The Washington Post is creating an algorithm to augment its fact checking of political speeches. How might it work? And do we want it to?

During the Republican primaries in 2011, Steven Ginsberg, national political editor for the Washington Post, was covering a Michele Bachmann speech in Iowa.

It was a small affair, not much more than 50 people. After Bachman finished, Ginsberg got on the phone with Cory Haik, the Post’s executive producer for Digital News. What he wanted to know was whether there was a way they could accelerate the fact-checking process for political speeches and bring it as close to real-time as possible?

“Yes,” Haik recalls saying, “because to me, the answer is always yes.”

Her idea was that with the increasing frequency with which people use their mobile phones to record events, there’s almost always audio or video of a speech. If you could get a recording, you could then transcribe it and run it against a database of a newsroom’s known facts. The goal would be to try to create a real-time fact-checking algorithm.

“I was thinking of Shazam and thinking of how Shazam does what it does,” Haik explains. “But a Shazam for truth.” Her reference is to the music discovery app that instantly tells you the name and artist of a song when you hold your phone to a speaker playing the music.

“Figuring out whether elected leaders are lying is one of the oldest and most vital aspects of journalism, and that remains unchanged,” says Ginsberg. “But being able to figure that out instantly and all over the place at the same time would be revolutionary.”

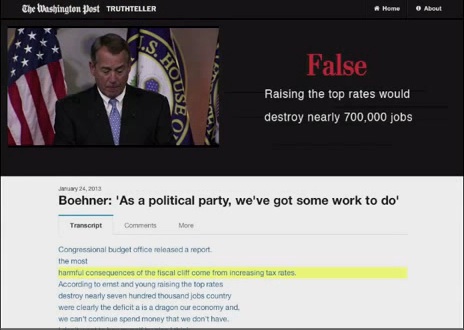

A $50,000 grant from the Knight Prototype Fund later and Ginsberg, Haik and their team have created Truth Teller, a prototype that is beginning to accomplish their goals.

How it Works

What the Post team has done at a high level is impressive. They can take a video, use speech-to-text to create a transcript, run that against a database they’ve created and start exploring facts — or fictions — as the case may be.

“Our algorithm goes through the transcript to find claims,” says Haik. “Then, whatever claims it sees in the text it touches our database and says, ‘OK, these claims match these facts,’ and this says it’s true or it’s false.”

The front end is a video with a transcript underneath it. Items considered facts are highlighted and the viewer can then select a “Fact Checks” tab to get the Post’s take on the veracity of a statement.

“Realistically, I think Truth Teller can be exactly what we’re aiming for, or very close to it,” writes Ginsberg in an e-mail to me. “Real-time fact-checking of political speeches will be possible. Getting there will require an enormous commitment and a great deal of effort, but it’s clear what needs to happen and we’re confident that we know how to make it happen.”

As a prototype, what’s shown is more promise and hope than the refinement of a finished product. As Haik explains to me on the phone, there’s still much to do.

“We have to tune the algorithm,” she says.

“We’ve got to build a database of facts that we put in ourselves,” she adds.

“We need to figure out how to structure the data across our site so we can touch that data in a good way,” she continues.

As Haik finishes this thought with, “We have to get the speech-to-text faster,” you can almost hear her clicking through a much longer mental checklist. Still, she believes they’ve developed a “real framework” to get to where they want to go.

Promise, Hope and Other Difficulties

Projects like these are difficult by their nature. Like those that try to measure sentiment across our social networks, there’s the difficulty of getting speaker intent from a straight transcript. For example, is the speaker being sarcastic, humorous or purposefully embellishing to drive home a larger point? Or what about literal versus figurative speech? As much as it annoys those of us outside the Washington circus, these are well-known tropes that people use to motivate and influence audiences. (Just to show two: Republicans want to starve the poor or Democrats want to make people dependent on government.)

And then, beyond the fib, there are all sorts of lies: some are white, some disassemble, some fabricate. There are the sins of omission, commission and exaggeration. Our vocabulary for lying is large and diverse because our ability to lie and otherwise shade the truth is large and diverse. The BBC even outlines which type of lies are journalistically relevant.

Add to this the “hard” and “soft” facts and the difficulty of the mission continues to grow. You can see a Truth Teller project working well with hard, numbers-driven realities since we already have companies like Narrative Science using algorithms to write sports, real estate and financial news. More difficult though is to take that algorithm and place it against soft, interpretative data — i.e. how sequestration will affect governmental agency X, Y or Z, if at all.

