If you’re following the twists and turns of Microsoft’s hostile bid for Yahoo, you can’t escape one name that keeps popping up in the media: Eric Jackson. As an activist shareholder in Yahoo, he has become the voice of the opposition, calling on Yahoo to accept Microsoft’s takeover bid — or any reasonable bid. Last year, he was instrumental in raising a ruckus online over Yahoo’s poor stock performance, and helped get Yahoo CEO Terry Semel ousted.

But what’s amazing about Jackson is that unlike the big-name activist shareholders such as Carl Icahn and Daniel Loeb who have huge war chests to buy up stock, Jackson is a small fish. He only owns 96 shares of Yahoo stock. Where Jackson has innovated is in using the tools of social media to gather support from other shareholders and get the attention of the media to make his case for corporate change.

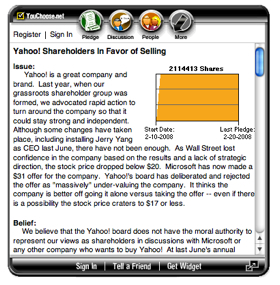

He started in the summer of 2006 with a blog called Breakout Performance to tout his corporate consulting business. After a blog post about Yahoo attracted more traffic than his theses about corporate governance, Jackson began his campaign to get Yahoo to change its strategy, a “Plan B for Yahoo” that was eventually loaded onto a wiki. He shot some videos and uploaded them to YouTube, and used a web widget called YouChoose.net to get people to pledge their Yahoo shares to his cause. Last June, Jackson went to Yahoo’s annual shareholder meeting to confront Semel in person.

After enough people voted “no confidence” in Semel and some board members at that meeting, Semel stepped down from the CEO post a week later. Jackson justifiably took credit for leading the charge against Yahoo management in the media and online. Later, he followed in the footsteps of financier Carl Icahn in calling for Motorola CEO Ed Zander to step down — albeit with much less money invested in Motorola than Icahn, with just 134 shares. But even though Zander did vacate the CEO post, Motorola’s stock continues to hover near its historic low point.

So how did Jackson, 35, with a PhD in business management from Columbia University, get so much attention with so little stock in those companies? In a wide-ranging Q&A, Jackson explained how the media was drawn to him as the consistent “other side” of Yahoo’s financial story — plus, he had the social media hook, too.

“When I launched the campaign [against Yahoo], I thought I could write about it on my blog,” he said. “But if I was a reporter [covering this], what would make this story interesting to me? Some guy writing a blog is not that interesting. A blog is great, but what if I also did a YouTube video and tried to use more social media? Then it wasn’t just a David and Goliath, individual-investor-rising-up story, but it’s also a novelty, new technology, social media story. I had never used YouTube before, so I went out and got a $30 webcam and hooked it up to my laptop and recorded myself speaking my blog post.”

But Jackson found out that social media was more than just a good story angle to get press coverage. Eventually, he got 100 Yahoo investors to pledge their shares to his Plan B cause through YouChoose.net. People helped give valuable feedback to his Motorola Plan B on a wiki, and a Facebook group helped spread the word about his actions.

Jackson has parlayed his success with Yahoo into a new activist investment firm he runs called Ironfire Capital, though it has less than $5 million in funding so far, he said. Jackson is convinced that other individual investors will take similar coordinated online actions against companies that are underperforming, bringing a democratization and decentralization of power to corporate governance similar to what’s happening to the media industry.

The following is an edited transcript of our phone conversation and email correspondence, touching on Jackson’s action last year against Yahoo and his current push for shareholders to accept Microsoft’s bid.

As an investor, what is your strategy? Do you hold the stock for a longer period of time or sell it after you turn it around?

Jackson: I typically hold stocks for one to two years. So there’s an expectation that I’m not someone who’s trading in and out, I’m a holder of the stock and I have the long-term interest of the company in mind. I’d like to see the value of that company increase over that time. If it does on its own accord, that’s great, and if I do get involved as an activist, I’d expect that the effects of that activism would be realized in the stock price over that one-to-two-year time period.

