Who owns your copy of “War and Peace”? If we’re talking about a dog-eared paperback copy of “War and Peace” that you purchased in your college bookstore, then you own the copy for purposes of copyright law. But if we are talking about an e-book version of the latest translation that was bought online and downloaded to an e-reader or other mobile device, then the question of ownership of the copy is not so simply answered. Unlike works published in print, electronic works are typically sold subject to agreements, in transactions that look less like an outright sale and more like a limited license.

Owner Versus Licensee

Ownership of a copy is an important concept in copyright law. Ownership of a copy of a work is distinct from ownership of the copyright in a work, which is retained by the author or publisher of a book or other work. Ownership of a copy determines whether the copyright owner has the right under copyright law to control subsequent transfers of the copy by sale, gift, rental or lending. In the case of computer programs, ownership of a copy determines whether the program may be used for specified purposes without infringing the copyright owner’s rights.

In the last several decades, questions concerning the ownership of copies of digital content have arisen with respect to various kinds of digital content. The federal courts are currently grappling with the issue in the context of audio CDs, videogames and software in a trio of cases that were recently argued before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. The resolution of these disputes may help predict how other federal courts will view the issue of ownership of copies of e-books and other electronic publications, such as the proliferating category of all digital magazines targeted at Apple’s iPad and other tablet devices.

The Copyright First Sale Doctrine

The copyright first sale doctrine has its origins in a dispute that arose when the publisher of a copyrighted novel sought to preclude dealers who purchased copies of the book for resale from reselling it at a price lower than that stipulated by the publisher. The publisher relied on language that was printed on the inside cover of the book that established a specific retail price and stated that dealers were not licensed to sell it at a lower price, and that a sale at a lower price would be treated as an infringement of the publisher’s copyright. In Bobbs-Merrill Co. v. Straus, the U.S. Supreme Court concluded that this notice did not give the publisher the right, under copyright law, to limit subsequent sales of the books by the initial purchaser.

The ruling in Bobbs-Merrill Co. v. Straus was subsequently codified in what is now Section 109(a) of the Copyright Act, which states that “the owner of a particular copy or phono record lawfully made under this title, or any person authorized by such owner, is entitled, without the authority of the copyright owner, to sell or otherwise dispose of the possession of that copy or phono record.”

As evidenced by a nation that is thick with used bookstores and charity used book sales, under this section the purchaser of a printed book can sell, give away or even burn the copy without the permission of the copyright owner.

Section 109 does not, however, define the critical term “owner … of a copy,” leaving copyright officials and federal courts to interpret it on a case-by-case basis.

Owner of a Copy

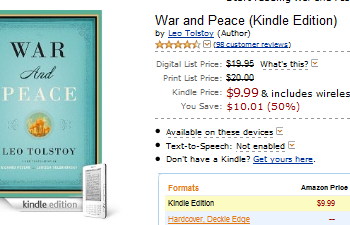

It’s easy to conclude that the purchaser of a printed book who pays the price and walks out of the store with it is the “owner” of that copy of the book, because the transaction has two significant incidents of a typical sale: Payment of a single price, and transfer of permanent possession of the item. But as an episode involving the remote deletion of e-books from Amazon’s Kindle e-reader device demonstrates, some e-book ecosystems allow the seller to remotely delete content, a fact which makes the transfer of possession potentially less than permanent. E-books are also typically sold subject to an agreement containing a variety of provisions limiting purchasers’ rights. For example, the Terms of Use available on the Barnes and Noble website contains provisions that restrict the right to transfer “digital content” to another device and limit the right to lend digital content to another user.

The Register of Copyrights recently studied the issue of ownership of digital content on mobile devices during the triennial rule-making proceeding under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. The issue arose in the context of the Register’s determination of whether the purchaser of a device such as an Apple iPhone is the owner of copies of the firmware installed on the device, and thus whether the purchaser has the right to modify the software in order to “jailbreak” it. The Register threw up her hands and rested her decision instead on the “fair use” doctrine, commenting that even the federal courts have disagreed as to the proper test under copyright law for determining ownership of software copies.

Current Disputes

The struggle in the federal courts over the issue of ownership can be seen in three cases argued simultaneously in June in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Each case presents the issue of ownership of copies under copyright law in a different context, although all three involve reliance on contractual language to limit the rights of purchasers and recipients of copyrighted content. In an unusual move, the court agreed to the request of the parties to these cases that they be heard simultaneously by the same appellate panel, due to the similarity of the issues they present.