Natural Language Processing isn’t advanced enough, explains Damon Horowitz, Google’s in-house philosopher and professor, when I ask him what he conceptually thinks about a project like Truth Teller. The databases aren’t developed enough; we don’t have the right kind of information retrieval to do the matching (i.e., search); we don’t have the right kind of reasoning to make the inferences. We could derive simple systems that approximate the task, with high rates of errors. But the main issue here is that then you pay a lot of attention to those things which the system happens to be able to find, which is a curious way of advancing public debate.

Horowitz’s career straddles two interesting components: He’s created products and companies around the use of artificial intelligence and intelligent language processing, and he also happens to think about what this all means. Technically, we are a long way from being able to do a good job at the particular thing being proposed, he says.

So, yes, let’s agree that real-time fact-checking is a daunting task. But let’s also agree that we can set out our goals accordingly. Here, the idea isn’t trying to get the Machine to completely tell truth from fiction, but perhaps to provide a flag or warning system for humans to observe and dive into spoken “facts” more deeply.

“It’s important to understand that Truth Teller won’t replace fact-checkers,” Ginsberg says. “In fact, it relies on them, both to build and maintain the database and provide more information once lies are identified. The idea here isn’t to replace humans with robots, but to marry the best of old and new journalism.”

So How Might We Get There? And Still More Difficulties

No matter how large, a single newsroom can only do so much. It has only so much time and resources. For example, the Truth Teller team is manually entering facts into spreadsheets and its current set of facts is centered around taxes.

But what if a bunch of news organizations came together to create The Giant Database of Facts and augmented it, for example, with additional information from governmental agencies and trusted foundations and NGO’s? Plug in some APIs and perhaps you have something to work with.

Perhaps. Your base set of facts will be huge, but you can also see partisans decrying the facts to begin with (see, Climate Science, or last fall’s brouhaha over unemployment numbers during the election). That is, it’s easy to see arguments erupt over whose numbers are used, and who’s the gatekeeper to those numbers.

Culturally, you could see popular resistance to this type of system. People will always complain about “the media” and the perceived bias within it, but will they be comfortable with an automated, supposedly objective system put in its place?

Let me backtrack for just a bit: This article was motivated by a question posed to The Future Journalism Project on our Tumblr that runs like this:

Hi, I am a student in journalism and am preparing an article about robots (like the Washington Post’s Truth Teller) validating facts instead of journalists. I am curious to know the Future Journalism Project’s point of view of about this. What are the consequences for journalists, journalism and for democracy?

There’s a lot to unravel in the question and Horowitz identifies an inherent tension we have with accelerated technological change. We want it and we don’t want it.

“Socio-culturally, reactions to automation are always revealing,” he said. “On the one hand, there’s human desire for uniqueness, and a general conservatism and a dislike of change. On the other hand, there’s the dream of an automated future where we could escape the messiness of human affairs and doing things manually. There’s the hope that there is such a thing as a simple world of facts which could be exhaustively recorded, and the record could then be set straight.”

Haik, like Ginsberg, doesn’t think Truth Teller will replace human fact checkers, or interpret data and political statements. Instead, it’s an aid through the process.

If we keep it here, I think we have a tremendous tool for the newsroom. Consider it an early warning system that reporters, editors and the audience can all use. For example, the reporter files a story, submits it to Truth Teller and is alerted to possible errors or idiosyncrasies of fact. He or she can then go back to the data or the source to clarify or refine, or discover that the “fact on record” is, in fact, incorrect.

Obviously, this process can be repeated throughout the editorial workflow and speed the entire process. I’d argue the public should have access to something like the Truth Teller too — an interface through which they can drop articles and speeches to check on their own. Students and teachers have a system like this in TurnItIn, a plagiarism detection tool.

But technologies advance and soon we might see something quite different: an algorithmic truth-teller tracking our every step.

If it isn’t happening yet, it will sometime soon and the robots will be watching us.

Michael Cervieri is the creator of the Future Journalism Project. He has taught Internet and Mobile communication technologies at both the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and the university’s School of International and Public Affairs. On Twitter, he’s @bMunch. On Google+ he can be found here.

The Future Journalism Project is a multiplatform exploration of the present state, current disruption, and future possibilities of American journalism. Follow them on Twitter @The_FJP.

The Future Journalism Project is a multiplatform exploration of the present state, current disruption, and future possibilities of American journalism. Follow them on Twitter @The_FJP.