Activism doesn’t have to be public and critical. It can also be quiet and private. The philosophy is that if you speak up, and you can make some compelling arguments, then other shareholders will pay attention and agree with you. You can end up, as a very small shareholder, with less than 1 percent, having an argument that ends up being followed and believed in by quite a number of shareholders, thereby pressuring the board to make those changes.

How did you initially decide to take on Yahoo?

Jackson: I was watching Yahoo from afar as an individual shareholder in the fall of 2006 and was really disenchanted with the direction of the company. I said to myself, ‘Here’s a perfect target for an activist investment firm’ and it got me to thinking. Even though I didn’t have an $8 billion investment firm, I thought that the chances were good that there were other investors like me who were upset. And I thought I could use social media, I had started a blog just six months before that. I thought, with blogs in the political realm, there are examples of people coming together with a grassroots movement behind a political candidate, and suddenly this phenomenon brings a tremendous amount of attention to that particular candidate and adds to that momentum.

I thought, ‘Why couldn’t that happen in a shareholder context if you had a company like Yahoo that is well known and well followed and people have passionate opinions about it?’ No one would have cared if I went after a shipyard company. Yahoo is kind of like the Paris Hilton of the business media, it seems like magazines and newspapers love writing about Yahoo.

When you started the blog was it for Yahoo in particular or was it for other reasons?

Jackson: I started the blog for other reasons. I was a strategy and governance consultant, and I still do that today. I started the blog as a way to write about topics that I consult on [so] it could bring more visibility to me and my consulting firm. I started it in the summer of 2006 without getting much traffic at all. I noticed that certain topics would suddenly get more traffic than others. I had written a post about Yahoo kind of randomly, making the point about leadership in general, [writing about] Terry Semel, the CEO from 2001, after Yahoo had crashed from the dot-com bubble. He had been getting credit in 2004 and 2005 as being the steady hand, gray hair, Hollywood exec who showed the kids what leadership was and how a real organization should be run. And he was the reason Yahoo got out of its swoon.

But in my eyes, observing what he had done, it didn’t seem that Yahoo had succeeded because of his leadership, but more in spite of it. What happened at Yahoo, the recovery, would have happened no matter who was in his position because of the general resurgence in the Internet and the advertising market. That blog post generated a lot of hits and comments, and that was interesting to me. It’s a high profile company and a lot of people care about it, so if you started a campaign about it you could tap into passionate people.

So because you didn’t have a lot of money invested in Yahoo, was the motivation for your activism to make a point about leadership?

Jackson: Initially I bought 45 years of Yahoo, and then I bought 51 more shares, so today I own 96 shares of Yahoo. So that’s worth about $2,500, so clearly it’s not about the money. When I started it, I had no idea if I would be successful or not. The reason I did it was to see if I could get people engaged. Truly what I was hoping for was to get some people together and put a plan together for what Yahoo should do if we were running the company, and maybe we could meet with them and they would agree to implement one or two ideas. And if that happened we could claim victory and show we made a difference. And it would be the first of its kind, where individual investors took this idea of activism and got a company to change.

I started a Facebook group, and later on, someone from the company Wikia contacted me and said, ‘This is cool that you have a Plan B for Yahoo.’ I had put up a seven-point plan on my blog and invited people to comment or criticize it or add to it. I was hoping it would further engage people in the group. They would feel they were part of the process and other people would have better ideas than me, too. That’s one of the tenents of Web 2.0, that the group is smarter than any individual.

So the people from Wikia said, ‘We could set up a wiki for you and people could more easily edit that.’ So we added that to the mix a few weeks later, and someone from a company called YouChoose.net contacted me. They encourage people who want to start a petition or cause to go to the site and get people to join their cause. They said they could help me create a widget for my site so people who want to join the cause could put in their information, say how many Yahoo shares they own, and it would instantly go into this graph showing support over time.

All those things were novel and added to the campaign. Immediately we had 25 people pledge with 50,000 Yahoo shares to the group in the first week. And the New York Times, Dow Jones and Red Herring wrote articles about it. It was a virtuous circle where someone would write about it in the press, and then people would go to the site and pledge shares, and then after more people signed up, the press would write more about it. It slowly built up over the coming weeks.

How did you know that these people really were Yahoo shareholders? Did you verify it in some way?

