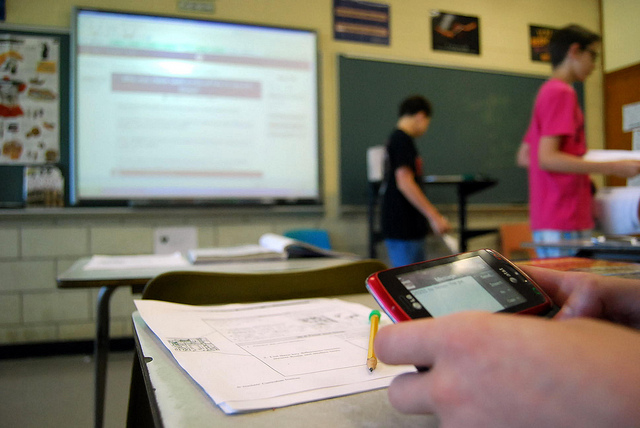

As we noted in August, cell phones are in the hands of the vast majority of adults, and whether schools like it or not, they’re in the hands of most students. While many schools still see cell phones as a distraction rather than as an

educational tool, it’s hard to deny that these devices are quickly becoming the primary means by which we communicate, in or out of schools.

For most teens, it’s not the “phone” part of a cell phone that they use most. Rather it’s text messaging. A Pew survey from last summer found that one in three teens sends more than 100 text messages a day — and more than 3,000 messages per month. Statistics like this point to all sorts of possibilities for educational opportunities around texting, particularly if you want to tap into the tools that teens are already using.

But text messaging has other benefits as well. Unlike apps that are only available on certain smartphones, or mobile websites that are only accessible on Internet-enabled devices, text messaging is widely available. This makes it an important and accessible communication tool, one that can meet the needs of schools and communities.

Group SMS for learning

Meeting that need is the goal of Celly, a startup out of Portland, Ore. A simple description of the new company: Celly offers SMS-based group messaging. Anyone can create or join a group by visiting the website or by sending a text to C-E-L-L-Y (2-3-5-5-9). And it’s free to use (not counting what phone companies

charge for messaging).

Classrooms can use the service to take quick polls and quizzes, filter messages, get news updates, take notes, and organize group study — all in real time.

Though it might seem like a simple premise, Celly’s messaging tool is actually quite multifaceted, and the founding team — Russell Okamoto and Greg Passmore — aims to make it work for schools and civic organizations.

In a school setting, considering the privacy and safety issues that arise around any social network, particularly one used by teachers and students, is a top priority. Messaging via Celly happens without sharing phone numbers, for example, and a number of controls allow group administrators to approve or kick people off. Groups — or as Celly calls them, “cells” — all have unique names and can be private or public, the latter being indexed by search engines. The cells can be configured to be open, allowing anyone to send messages; they can be moderated, so that the administrator must approve each message; or they can be alert-only, so that only the cell’s administrator can message group members.

Messages can be accessed via cell phones (obviously), but also via the web. Celly has a polling feature, so that cell phones can be used in lieu of devices like “clickers” to poll and quiz students in class. Celly also gives users the ability to @-message themselves for quick note-taking. And with no limits on the number of people that can join a cell, small groups can use it for study groups, classes can use it for

discussions, and entire schools can use it for messaging.

Tools for information organization

Cells can also be set up with “receptors,” allowing them to track any web feed and filter messages based on certain hashtags or locations. This means that the cells can be used to organize and aggregate content, and as cells can be connected — via these receptors — to other cells, it could be a way for grades, schools and districts to automate information flow. A classroom’s cell could get updates when a certain blog is updated, for example, or an administrator’s cell could get updates summarizing activity from all the various cells and groups.

In other words, Celly can be used to send messages home from school — reminders about homework assignments, for example — but it can also be used to monitor local and relevant news and information — all in real-time, all sent to users’ cell phones.

Celly is developing Android and iPhone apps, but it’s working to make sure that its tool is available to anyone, whether or not they can afford a smartphone. The startup also wants to meet the needs of its users first. Beta testers include a number of Portland-area high school teachers, as well as the city’s Gang Violence Task Force.

Audrey Watters is an education technology writer, rabble-rouser, and folklorist. She writes for MindShift, O’Reilly Radar, Hack Education, and ReadWriteWeb.

This post originally appeared on KQED’s MindShift,

This post originally appeared on KQED’s MindShift,

which explores the future of learning, covering cultural and tech trends and innovations in education. Follow MindShift on Twitter @mindshiftKQED and on Facebook.

> Cell Phones in Classrooms? No! Students Need to Pay Attention, by Greg Graham

> Why Schools Should Stop Banning Cell Phones, and Use Them for Learning, by Audrey Watters/MindShift

I Agree,