I’ll forgive you if you don’t yet know it, but I’m America’s Next Great Pundit — or at least that’s what Washington Post readers decided last week. After reading everything from blogs to live Q&A chats to video roundtables to traditional Op-Eds, voters on the Post’s website winnowed 1,400 contestants down to one: me.

I’m not letting it get to my head, mind you, but I have been thinking a lot about what it means to get this kind of break by democratic instead of meritocratic means. It seems to me that this is an important — even fundamental — divide in the media world. When pundits become elected figures, they risk diminishing their prestige and expertise. And social media played a crucial role in helping me build a voting audience for my work.

How It Worked

The contest was fairly straightforward. First, the Post cut the 1,400 entries down to 50, and selected five “judge’s picks” from these to automatically advance. The top five vote-getters joined them in the “Blogging Round.”

After we spent a week posting twice a day to the Post’s website, the judges declared Nancy Goldstein, who would eventually advanced to the final, as that round’s winner. The rest of us faced the voters again, and the top three joined Nancy in the next round.

Next, we remaining four had a live online chat with readers and a taped debate with Post editorial writer Jonathan Capehart. From then on, there were no more judges’ picks, and the Post reversed the voting format to “Vote a Pundit off.”

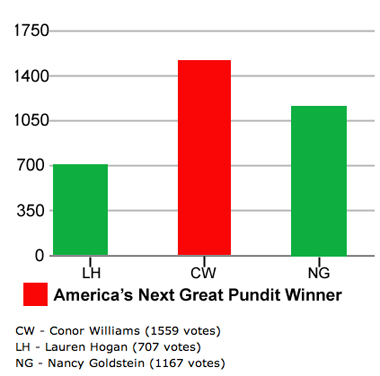

Finally, the surviving three contestants wrote op-eds in the November 1 edition of the paper before facing one final round of voting. With 1,559 votes to Nancy’s 1,167 and 707 for the other finalist, Lauren Hogan, I won the crown: A weekly column with the Post and all its attendant glories.

Get Out the Vote

Naturally, I told everyone I knew about the contest. I emailed everyone in my address book, reactivated my Facebook account, joined Twitter (@conorpwilliams), and generally became an online pest of serious proportions. Social media was part of my success in the contest, but it also did serious damage to my self-respect: How many status updates pleading for votes in an online contest can you make before Facebook starts wondering if you’re a spambot? (Not as many as you’d think.)

Within a week, I’d done interviews with any media outlet that would have me: The Bowdoin Orient (the paper at my alma mater), the Georgetown Hoya, Georgetown Voice (graduate school), and the Kalamazoo Gazette (my hometown paper). Soon I had a movement and a unified message. Countless friends at Georgetown and Teach For America, the education reform organization that got me my first job out of college, helped me mobilize support when rules changed or momentum shifted.

One particularly enthusiastic grad school colleague, Paul Musgrave, led my social media effort. He joined Twitter, pushed the #Conor4Pundit hashtag and set up a now-dormant “Conor Williams for Pundit” fan page on Facebook.

If this sounds more like an election than a writing competition, that’s the point. While my work in the contest garnered some praise, at the end of the day I needed an active voting coalition to survive.

The Brave New Online World

So that’s how I became a pundit. I suggested at the outset that this sort of contest isn’t without its costs. So what’s wrong with making these decisions democratically? Well, nothing, if you’re electing someone for a position where likeability is a crucial part of doing the job well (a senator, or a president, say). If you’re trying to make a decision on the basis of merit, however, majority voting is notoriously unreliable.

Imagine if we made our environmental policy decisions by means of majority votes! Even if there were an overwhelming scientific consensus that one set of policies was the best path for the community, this would be no guarantee that most voters would support them. In some cases, we want experts to make these sorts of decisions, instead of democratic majorities. Do we want the public to have the final vote deciding the specifics of our national response to climate change?

Does a process that motivates contestants to build a voting coalition also reward the best writers? I’m not sure. Fortunately, likability and public image are important components of “great” punditry (oxymoronic as that term may be). Pundits occupy a middle ground between intellectuals and entertainers. They are experts, but not necessarily policy wonks.

As I see it, the more interesting question concerns the online mobilization I just described. There’s a difference between a talking head who courts public favor, and a talking head who actively builds his or her audience. This is where we might want experts to take a role in the contest. If we’re trying to find a truly talented writer, we might want to avoid choosing him or her on the basis of majority rule.

The Dismal Democratic Future?

This contest isn’t the first instance of media democratization. In fact, it’s not even close. Preeminent media institutions demanding and producing high quality journalism have been losing ground for years. The nation’s greatest magazines and, especially, newspapers are struggling. Meanwhile, other news outlets — especially blogs and cable news networks — have never been stronger.

In other words, media outlets that target and pander to constituencies are thriving. Sure, even the country’s most serious news institutions have always had an eye on cultivating a particular readership, but this is still a far cry from Fox News’ style of relentless messaging. At the same time, some bloggers have produced remarkable political analysis of unprecedented quality (see Nate Silver and FiveThirtyEight, for example), but they stand out because of their rarity, in my opinion.

Obviously the growth of online media is helping to blur the line between these two sorts of news sources. The New York Times hired Nate Silver, after all. Informed opinion writing by bloggers like Silver and the Post’s Ezra Klein serves to enrich and broaden our public discourse.

Except, to paraphrase Dr. Seuss, when it doesn’t. Because not all bloggers are as careful with the numbers and the facts. Free, rapid information is great when it’s accurate, but it can be devastating to public discourse when it’s not. The democratization of news coverage and commentary threatens the place of expertise in reporting. In other words, when everyone gets a megaphone, there’s no reason to expect the debate to improve. When expertise loses its weight in journalism, difficult truths get lost.

Instead of considering political realities, we trade in convenient fictions, and myths come to compete with the truth on equal footing. Want to know why climate skepticism is on the rise, even when scientists are nearly unanimous on its causes and consequences? Prominent news outlets are pretending that there’s really a debate.

What the Post Gets

So what should we make of the Post’s contest? It’s probably true that traditional journalistic institutions will need to continue finding ways to build their online presence and “democratize” their approach to news. This contest gave the Post a good deal of interesting content from (mostly) new voices in the media world.

On the other hand, we should remember that news analysis isn’t the same as vote chasing. Expertise may be losing prestige in the new online media world, but pandering rhetoric is no substitute.

Our political problems are very real, and our pundits should be ready to approach them as such — even when they’re elected. I’m going to do my best. If the American public debate continues deteriorating, blame me. Or better yet, blame my background and my social networking.

Conor Williams recently won the Washington Post’s “America’s Next Great Pundit” Contest. He is a PhD candidate in Government at Georgetown University, an alumnus of Bowdoin College and Pace University, and a former Teach For America Corps Member. In addition to his weekly column with the Post, Williams has co-authored several essays on American progressivism with John Halpin at the Center for American Progress. He has also been published on DissentMagazine.org and FrontPorchRepublic.com. Follow him at @ConorPWilliams on Twitter.