Jackson: It’s an honor system, but we follow-up with them later to verify. We have had bogus pledges in the past. Usually, they’re easy to spot because they have a very high number of shares and have a funny name for the pledger. In those cases, we follow-up with them by email and ask them to verify it. If they don’t respond, we delete their pledge.

We ask them for name, full contact info, shares owned, when purchased, etc. We haven’t made them sign legal docs or ask them to send us photocopies of shares. We simply put the detailed list together and receive verification from them that they represent that they truly own their shares.

Were the Web 2.0 things actually working at spreading the word or were they just helping in getting attention in the press?

Jackson: I had the feeling through the whole campaign and even now, I really feel it’s so early days with this. I really believe in five years, activism will happen almost exclusively over the Internet. There will be forum groups and not just Yahoo Finance boards where people complain and say, ‘The people who run companies are bums.’ They will really exchange ideas with video messages and people will become more sophisticated as individual shareholders.

Did it matter? Yes it mattered, but we just got glimpses about how much it could matter. When I first put the Yahoo Plan B on the wiki we didn’t get many comments. It had been up on my blog before the wiki and people had left comments on the blog; some liked it and some criticized it.

Last fall, though, I did a wiki for a campaign with Motorola, and in that case I used the wiki right from the beginning and we got quite a few constructive comments on the wiki. So the tool was important, and it wasn’t just about having a nice story. There were some tools that were less valuable. The Facebook group, we could get people to join it, but there wasn’t much more they could do. We referred people from there to the blog, and it was a way for people to hear about us, but there wasn’t really an exchange of ideas there. That was an example of a tool that the press mentioned but it didn’t make that much of a difference.

You mentioned that the Yahoo campaign was the first case of individual investors making a big difference at a public company. Was that what happened last year with Terry Semel leaving the company?

Jackson: Yes, that’s what happened. There have always been activist investors at companies. They’re usually called gadflies, they are usually old ladies or old men who show up at annual shareholder meetings and shake their fists and cause a scene. At the end of the day they are only representing themselves so they are usually forgotten. This was the first time that an individual investor — not an institutional investor — assembled a group and voiced an opinion and had other people listen to it, and many people agreed with it and it definitely had an effect.

Leading up to the annual meeting in June last year, Yahoo did invite me to meet with them at their office. I did visit them and met with the general counsel, Michael Callahan, and a couple people who worked for him. I was hoping it would be this meeting where they might agree with two of our nine points, and we could be really happy. But it turned out, they were very cordial, and they just listened to me presenting our positions. But they didn’t really do anything afterwards.

Because of that non-action, I encouraged other shareholders to vote against board members at the annual shareholder meeting in June. They have a rule that if any one director got less than 50% support from shareholders, they would have to resign. So my hope was that if we got a substantial ‘no’ vote then Yahoo would have to listen to that as a big sign of shareholder dissatisfaction. So I spoke out, and was interviewed in the press because I spoke out, and I created a couple YouTube videos that I modeled after negative political campaign ads, saying why you should vote ‘no’ on a proposition or against someone. They were half-humorous but effectively delivered the message.

All the big institutions would say to me, ‘Listen Eric, we’re not going to join your group because we don’t do that, but we think what you’re doing is great, we’re making similar points ourselves to the Yahoo management, so keep their feet to the fire!’ At the annual meeting, there was a large ‘against’ vote. Some of the directors got 33% or 35% against votes, which is quite high for those types of votes. We were effective as an individual shareholder group, because we voiced a strong opinion and did it in a professional way. It wasn’t in a way that people could dismiss as crazy, ‘Oh don’t pay any attention to them.’ Our group did get 2.1 million shares pledged to our group, which is a lot but still was only 0.2% of total Yahoo shares outstanding.

When doing a campaign like this, if you don’t have the financial muscle, I guess the media exposure is really important.

Jackson: For sure. The media exposure was as important as the actual people who supported the campaign. In the days leading up to the annual meeting, a lot of press people were writing stories or doing TV pieces in anticipation of the meeting. And everyone in the pre

This is really inspiring. Maybe there will be a campaign like this to protest the issues associated with the corporatization of the media.

This is really inspiring. Maybe one day there can be a similar campaign to protest the issues caused by the corporatization of the media.