Sergii Danylenko and Anna Prymakova asked me to speak about “changes in media over the past five years“ at MediaCamp Kyiv last week. It’s a pretty standard topic of discussion for me, but I felt that it would be more interesting and more useful to look at changes in media over the past 550 years. What follows is a hyperlinked version of my talk.

I recently received an email from NowPublic, a popular citizen journalism website in North America, with the subject “Now Hiring.” This is a rare thing in the field of journalism these days – citizen or traditional – and so I wanted to see what they are paying for and how they are covering the expenses. It turns out that NowPublic is not paying you to be a journalist – that is, not to publish content, but rather to read it. And, more importantly, to get others to read it. They will pay you for “views, visitors, and ad clicks.” And they will pay you to refer others to view content and click on ads. In economic terms we would say they are paying to create a false demand for an overabundant supply.

For me, this exemplifies the state of news media: there is now, for the first time in the history of the world, an abundance of content and a scarcity of attention. But how did we get here? To better understand that we need to go back to 1435 in Northern France when Jean Miélot, a French priest and scholar, first began working as a scribe for Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy.

Since the invention of the papyrus scroll in Egypt over 4,000 years ago, this is how books were always produced: by hand, and one by one. Scribes almost always worked either for the church or for the aristocracy, and so princes and priests decided which books were to be copied, and which were to be banned. In 1435 Jean Miélot was given what was at the time thought to be a very prestigious job, just as prestige was associated with journalism as little as five years ago.

But then something happened. Just one year after Jean Miélot was given his job as a scribe for the Duke of Burgundy, a German goldsmith named Johannes Gutenberg began working on a new invention. Taking inspiration from mechanical presses that helped produce olive oil and wine, Gutenberg invented movable type, which allowed for the mass production of books. In retrospect, it is hard to overstate the importance of this invention in Europe and, eventually, throughout the world. Previously it took months just to produce a single copy of a book. Now in a week you could create thousands.

Slowly, ever so slowly, books began to spread across Europe. In the 1440’s, 50’s, and 60’s the book was the new media of the day. And just like it has taken the world a long time to understand the power of the internet, it took Europe many decades to understand the social impact of the printed book.

There is a great irony that Johannes Gutenberg is best known for printing the Gutenberg Bible in the 1450’s. Previously, every bible was hand copied by scribes, and only priests and princes had access to what was considered the great book of wisdom. Other Europeans depended on priests to transmit the contents of the bible during their weekly sermons. I say that there is irony in the Gutenberg Bible because the Gutenberg printing press was eventually responsible for taking power away from the Vatican and the Catholic Church.

70 years after the Gutenberg Bible was published it finally became common for European authors to publish their own books using the printing press. Martin Luther was one author to do that. In 1522 he published a translation of the Bible in German rather than standard Latin. This was a direct challenge to the power of the Catholic church. Instead of relying on the few trained priests and scholars who spoke Latin, the Bible was now accessible to all literate Germans.

He then published his 95 Theses which quickly spread all over Europe, led to the Protestant Reformation, and the fall of the Vatican as the center of power in Europe. Without the printing press the Reformation could not have never happened.

Nor would have the Scientific Revolution of the 17th century or the Enlightenment of the 18th century. Both movements depended on the rapid and broad dissemination of ideas such as Copernicus’ On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, Vesalius’ On the fabric of the human body in seven books and Descartes’ Discourse on the Method. Perhaps the scientific revolution was actually ready to spread much earlier, but there was no way for the thinkers to publish, share, and build on the ideas of others.

And, of course, there would be no journalism were it not for the printing press. This is a copy of the London Gazette, which was the first regularly published newspaper, and began as the Oxford Gazette in 1665.

The point that I am trying to make is that some technological innovations are so revolutionary that they change everything. The Gutenberg Press led to the Protestant Reformation, the Scientific Revolution, journalism, the Enlightenment, and, arguably, representative democracy. It created what is today a European continent with near universal literacy.

