Like many of you, I embrace the guide-on-the-side model for teaching vs. the sage-on-the-stage version. That’s why each spring, about five weeks into the semester, my Writing and Editing for Convergent Media course at American University transforms from a classroom into a newsroom, complete with assigned roles, Google spreadsheets, closed Facebook groups and ethical issues to tackle.

The deliverable? A multimedia journalism project – conceived, edited, produced, designed, shot and pushed out by the students – produced for a media partner. We’ve collected six years of projects – from an emotional exploration of the impact of 9/11 on students their age, to the powerful recollections of millennial veterans returning to college.

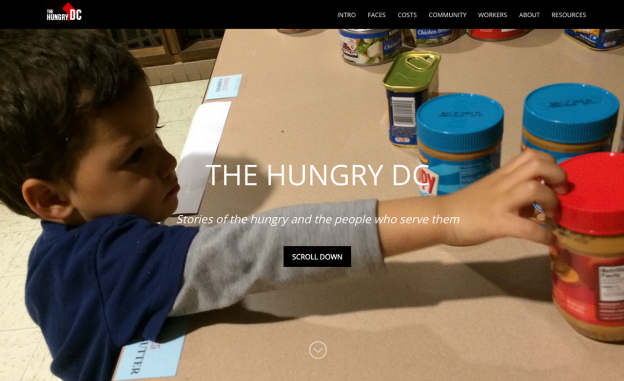

In spring, 2014, my students decided to tackle the topic of hunger in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area, one of our most complex topics to date. It is called The Hungry DC and was produced in partnership with WAMU.org at American University.

Supervising the class project for half a dozen years has taught me a lot. There are the variables, of course: student interests and technology change constantly. I also don’t know who will enroll in the course. Some projects have stronger video or better design or top-notch interactive graphics because the final projects are based on the skill sets walking in.

But this is a given: Students, many of whom are about to graduate, want something important to show off, are extremely proud of running their own show and are harder on each other’s content than you’d imagine. They also bring to the table everything they’ve learned from your colleagues, whose names pop up during class discussions in a charmingly spontaneous way.

9 Steps to Transforming your Classroom

Here is our step-by-step guide. It may not work for your classroom exactly, but you can modify as you need if you’d like to try this kind of project.

1. Select your topic wisely, allowing students to debate online and vote in person. Throughout the year, I stockpile a few ideas. I lean toward topics that are important to the lives of people roughly 20 to 24 years old. Two rules: the topic needs a peg or timeliness, and students have to report in the metro area. This year the students debated topics on our Blackboard forum – from a look at transgender issues on campus to cyber-privacy – before settling on the issue of hunger. There was a policy peg, not to mention a still-challenged economy.

2. Find a media partner. In the past, the class has partnered with Gannett, The Washington Post and WAMU.org. Once the partnership is established, we hammer out introductions to be used while interviewing, so sources know this project will not only be published, but likely published on the partner’s site.

3. Determine student roles early. We distribute job descriptions in the first few weeks of class. Students check off their top three choices and explain why. Positions include research chief (for fact checking) and social media editor along with managing editor, assigning editor, web designer, video editor, graphics editor and copy chief. I add or subtract titles based on individual strengths or interests. Each student, except the managing editor, also reports a story — in any format.

4. Select a great leadership team. I have been super lucky to have wonderful classroom leaders who self-identified. It is fun to watch the project bend to their personalities and interests. Once all the roles are established, students set the deadlines, tone, style, look and guidelines. They create a spreadsheet to track content. I meet with leadership once a week.

5. Create a closed Facebook group for the project. This is where all the action takes place and where students have been most comfortable sharing links, tips, admonitions, warnings, deadlines and generally staying in touch collectively.

6. Line up “experts.” Once the partnership is set, we invite the media liaison to the classroom to brainstorm. We also invite student leaders from earlier projects. And we bring in topic experts for on-the-record informational sessions. One year, it was the campus veteran services coordinator; this year we brought in an organizer from the area’s largest food bank.

7. If possible, partner with a communication research class. In previous years, we were lucky to work with Professor Maria Ivancin, who led the students in conducting an accompanying survey. We still marvel at how prescient the students were.

8. Give the project breathing room and reporting days. Students have jobs, internships and a host of other classes. They need days off to report, shoot and edit.

9. Recognize a quarter of the stories might not work. You’ll find some need to be rewritten, re-assigned, or re-reported. Just like life! I try to make sure each student has a success, if possible.

This year, hunger was a challenging topic because it took students out of their comfort zone, and they grappled with a variety of challenges summed up loosely — “If a reporter is privileged, can he or she understand this reality?” “Should we call someone hungry or food insecure?” We had a colleague, a law and ethics expert, on standby for the inevitable questions that arose. In addition, a former student came back to help us tackle WordPress fussiness. Other professors or friends stopped by to respond to needs on demand.

The Big Reveal

Then something happens at the end of each semester that blows me away. This year it happened again, with a vengeance. In the week between the last class and the project presentation, students on their own stream into the empty classroom or a nearby lab to produce and massage their project. On their study day. Late at night. Sometimes until morning. They wanted the site to be good, accurate, navigable, clear — thanks to the leadership of graduate student Hoai-Tran Bui.

Sure, the inevitable second-guessing occurs after publication. This is school, after all. And I made some mistakes; I didn’t leave enough class time for production, for example.

But as they rush to deadline, the students know this is their work, beginning to end. (Note: I read and comment on all the content before it is posted; students factor that into the workflow. Sometimes I allow them to overrule me.)

Kendall Breitman, newly graduated and now a reporter at Politico, reflects on why the project ownership is key.

“At first it was hard to balance the fact that the people you’re working with are your peers,” she writes in an email. “But at the same time there was a hierarchy to the roles that people played in the project. Especially since most of us are so used to being interns, taking on a higher role was awkward in that way.”

But Breitman says the most important aspect of this format was “working with my classmates.” I know they would agree. In exit comments sent after publication, they pointed to team work as one of their top takeaways.

Amy Eisman is director of the master’s in media entrepreneurship and the weekend master’s in interactive journalism in the School of Communication at American University. Eisman previously was with Gannett, first at USA TODAY and later as executive editor of USA WEEKEND. Eisman was also a managing editor at AOL and a Fulbright lecturer in Moscow. An early adopter of online education, she co-authored online training modules for Gannett about breaking news online, interactivity and database journalism. She’s held web writing workshops at the washingtonpost.com, Freedom Forum, VOA and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty in Prague and Moscow.