quadrants on letter-sized paper, and a graphic arts teacher spliced and taped the four sheets together on a broadsheet for printing. If you look closely, you can still see the glaring evidence that each page of the Warrior is actually four in one. Now that’s value.

Education content is sponsored by the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism, which offers an intensive, cutting edge, three semester Master of Arts in Journalism; a unique one semester Advanced Certificate in Entrepreneurial Journalism; and the CUNY J-Camp series of Continuing Professional Development workshops focused on emerging trends and skill sets in the industry.

> How to Have a Paper Ball at JournoTerrorist

> How to Build a Newsroom Time Machine at JournoTerrorist