Before movable type, Europeans depended on priests to know what was inside of a book. Now they simply open its cover. That is a revolutionary difference. But what is important to remember is that not everyone benefited from the printing press. Scribes all across Europe protested. There aren’t good records of their protests, but I can just imagine their reasoning: that people would be overwhelmed by too much information; that they would become isolated reading at home rather than coming to church; that mediocrity would prevail if publishing was put into the hands of ordinary people. Basically, all of the same criticisms we hear of the Internet today. In the end, the scribes lost and the printing press won. With the benefit of historical perspective, we view the result as inevitable. And we are seeing the same dynamic play out today with traditional journalism and the participatory internet.

In the US a major newspaper closes down just about every week. Those that haven’t closed down yet are all losing money. There is no single major newspaper in the US right now that isn’t losing money. The question isn’t if the old model of journalism will die out, but when.

Which brings me to the next topic: that the World Wide Web is proving itself to be just as disruptive of a technology today as the Gutenberg Press was in the 15th century. The internet is growing up. There are now more Chinese internet users online than Americans.

Pew Internet found that one out of every five internet users in the United States uses a service like Facebook or Twitter to regularly update their status. For Ukrainians it might be LiveJournal and Kontact.

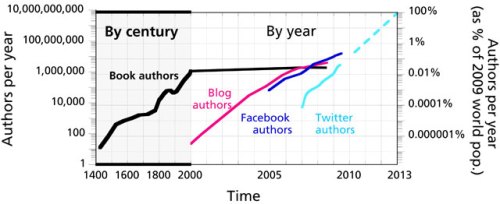

Two American researchers, Denis G. Pelli and Charles Bigelow, argue that we are charting a path toward “nearly universal authorship.” In their study they charted the rise of book authors per year from 1400 to today and compared that data with the number of blog authors, Facebook authors, and Twitter authors over the past ten years. As you can see in the above chart, it took 600 years to reach one million book authors per year. In contrast, it only took five years to reach a million blog authors, three years to reach a million Facebook authors, and two years to reach a million Twitter authors. What will be next?

There are some technological innovations are so revolutionary that they change everything.

What is the role of media if everyone is part of the production process? I believe that we will continue to see a rise in what Jessica Clark of the Center for Social Media calls “people centric media,” which spreads information, communication, and social capital across networks based on location, issues, and events. But how will media organizations and projects survive in an era where content is so abundant that no one is willing to pay for it? I want to stress that no matter how many conferences are held and white papers are published, there will never be a silver bullet to save the media industry. It is as useless of a task as convening scribes in the 15th century to discuss how they can save their industry. However, several new models and strategies are emerging which offer a glimpse into the future of people centric media.

Make the readers the journalists. In August 2008 the New York Times published a beautiful visualization of the final subway stops for every subway line in New York City. To do this they sent out reporters to take pictures, collect audio, and file their reports. A year later, a similar project called Mapping Main Street accepts contributions from anyone. It still requires an editor and designer, but in Mapping Main Street there is no distinction between reader and reporter.

Remove unnecessary reporters. Newspapers used to hire reporters to go to the police department, ask for the crime report, and then copy and publish it in the newspaper. Today that information can be published immediately and directly. Everyblock scrapes information from government websites and makes it available for ordinary citizens via web browser and mobile phone. Just as Europeans used to have to rely on priests to understand what was in a book, citizens used to rely on newspapers to understand about their community. Now they can see and engage with the information for themselves.

Remove unnecessary editors. Newspapers have a limited amount of space. Editors had to decide what was included in that space and what wasn’t. They were the ultimate gatekeepers of the day’s news. Today we are not limited by space, but rather time and attention. NewsTrust is a collaborative editorial site open to anyone which seeks to collectively rank the most relevant and trustworthy news.

Some reporting will always be expensive. For example, a 13,000 word New York Times article on events at Memorial Medical Center following Hurricane Katrina took two years and $400,000 to produce. With a $35.6 million loss last quarter, the New York Times can’t invest $400k in a single story. Fortunately for the Times, a non-profit organization called ProPublica footed most of the bill. ProPublica is funded by billionaire Herb Sandler who founded the Sandler Foundation in October 2006 after he got out of the finance and mortgage industry. (Good timing!)

