The stereotypical videogame player is a young male under age 18, but study after study has shown that the majority of the game-playing population does not fall into that demographic. Only 18 percent of gamers are under age 18, and women over 18 represent a significantly greater proportion of this population (37 percent) than do boys age 17 or younger (13 percent).

With the explosive growth in social gaming, particularly on Facebook, more games are being targeted at women. Games like Farmville and Pet Society, while not explicitly aimed at women, have been embraced by an older, female gaming population.

But what about girls? Videogames are increasingly considered an important tool for learning. And even though plenty of women do play videogames, there is still a sense — particularly among girls — that games are a “boy thing.”

Building Games for Women, Girls

That girl-gamer audience is the focus of the Vancouver, B.C.-based gaming studio Silicon Sisters. The first female-owned and run videogame studio in Canada, Silicon Sisters is committed to building games for women and girls by women and girls.

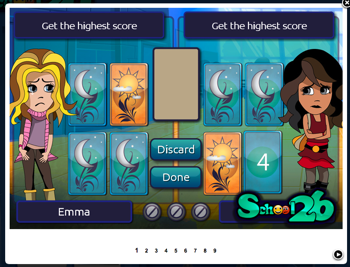

Founded by former Radical Entertainment executive producer Kristen Forbes and former Deep Fried Entertainment COO Brenda Bailey Gershkovitch, the studio released its very first game, School 26, to critical acclaim back in April. (We featured the game in an April round-up of the best new educational apps of the month.) The studio plans to release its next School 26 game — Summer of Secrets — next month.

The School 26 games are geared toward tweens and teens, and the storyline is built around the very complicated social hierarchy of high school. You play the game as a young girl who’s a newcomer to a school. She comes from a nomadic family, which has made it difficult for her to maintain long-term friendships. As she enrolls in this, her 26th school, she strikes a bargain with her parents: If she can make friends, they’ll stay put.

So the player of School 26 must help the character do just that: build friendships and navigate the sticky, awkward and sometimes awful moral dilemmas of school. These range from power struggles to peer pressure, romance, betrayal, alienation, acceptance — all real and relevant situations that girls face every day.

The player must select appropriate emotional responses to certain scenarios and answer quizzes that provide insights into players’ personalities. The emphasis here is on empathy and networking.

All talk, no action

That’s a very different set of goals and behaviors than what most videogames encourage. There isn’t swordplay here. No princesses to rescue. No alien invaders to vanquish. There isn’t “action.” There’s “talk.” The rewards aren’t cash or weaponry. The skills honed in School 26 aren’t the ability to time your jumps or dodge bullets or land killing blows. Of course, there are plenty of casual games aimed at tweens that aren’t action-oriented, and there are lots aimed at girls. But unlike many games that target this girl market, there is no emphasis on shopping, fashion or beauty in School 26.

The Silicon Sisters say all their games will emphasize this sort of “social engineering” — an emphasis on relationships and communication. These are important skills for girls and women to develop, the studio argues, and will allow them to navigate the sometimes treacherous social situations.

As the female gaming population grows, it’s likely that more companies will begin to cater to this market. But as it stands, there still aren’t a lot of games that meet women and girl gamers’ needs. A recent report by the entertainment market research firm Interpret, titled “Games and Girls: Video Gaming’s Ignored Audience,” argues that the female gaming market is far more nuanced than some of the “casual-centric reputation” suggests. Indeed, 44 percent of those who responded to the survey say that they prefer genres other than exercise, music, and casual games — the kind that are most often marketed to women and girls.

But making games for girls isn’t simply about providing good entertainment. Some of girls’ reluctance to play videogames may have other repercussions: a lack of familiarity with or comfort around technology, for example, and a missed opportunity to learn more about science, technology and engineering.

Audrey Watters is an education technology writer, rabble-rouser, and folklorist. She writes for MindShift, O’Reilly Radar, Hack Education, and ReadWriteWeb.

This post originally appeared on KQED’s MindShift, which explores the future of learning, covering cultural and tech trends and innovations in education. Follow MindShift on Twitter @mindshiftKQED and on Facebook.