Universal Music Group v. Augusto involved online auctions of promotional CDs distributed by the music company to reviewers, radio stations and others in or associated with the music industry. The CDs were distributed by the company with an included agreement stating that the CD was licensed to the recipient and that resale or transfer of possession was not permitted. Universal argued that the language in the agreement precluded a finding that the recipient was an owner under copyright law. The trial court concluded that, among other things, the transfer of possession of the CDs to the recipients for an indefinite period of time indicated that the recipients were owners of the copies.

Another case, Vernor v. Autodesk, involved packaged software that was resold by the original purchaser to a reseller who posted it for sale in an online auction. Autodesk, the software developer, relied on language in the shrink-wrap license agreement accompanying the software in the original transaction, stating that the distributor granted to the purchaser a “non-exclusive, non-transferable license” and prohibited subsequent transfers of the software without its consent.

Autodesk argued that this language prohibits its original purchaser from disposing of Autodesk software in the secondary market. The trial court disagreed, concluding that because the original transaction allowed the purchaser to retain possession of the copy for a single, up-front payment, the transaction was a sale that transferred ownership of the copy. Significantly, however, the trial court found that rulings in the Ninth Circuit (the federal appellate court which the trial court was bound to follow) were in conflict on the issue and that if the court followed the most recent of those conflicting opinions, it would have ruled in favor of Autodesk on the issue of ownership.

The third case, MDY Industries, LLC v. Blizzard Entertainment, Inc., involved videogame software, and the question of whether the terms of the end user license agreement accompanying the videogame preclude a finding that the purchaser is the owner of a copy under 17 U.S.C. § 117(a). That section affords owners certain rights to use copies of computer programs. In MDY, the issue was not the transfer of the videogame software, but the use of the videogame with a third-party computer program that is not approved by the video game developer. The trial court concluded that purchasers’ use of the videogame software with unapproved programs was not protected under Section 117(a) because the end user license agreement had so limited the purchasers’ rights that the transaction could not be considered the sale of a copy. Like the court in Vernor v. Autodesk, the court in MDY referenced the conflicting rulings in the Ninth Circuit on the issue of ownership, but chose instead to follow the later rulings that are more favorable to the position of content owners.

Conclusion

What is at stake in these cases is not the ability of copyright owners to limit transfers or certain uses of their copyrighted works at all, but whether they may do so under the Copyright Act. The Copyright Act affords content owners powerful and versatile remedies that are not available if the limitations that content owners place on their works are viewed merely as contract provisions, and the violations of them are treated as breaches of contract.

What is at stake for purchasers of e-books and other electronic publications is whether they will be treated under copyright law as owners of copies of the books and magazines they download, or simply licensees with limited rights.

Jeffrey D. Neuburger is a partner in the New York office of Proskauer Rose LLP, and co-chair of the Technology, Media and Communications Practice Group. His practice focuses on technology and media-related business transactions and counseling of clients in the utilization of new media. He is an adjunct professor at Fordham University School of Law teaching E-Commerce Law and the co-author of two books, “Doing Business on the Internet” and “Emerging Technologies and the Law.” He also co-writes the New Media & Technology Law Blog.

I’m afraid I will not own an electronic reader anytime in the near future. Why would I pay for something I can’t own? Especially a book or music. Those are things you can enjoy over and over. That is until the corporate giants delete it from your e-device. Thanks PBS for bringing to light issues that are important. You are our last beacon of hope for true journalism. I will stick to good ole fashioned paper backs. Besides, I love the smell of an old book. Can’t get that from your e-reader.

Many of our nation’s justices have publicly admitted that they don’t even know how to write/send an email. They’re going to go with consumer perception of ownership of digital content as the standard.

Consumers are given the perception that they own the digital copies of books purchased, and I strongly believe SCOTUS justices would uphold this perception as reality should a case come before them.

This is why I love O’Reilly Media (not at all related to Bill O’Reilly). When they sell you a electronic book, it’s DRM free, unlimited downloads and you are able to search and print it. They have a variety of format including PDF, Android,… Kindle and Epub (for Iphone and Sony readers) formats. Cut and Paste, searchable and printable. They can’t take it away.

http://oreilly.com/store/index.html

(I don’t work for them)

I bought it, I paid for it, it’s mine, I’m going to keep it. Or do whatever else I want to with it. The loophole in most clauses that cause DRM types to go bananas boils downto you can make a copy for personal use. You figure out the rest, and as always, do the math.

The question of ownership of digital copies *should* actually be pretty easy to determine. The Copyright Act has this to say about what a “copy” is:

“Copies” are material objects, other than phonorecords, in which a work is fixed by any method now known or later developed …

Due to the very definition of “copy”, then, whomever owns the device on which the digital copy is stored is clearly the “owner of the copy”. I think content owners are going to have a hard time selling the idea that *they* own the customer’s Kindle, iPhone, computer, or other e-book reading device.