Back in 2008, I co-organized a conference called Beyond Broadcast. That year’s theme was “mapping public media,” and was designed to both call out the rising importance of maps as a platform for sharing digital media, and to “map” the fragmented universe of public service media projects.

The maps I found at the time underscored the siloed nature of news production. There were maps of public TV stations, community media projects, and citizen bloggers, all maintained separately by different entities and aimed at very different users. Such isolation made it difficult to trace the relationships between these different kinds of outlets in any one place.

However, as concerns about local media ecologies have sharpened — spurred in part by the focus of the Knight Commission on the information needs of communities — such mapping has taken on a new urgency. Knight provides interested locales with a starting point: A simple survey for assessing the health of their information environment. The Knight Media Policy Initiative at the New America Foundation (NAF), where I’m now a fellow, has begun to develop a set of analyses of local media/governance ecologies.

The goal is to “align policy recommendations with needs on the ground,” said Tom Glaisyer, who is coordinating NAF’s initiative, and plans to work with others seeking similar information. Various scans of the community media landscape have already been launched, including a survey by the Free Press, a field scan by NAMAC, and this crowdsourced directory of cable access stations. One-off accounts of local news ecologies have also become more common, like Pew Research Center’s January study of Baltimore’s “news ecosystem” — the disarray of which was famously chronicled in the HBO series “The Wire.” Pew’s study suggests that, amidst a rapidly expanding universe of local news projects, newspapers are still leading the pack in providing original reporting, but also notes:

The array of local outlets within this snapshot is already substantial, and as times goes on, new media, specialized outlets and local bloggers are almost certain to grow in number and expand their capacity, particularly if the Sun and other legacy media continue to shrink. New outlets such as local news aggregators, who combine this increasingly mixed universe into one online destination, have cropped up in some other cities such as San Diego. There is a good deal of innovation going on around the country, much of it exciting and promising. But as of 2009, this is what the news looks like in one American city.

A Bird’s-Eye View

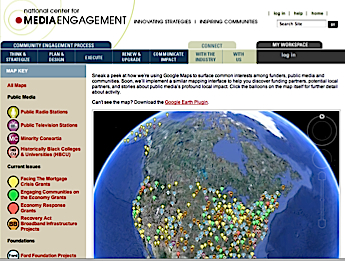

In order to get a better sense of community news across the country, The National Center for Media Engagement (NCME) embarked on an ambitious project to combine several media maps into one using Google Earth.

Funded by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the NCME generally works with public radio and TV stations to help them develop outreach strategies for local communities. This map emphasizes those stations, but also includes a variety of other “layers” that represent possible community allies for media makers, such as historically black colleges and universities. Also noted are rising efforts to wire communities for broadband access, and news projects underwritten by funders, including Knight, the Ford Foundation, MacArthur, and CPB.

Layer by layer, the map provides a fascinating look at the geographic distribution of different funding priorities, such as grants that provide media resources to communities facing waves of foreclosures. When all of the layers are clicked on, the map offers a snapshot of how particular locations — such as San Francisco, pictured at left — are thick with overlapping projects and outlets, while other parts of the country go begging for resources. Lone stations — take KILI Radio in Porcupine Butte, South Dakota, for example — dot the map among blank expanses of terrain, while a cluster of dots in a big, blue stretch remind us that Hawaii has its own public media presence.

This map is just a start: NCME promises its members that, “soon, we’ll implement a similar mapping interface to help you discover funding partners, potential local partners, and stories about public media’s profound local impact.” But there are other layers to be added, too, that would tell a more complete story about all of the various outlets and independent projects providing vital news and information across the country.

Mapping From the Bottom Up

For Sandra Ball-Rokeach, a professor at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School of Communication, a crucial missing layer is ethnic media. Ball-Rokeach heads up the Metamorphosis Project, which studies how the communications habits of urban communities are shifting as they become more diverse and globalized.

The project boasts its own map of neighborhoods throughout Los Angeles where researchers have been deployed to interview residents, organizations, and business and community leaders. Their goal is to develop a deep understanding of what they call “indigenous storytelling networks.”

Their research reveals that stories about diverse communities are often reported by local ethnic media outlets, which might be speaking only to one portion of the community. These stories are then passed along through both personal networks and through community organizations, like local non-profits.

In this model, the health of the storytelling network is contingent upon other aspects of the community, what Metamorphosis researchers call “the communication action context.” These factors include the availability of public spaces, neighborhood safety, and transportation resources, as well as more familiar infrastructure provisions like broadband access. If community residents are discouraged from talking to one another because their context is lacking, then simply establishing new news projects won’t fix the problem.

“People put together these ecologies,” said Ball-Rokeach. “They’re not put together for them.”

While NCME’s map uses technology to aggregate information about existing and proposed media projects, Ball-Rokeach and her team use a variety of face-to-face investigation methods, including long-form interviews and focus groups, to determine how people are actually sharing and using news to “accomplish everyday goals.”

She describes a current USC local media project, called “Alhambra Source,” which builds upon Metamorphosis research in the city of Alhambra, bordering Los Angeles to the east. With a population of less than 100,000, Alhambra has large numbers of Latino and Chinese residents. Ball-Rokeach said much of the local reporting is conducted by outlets who communicate with their users in Mandarin. The “Alhambra Source” site will translate news summaries into Spanish, English and Mandarin, allowing stories to be shared more easily across different parts of the community, as well as providing opportunities for residents to share their own stories.

“It’s kind of exciting,” she said. “We understand that the likelihood of success is low, but we think it’s worthwhile because creating sites for homogenous populations is probably not where the action is, given that even medium-sized communities are becoming more diverse.”

Bridging the Gap

In order to make sophisticated funding and policy decisions, national efforts like the FCC’s current Future of Media Project will need to find ways to bridge these disparate approaches. Right now, communications researchers are still asking very different questions, and attending to different priorities.

Developing common questions and data collection standards will require time, effort and focused collaboration. The challenge is not small, especially given the rapid changes in communications technology, and the pace of experimentation.

“It’s a very dynamic process,” said Ball-Rokeach. “People resist our efforts to make them static.”

Jessica Clark is director of the Center for Social Media’s Future of Public Media project, a Knight Media Policy Fellow at the New America Foundation, and the co-author of Beyond the Echo Chamber: Reshaping Politics Through Networked Progressive Media.