Get your local community to fund local reporting. You can either get a few very wealthy individuals/organizations to fund your work, or you can get many people to donate a small amount of money to pay a journalist to report a story. This is the model of San Fransisco-based Spot.us, which describes itself as “community funded reporting.” Any journalist can make a pitch on the site about a story that he or she would like to report on. For example, in early July Lindsey Hoshaw was given an opportunity to board a ship to visit the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and report on it for the New York Times. But apparently, neither she nor the New York Times had the $10,000 to pay for the travel expenses. And so Hoshaw recorded a video of herself explaining why the reporting was important, why people should pitch in to help her cover the story.

Ellen Miller, the executive director of the Sunlight Foundation, pitched in $20. Tim O’Reilly, a well-known open source technologist and publisher, pitched in $100. Pierre Omidyar, the founder of eBay, pitched in $100. Craig Newmark, the founder of Craigslist, pitched in $50. Zoe Keating, a well known cellist offered another $20. Jennifer 8. Lee, a reporter for the metro section of the New York Times, donated $30. (Perhaps she felt bad that the New York Times was still able to pay her, but not Hoshaw.)

Four months after Hoshaw made her pitch on Spot.us her story was published in the New York Times with an accompanying slideshow.

Give some away for free, charge for the rest. This is the business model that is mentioned most often these days as a way to keep news organizations afloat. It is the strategy of GlobalPost, an international news site. You can go there now and read more articles for free than you likely have time for. But if you’re a real international news junkie, then you can pay an extra $200 a year for their “Passport” membership, which “offers an entrée into GlobalPost’s inner circle.” A couple weeks ago GlobalPost founder Phil Balboni claimed that so far they have 500 paying subscribers to Passport. He also claimed that GlobalPost is on pace to generate $1 million in revenue this yaer. (Their annual expenses are $5 million.)

At Global Voices the majority of our expenses are covered by private philanthropic foundations. The rest of our funding comes from four other sources: content commissions and underwriting, advertising, consulting, and online donations.

As you can see, it is becoming more and more difficult to find funding to support both media organizations and journalistic coverage. Then again, it might prove to be even more difficult to find anyone to pay attention to what you publish. It seems that the scarcity of attention is even more severe than the scarcity of funding.

Thanks for writing this David, it was a great read! I’d like to point you to Jurgen Habermas’ Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. It’s quite hard to read, but very insightful. In particular, one of the things he says is when the print media came out in full swing, it meant that only the literate now had access to the “public sphere” in terms of influencing politics and policies. Further, with a simultaneous cultural shift from communal to personal physical spaces, this narrower “public sphere” got increasingly privatized and myopic in its thinking. Habermas argues that this fundamentally changed the dynamics of democratic ways of governance.

One of the things that now changing with social media is that more and more people now have access to the public sphere, plus the sphere is more aware of the world. It’s this two-way bi-directional flow of thoughts and information that is very important. This is why bridging projects like Rising Voices and Video Volunteers and Gram Vaani are so much relevant in the context of the developing world.

thanks David, it’s good to put internet tools in perspective: Like when TV arrived, and people predicted the end of movies and cinema…

Good job ! One important element missing though. The ” invention” of the Table of contents which came almost 200 years after the printing press. What do you think ?

Thanks

PL

It sounds like journalists today also have to be marketers. They have to know who they are trying to reach and what will reach them. They have to pitch their stories to a broader audience so it has to be compelling. It sounds exciting. I think the key part will be keeping the momentum up.

Aaditeshwar,

Thanks for the comment. Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere is one of those books that I feel that I have read even though I haven’t because it’s been cited so many times. I’ve got an e-book version of it sitting on my iPhone. Now who is going to pay me to read it!? :)

Medea,

Indeed!

Patrice,

I think that Umberto Eco has given enough attention to TOC and related lists of late.

Michelle,

I wish that I shared your enthusiasm for self-pimping. But I agree with you, if you don’t want to pay someone to read what you write, then you’ll have to market it endlessly.

dear david,

thanks for including our authorship graph.

“there is now, for the first time in the history of the world, an abundance of content and a scarcity of attention.” nice! we present a more optimistic view of readership in our response to comments at the new york times blog.